The optical Bloch equations

![{\displaystyle {\dot {\rho }}=-{\frac {i}{\hbar }}[H,\rho ]-{\frac {\Gamma }{2}}\left[{\sigma _{+}\sigma _{-}\rho -2\sigma _{-}\rho \sigma _{+}+\rho \sigma _{+}\sigma _{-}}\right]\,,}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/604d2158dbbebf16674738f973827dbb18e3a819)

provide a time-dependent quantum

description of a spontaneously emitting atom driven by a classical

electromagnetic field. Considerable insight into the physical

processes involved can be gained by studying these equations in the

transient excitation limit, as well as the steady-state limit, as we

see in this section. We begin by considering the coherent part of the

evolution, then extend this to re-visit the Bloch sphere picture of

the optical Bloch equations, which provides useful visualizations of

transient responses and steady state solutions. Finally, we return to vacuum Rabi oscillations and investigate how cavity loss leads to damping of the oscillations, as an illustration of master equations which are more general than the optical Bloch equation.

Eigenstates of the Jaynes-Cummings Hamiltonian

The Hamiltonian involved in the optical Bloch equations,

describes the evolution of an atom in a classical field.

We begin here by reviewing the coherent

evolution under  .

.

arises from the Jaynes-Cummings interaction we have previously

considered in the context of cavity QED, describing a single two-level

atom interacting with a single mode of the electromagnetic field:

arises from the Jaynes-Cummings interaction we have previously

considered in the context of cavity QED, describing a single two-level

atom interacting with a single mode of the electromagnetic field:

![{\displaystyle H_{JC}={\frac {\hbar \omega _{0}}{2}}\left[{|e\rangle \langle e|-|g\rangle \langle g|}\right]+\hbar \omega a^{\dagger }a+{\frac {\hbar \Omega }{2}}\left[{|g\rangle \langle e|+|e\rangle \langle g|}\right]\left[{a+a^{\dagger }}\right]\,.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/630609e3aab033690555f530c6e4323ba84a5538)

The last term in this expression is  , the dipole interaction

between atom and field. By defining

, the dipole interaction

between atom and field. By defining  and

and

, we may write this interaction as

, we may write this interaction as

![{\displaystyle H_{I}={\frac {\hbar \Omega }{2}}\left[{\sigma _{+}+\sigma _{-}}\right]\left[{a+a^{\dagger }}\right]\,.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/3410ceeb8ffe707f367fc599209a8dad817b08df)

In the frame of reference of the atom and field, recall that

When near resonance,  , and because the

, and because the

and

and  terms oscillate at nearly twice the frequency

of

terms oscillate at nearly twice the frequency

of  , those terms can be dropped. Doing so is known as the

rotating wave approximation, and it gives us a simplified

interaction Hamiltonian

, those terms can be dropped. Doing so is known as the

rotating wave approximation, and it gives us a simplified

interaction Hamiltonian

![{\displaystyle H_{I}={\frac {\hbar \Omega }{2}}\left[{a^{\dagger }\sigma _{-}+a\sigma _{+}}\right]\,.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/d60d32887d250fa22239d00c10278b510514772e)

Under this approximation, it is useful to note that this interaction

merely exchanges one quantum of excitation from atom to field, and

back, so that the total number of excitations  is a constant of the motion. We may thus write the total Hamiltonian,

in the rotating wave approximation, as

is a constant of the motion. We may thus write the total Hamiltonian,

in the rotating wave approximation, as

where we have defined  , and

, and  . Below, we may use

. Below, we may use  to simplify

writing.

to simplify

writing.

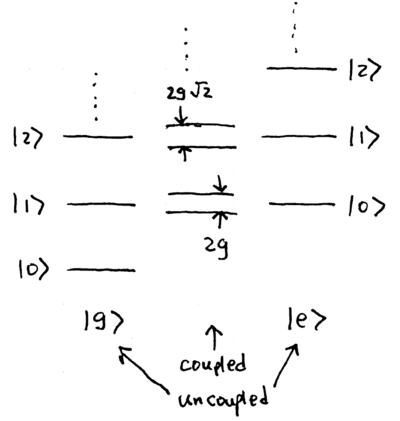

What are the eigenstates of this Hamiltonian? It describes a

two-level system coupled to a simple harmonic oscillator; when

uncoupled, if  , then the eigenstates are simply those of

, then the eigenstates are simply those of

,

,  and

and  , as shown here:

, as shown here:

When coupled, degenerate energy levels split (this is sometimes called dynamimc Stark splitting), with harmonic oscillator

levels  and

and  splitting into two energy levels separated

by

splitting into two energy levels separated

by  . Since the coupling only pairs levels separated by

one quantum of excitation, it is straightforward to show that the

eigenstates of the Jaynes-Cummings Hamiltonian fall into well defined

pairs of states, which we may label as

. Since the coupling only pairs levels separated by

one quantum of excitation, it is straightforward to show that the

eigenstates of the Jaynes-Cummings Hamiltonian fall into well defined

pairs of states, which we may label as  ; these are

; these are

![{\displaystyle |\pm ,n\rangle ={\frac {1}{\sqrt {2}}}\left[{|e,n\rangle \pm |g,n+1\rangle }\right]\,,}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/55f08b48a6a98c378c7ba35aff03487dd1c3463e)

and they have energies

When  , similar physics result, but with slightly more

complicated expressions describing the eigenstates, as we shall see

when we later return to the "dressed states" picture.

, similar physics result, but with slightly more

complicated expressions describing the eigenstates, as we shall see

when we later return to the "dressed states" picture.

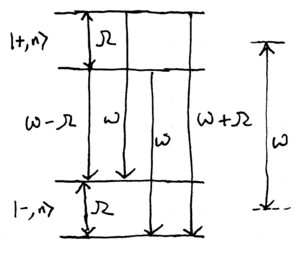

Strongly driven atom: Mollow triplet

An atom strongly coupled to a single mode electromagnetic field, or an

atom driven strongly by a single mode field, will thus have an

emission spectrum described by the coupled energy level diagram:

where, to good approximation, the energy level differences are

and

and  . These three lines which appear in the

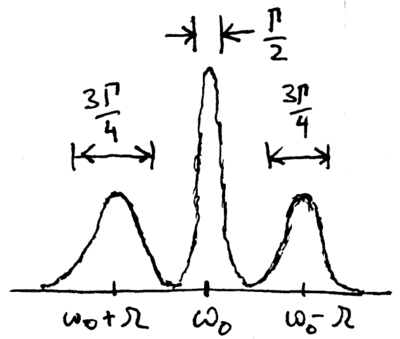

spectrum are known as the Mollow triplet:

. These three lines which appear in the

spectrum are known as the Mollow triplet:

The Mollow triplet is experimentally observed in a wide variety of

systems. However, while our energy eigenstate analysis has predicted

the number and frequencies of the emission lines, it fails to explain

a key characteristic: the widths are not the same. If the central

peak at  has width HWHM

has width HWHM  , the two sidebands each have a

HWHM of

, the two sidebands each have a

HWHM of  . To explain this, we need the optical Bloch

equations.

. To explain this, we need the optical Bloch

equations.

Optical Bloch equation evolution on the Bloch sphere

We have previously seen that an arbitrary qubit state  can be represented as being a

point on a unit sphere, located at

can be represented as being a

point on a unit sphere, located at  in polar

coordinates. Similarly, a density matrix

in polar

coordinates. Similarly, a density matrix  may be depicted as

being a point inside or on the unit sphere, using

may be depicted as

being a point inside or on the unit sphere, using

where  is the Bloch vector representation of

is the Bloch vector representation of  .

.

Explicitly, if we let

- Failed to parse (syntax error): {\displaystyle |0{\rangle}=|e{\rangle} = \left[ \begin{array}{cc}{1}\\{0}\end{array}\right], |1{\rangle}=|g{\rangle} = \left[ \begin{array}{cc}{0}\\{1}\end{array}\right], \\ \rho = \left[ \begin{array}{cc}{\rho_{ee}}&{\rho_{eg}}\\{\rho_{ge}}&{\rho_{gg}}\end{array}\right] \,, }

then

Which can be reversed to find

Visualization: Bloch vector

Visulization of the evolution of a density matrix under the optical

Bloch equations is thus helped by rewriting them in terms of a

differential equation for  . A convenient starting point for

this is the optical Bloch equation

. A convenient starting point for

this is the optical Bloch equation

![{\displaystyle {\dot {\rho }}=-{\frac {i}{\hbar }}[H,\rho ]-{\frac {\Gamma }{2}}\left[{\sigma _{+}\sigma _{-}\rho -2\sigma _{-}\rho \sigma _{+}+\rho \sigma _{+}\sigma _{-}}\right]\,,}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/604d2158dbbebf16674738f973827dbb18e3a819)

using the rotating frame Hamiltonian

This gives us the equations of motion

Note how these equations of motion provide a simple set of flows on

the Bloch sphere: the  terms correspond to a rotation in the

terms correspond to a rotation in the

plane,

plane,  corresponds to a rotation in the

corresponds to a rotation in the

plane, and

plane, and  drives a relaxation process

which shrinks

drives a relaxation process

which shrinks  and

and  components of the Bloch vector,

while moving the

components of the Bloch vector,

while moving the  component toward

component toward  .

.

Physics: in-phase and quadrature components

Physically, what is the meaning of  ,

,  , and

, and  ?

?  is

manifestly the population difference between the excited and ground

states. The other two components may be interpreted by recognizing

that the average dipole moment of the atom is

is

manifestly the population difference between the excited and ground

states. The other two components may be interpreted by recognizing

that the average dipole moment of the atom is

Thus,  and

and  correspond to the phase components of the atomic

dipole moment which are in-phase and in quadrature with the incident

electromagnetic field.

correspond to the phase components of the atomic

dipole moment which are in-phase and in quadrature with the incident

electromagnetic field.

Animation of full solutions

Here are plots of the full solutions of the optical Bloch equations on the Bloch sphere, for various cases of  ,

,  , and

, and  (sample matlab files to solve the differential equations: obefun1.m

plotobe2.m):

(sample matlab files to solve the differential equations: obefun1.m

plotobe2.m):

<jwplayer width="560" height="440" repeat="true" displayheight="420"

image="http://feynman.mit.edu/8.422/plotobe6.png"

autostart="false">http://feynman.mit.edu/8.422/plotobe6.flv</jwplayer>

Solutions of the optical Bloch equations

The optical Bloch equations, describing the evolution of a single atom coupled to the vacuum,

![{\displaystyle {\dot {\rho }}=-{\frac {i}{\hbar }}[H,\rho ]-{\frac {\Gamma }{2}}\left[{\sigma _{+}\sigma _{-}\rho -2\sigma _{-}\rho \sigma _{+}+\rho \sigma _{+}\sigma _{-}}\right]\,,}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/604d2158dbbebf16674738f973827dbb18e3a819)

are a set of three coupled differential equations,

written in the rotating frame of the atom's Hamiltonian. These equations can be solved analytically, but a great deal of intuition can be obtained from just studying the solutions in several limits. Here, we consider the steady state, transient, and weak excitation limits.

Transient response of the optical Bloch equations

The optical Bloch equations allow us to study the internal state of

the atom as it changes due to the external driving field, and due to

spontaneous emission.

Starting from the time-independent form of the equations,

we may note that when  and at resonance,

and at resonance,  ,

the Bloch vector exhibits pure damping behavior, towards

,

the Bloch vector exhibits pure damping behavior, towards  , and

, and

. Note that a convenient way to write these differential equations is in matrix form,

. Note that a convenient way to write these differential equations is in matrix form,

![{\displaystyle {\dot {\vec {r}}}=\left[{\begin{array}{ccc}{-\Gamma /2}&{-\delta }&{0}\\{\delta }&-\Gamma /2&-\Omega \\0&\Omega &-\Gamma \end{array}}\right]{\vec {r}}+\left[{\begin{array}{c}0\\0\\-\Gamma \end{array}}\right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/a0a21e6bfb27fa215b4628e5de75ae399517b2b7)

When  , Rabi oscillations occur, represnted by rapid

rotations of the Bloch vector about

, Rabi oscillations occur, represnted by rapid

rotations of the Bloch vector about  . Since the relaxation

along

. Since the relaxation

along  occurs at rate

occurs at rate  , and the relaxation about

, and the relaxation about

occurs at rate

occurs at rate  , we might expect that the average

relaxation rate of the rotating components under such a strong driving

field would be

, we might expect that the average

relaxation rate of the rotating components under such a strong driving

field would be  . The remaining

component

. The remaining

component  does not rotate, because it sits along

does not rotate, because it sits along  , the

axis of rotation. Thus, it relaxes with rate

, the

axis of rotation. Thus, it relaxes with rate  . Computation of the eigenvalues of the equations of motion verify this qualitative

picture, and show that for

. Computation of the eigenvalues of the equations of motion verify this qualitative

picture, and show that for  , and

, and  , the

eigenvalues of motion are

, the

eigenvalues of motion are  and

and  .

.

These

correspond to a main peak at  with width

with width  , and two

sidebands at

, and two

sidebands at  , with widths

, with widths  , thus

explaining the widths of the observed Mollow triplet lines.

, thus

explaining the widths of the observed Mollow triplet lines.

Steady-state solution of the optical Bloch equations

The steady state solution of the optical Bloch equations are found by

setting all the time derivatives to zero, giving a set of three

simultaneous equations,

Starting from the time-independent form of the equations,

The solutions are:

Physically, these are Lorentzians; the  solution (the component

in quadrature with the dipole) corresponds to an absorption curve with

half-width

solution (the component

in quadrature with the dipole) corresponds to an absorption curve with

half-width

and the  solution (the component in-phase with the dipole)

corresponds to a dispersion curve. And under a strong driving field,

as

solution (the component in-phase with the dipole)

corresponds to a dispersion curve. And under a strong driving field,

as  ,

,  , indicating that the

populations in the excited and ground states are equalizing. The

steady-state population in the excited state is

, indicating that the

populations in the excited and ground states are equalizing. The

steady-state population in the excited state is

an important result that will later be used in studying light forces.

These solutions can be re-expressed in a simplified manner by defining

the saturation parameter

in terms of which we find

As  , the atomic transitions become saturated, and the linewidth of the transition broadens from its

natural value

, the atomic transitions become saturated, and the linewidth of the transition broadens from its

natural value  , becoming

, becoming  on

resonance, at

on

resonance, at  .

.

Here are plots of the steady state solution for varying  :

:

<jwplayer width="560" height="440" repeat="true" displayheight="420"

image="http://feynman.mit.edu/8.422/steady4.png"

autostart="false">http://feynman.mit.edu/8.422/steady4.flv</jwplayer>

Weak excitation limit solution of the optical Bloch equations

Once again, the time-independent form of the optical Bloch equations is

where the remaining two components of the density matrix are given by

, and

, and  . It is

insightful to study these equations in the limit of weak excitation,

and for short evolution times.

. It is

insightful to study these equations in the limit of weak excitation,

and for short evolution times.

It turns out that the solution of these equations to lowest order

in  , and in the limit

, and in the limit  , with the initial

conditions

, with the initial

conditions  and

and  , gives

, gives

![{\displaystyle \rho _{ee}={\frac {{\frac {1}{4}}|\Omega |^{2}}{\delta ^{2}+\left({\frac {\Gamma }{2}}\right)^{2}}}\left[{1+e^{-\Gamma t}-2\cos(\delta t)e^{-\Gamma t/2}}\right]\,.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c19bf5cb1660757c54d1ccc65a9f0c4cbfcd57fe)

Moreover the solution of these equations to lowest order in

in the limit

in the limit  , with the initial conditions

, with the initial conditions  and

and  , gives

, gives

irrespective of the values of  and

and  .

.

Damped vacuum Rabi oscillations

The optical Bloch equations can be generalized to describe not just an

atom interacting with the vacuum, but also an atom and a single cavity

mode, each interacting with its own reservoir. This is the master

equation for cavity QED, and using such a master equation we can

revisit the phenomenon of vacuum Rabi oscillations and see what

happens in the presence of damping.

Generalization of the optical Bloch equations

The starting point for generalizing the optical Bloch equations is the

Lindblad form we previously saw in the

full-derivation walkthrough,

![{\displaystyle {\dot {\rho }}_{A}=-{\frac {i}{\hbar }}[H,\rho _{A}]-{\frac {\Gamma }{2}}\left[{\sigma _{+}\sigma _{-}\rho _{A}-2\sigma _{-}\rho _{A}\sigma _{+}+\rho _{A}\sigma _{+}\sigma _{-}}\right]\,.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/13bf26eb3d88c4444078e147d8e6751295dea1fd)

In this expression,  and

and  are "jump operators,"

and represent changes that occur to the atom when distinct dissipative

events happen ("distinct" meaning that the environment changes

between orthogonal states).

are "jump operators,"

and represent changes that occur to the atom when distinct dissipative

events happen ("distinct" meaning that the environment changes

between orthogonal states).

We may write the master equation for our more general scenario by

replacing the atomic density matrix  by a general density

matrix

by a general density

matrix  representing the atom and cavity field, and by replacing

the atomic jump operators with general jump operators

representing the atom and cavity field, and by replacing

the atomic jump operators with general jump operators  ,

,

![{\displaystyle {\dot {\rho }}=-{\frac {i}{\hbar }}[H,\rho ]+\sum _{k}\left[{L_{k}\rho L_{k}^{\dagger }-{\frac {1}{2}}(L_{k}^{\dagger }L_{k}\rho +\rho L_{k}^{\dagger }L_{k})}\right]\,.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/f41a3c9853e8923bf9cfd246f4affa45f6e6039a)

Note that the  include normalization factors which reflect their

probabilities of occurrence. In other words, for the atom + vacuum

model,

include normalization factors which reflect their

probabilities of occurrence. In other words, for the atom + vacuum

model,  .

.

Master equation for cavity QED system

For the cavity QED model, the atom and cavity field each have possible

jump operators. In general, the atom and cavity may both couple to a

thermal field with  average photons. In such a case, the jump

operators are

average photons. In such a case, the jump

operators are  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and

, where

, where  parameterizes the

spontaneous emission rate of the atom in free space, and

parameterizes the

spontaneous emission rate of the atom in free space, and  is

parameterizes the cavity

is

parameterizes the cavity  factor.

factor.

Experimentally, typically the

environment, the vacuum, is essentially at zero temperature, so

, in which case the only two relevant jump operators are

, in which case the only two relevant jump operators are

and

and  .

.

Damped vacuum Rabi oscillations

Vacuum Rabi oscillations, in the absence of damping, involve only two

states of the atom and cavity:  and

and  . When damping is

added, the

. When damping is

added, the  state must be included, since both the atom and

cavity states can decay and loose their quanta of energy. Moreover,

because only one quantum of excitation is involved in this system, we

can observe the essential physics by considering the case when

state must be included, since both the atom and

cavity states can decay and loose their quanta of energy. Moreover,

because only one quantum of excitation is involved in this system, we

can observe the essential physics by considering the case when

is zero (no spontaneous emission), but

is zero (no spontaneous emission), but  is nonzero

(the cavity is leaky). Let

is nonzero

(the cavity is leaky). Let  be the vacuum Rabi frequency,

and denote this three state space by

be the vacuum Rabi frequency,

and denote this three state space by  ,

,  , and

, and

. Written out explicitly in terms of the

. Written out explicitly in terms of the  density matrix elements

density matrix elements  , the master equation is (for the case

, the master equation is (for the case  with the system starting in the state

with the system starting in the state  )

)

When the cavity damping rate is small,  , then the

vacuum Rabi oscillations are damped, with average damping rate

, then the

vacuum Rabi oscillations are damped, with average damping rate

since the atoms spend roughly half their time in the excited state.

since the atoms spend roughly half their time in the excited state.

When the cavity damping rate is large,  , then the

atomic excitation is irreversibly damped, and no oscillations occur.

Let

, then the

atomic excitation is irreversibly damped, and no oscillations occur.

Let  be the probability of being in the

be the probability of being in the  state. We can combine two of the above equations to write

state. We can combine two of the above equations to write

Since in this case  , and

, and

, it follows that

, it follows that

Since in this regime, we slowly try to populate state  while it quickly decays away, we can approximate

while it quickly decays away, we can approximate  giving

giving

Finally plugging this back into the optical bloch equation for  yields

yields

so  decays exponentially, with rate

decays exponentially, with rate  .

Note that a large cavity damping rate slows down the decay of the atom's excited state. This is due to the fact that the stimulated transition (Rabi oscillation) to the lower state is slowed down by the cavity damping (which is a manifestation of the quantum Zeno effect).

.

Note that a large cavity damping rate slows down the decay of the atom's excited state. This is due to the fact that the stimulated transition (Rabi oscillation) to the lower state is slowed down by the cavity damping (which is a manifestation of the quantum Zeno effect).

Purcell factor: cavity enhanced spontaneous emission

How does this compare with the free space spontaneous emission rate

? Recall that the vacuum Rabi frequency is (for the case that the dipole matrix element vector and cavity mode polarization are aligned)

? Recall that the vacuum Rabi frequency is (for the case that the dipole matrix element vector and cavity mode polarization are aligned)

where  is the atomic dipole moment and

is the atomic dipole moment and  is the electric field

amplitude of a single photon at the atomic transition frequency

is the electric field

amplitude of a single photon at the atomic transition frequency

(Note that this is a standing wave in a cavity so it is a factor of two larger than the field for a running wave),

(Note that this is a standing wave in a cavity so it is a factor of two larger than the field for a running wave),

and  is the cavity volume. This gives

is the cavity volume. This gives

Letting  , we thus find that

, we thus find that

as the decay rate of the atom in the cavity.

Recall that the spontaneous emission rate of an atom in free space, as

determined by Fermi's golden rule, is

The ratio of this rate to the decay rate in the cavity is

where we take  as being the wavelength of

the cavity field, which is assumed to be resonant with the atomic

transition frequency

as being the wavelength of

the cavity field, which is assumed to be resonant with the atomic

transition frequency  . Note that

. Note that  is independent of the atomic dipole strength, and determined solely by

cavity parameters. Moreover, note that for small, high-

is independent of the atomic dipole strength, and determined solely by

cavity parameters. Moreover, note that for small, high- cavities, the decay rate of the atom in the

cavity can be much larger than the free space spontaneous emission

rate. This "cavity enhanced" spontaneous emission rate was predicted

by Purcell (1946), an observation credited as being the starting point

of cavity QED.

cavities, the decay rate of the atom in the

cavity can be much larger than the free space spontaneous emission

rate. This "cavity enhanced" spontaneous emission rate was predicted

by Purcell (1946), an observation credited as being the starting point

of cavity QED.

References

![{\displaystyle {\dot {\rho }}=-{\frac {i}{\hbar }}[H,\rho ]-{\frac {\Gamma }{2}}\left[{\sigma _{+}\sigma _{-}\rho -2\sigma _{-}\rho \sigma _{+}+\rho \sigma _{+}\sigma _{-}}\right]\,,}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/604d2158dbbebf16674738f973827dbb18e3a819)

![{\displaystyle H_{JC}={\frac {\hbar \omega _{0}}{2}}\left[{|e\rangle \langle e|-|g\rangle \langle g|}\right]+\hbar \omega a^{\dagger }a+{\frac {\hbar \Omega }{2}}\left[{|g\rangle \langle e|+|e\rangle \langle g|}\right]\left[{a+a^{\dagger }}\right]\,.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/630609e3aab033690555f530c6e4323ba84a5538)

![{\displaystyle H_{I}={\frac {\hbar \Omega }{2}}\left[{\sigma _{+}+\sigma _{-}}\right]\left[{a+a^{\dagger }}\right]\,.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/3410ceeb8ffe707f367fc599209a8dad817b08df)

![{\displaystyle H_{I}={\frac {\hbar \Omega }{2}}\left[{a^{\dagger }\sigma _{-}+a\sigma _{+}}\right]\,.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/d60d32887d250fa22239d00c10278b510514772e)

![{\displaystyle |\pm ,n\rangle ={\frac {1}{\sqrt {2}}}\left[{|e,n\rangle \pm |g,n+1\rangle }\right]\,,}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/55f08b48a6a98c378c7ba35aff03487dd1c3463e)

![{\displaystyle {\dot {\vec {r}}}=\left[{\begin{array}{ccc}{-\Gamma /2}&{-\delta }&{0}\\{\delta }&-\Gamma /2&-\Omega \\0&\Omega &-\Gamma \end{array}}\right]{\vec {r}}+\left[{\begin{array}{c}0\\0\\-\Gamma \end{array}}\right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/a0a21e6bfb27fa215b4628e5de75ae399517b2b7)

![{\displaystyle \rho _{ee}={\frac {{\frac {1}{4}}|\Omega |^{2}}{\delta ^{2}+\left({\frac {\Gamma }{2}}\right)^{2}}}\left[{1+e^{-\Gamma t}-2\cos(\delta t)e^{-\Gamma t/2}}\right]\,.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c19bf5cb1660757c54d1ccc65a9f0c4cbfcd57fe)

![{\displaystyle {\dot {\rho }}_{A}=-{\frac {i}{\hbar }}[H,\rho _{A}]-{\frac {\Gamma }{2}}\left[{\sigma _{+}\sigma _{-}\rho _{A}-2\sigma _{-}\rho _{A}\sigma _{+}+\rho _{A}\sigma _{+}\sigma _{-}}\right]\,.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/13bf26eb3d88c4444078e147d8e6751295dea1fd)

![{\displaystyle {\dot {\rho }}=-{\frac {i}{\hbar }}[H,\rho ]+\sum _{k}\left[{L_{k}\rho L_{k}^{\dagger }-{\frac {1}{2}}(L_{k}^{\dagger }L_{k}\rho +\rho L_{k}^{\dagger }L_{k})}\right]\,.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/f41a3c9853e8923bf9cfd246f4affa45f6e6039a)