Equation of Motion for the Expectation Value

For the system we have been considering, the Hamiltonian is

Recalling the Heisenberg equation of motion for any operator

is

is

![{\displaystyle {\frac {d}{dt}}{\hat {O}}={\frac {i}{\hbar }}\left[{\hat {H}},{\hat {O}}\right]+{\frac {\partial {\hat {O}}}{\partial t}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/ae5069cad777556e25ef2674f2ed7f1fbdc641a0)

where the last term refers to operators with an explicit time dependence, we

have in this instance

![{\displaystyle {\frac {d}{dt}}{\hat {\mu }}_{k}=\gamma {\frac {d}{dt}}{\hat {L}}_{k}={\frac {i\gamma }{\hbar }}\left[{\hat {H}},{\hat {L}}_{k}\right]=-{\frac {i\gamma ^{2}}{\hbar }}B_{0}\left[{\hat {L}}_{z},{\hat {L}}_{k}\right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/31c5220d2321caf92920986550a99c6ba69fb523)

Using ![{\displaystyle \left[{\hat {L}}_{k},{\hat {L}}_{l}\right]=i\hbar \epsilon _{klm}{\hat {L}}_{m}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/5b0dce00bc29fe901e80ab62151d3d46ed0adb58) with the

Levi-Civita symbol

with the

Levi-Civita symbol  , we have

, we have

or in short

These are just like the classical equations of motion

\ref{eq:classical_precession_in_static_field}, but here they describe the

precession of the operator for the magnetic moment  or for the

angular momentum

or for the

angular momentum  about the magnetic field at the (Larmor)

angular frequency

about the magnetic field at the (Larmor)

angular frequency  .

Note that

\begin{itemize}

\item

Just as in the classical model, these operator equations are

exact; we have not neglected any higher order terms.

\item

Since the equations of motion hold for the operator, they must hold for

the expectation value

.

Note that

\begin{itemize}

\item

Just as in the classical model, these operator equations are

exact; we have not neglected any higher order terms.

\item

Since the equations of motion hold for the operator, they must hold for

the expectation value

\item

We have not made use of any special relations for a spin- system, but

just the general commutation relation for angular momentum. Therefore the

result, precession about the magnetic field at the Larmor frequency, remains

true for any value of angular momentum

system, but

just the general commutation relation for angular momentum. Therefore the

result, precession about the magnetic field at the Larmor frequency, remains

true for any value of angular momentum  .

\item

A spin-

.

\item

A spin- system has two energy levels, and the two-level problem with

coupling between two levels can be mapped onto the problem for a spin in a

magnetic field, for which we have developed a good classical intuition.

\item

If coupling between two or more angular momenta or spins within an atom

results in an angular momentum

system has two energy levels, and the two-level problem with

coupling between two levels can be mapped onto the problem for a spin in a

magnetic field, for which we have developed a good classical intuition.

\item

If coupling between two or more angular momenta or spins within an atom

results in an angular momentum  , the time evolution of this angular

momentum in an external field is governed by the same physics as for the

two-level system. This is true as long as the applied magnetic field is not

large enough to break the coupling between the angular momenta; a situation

known as the Zeeman regime. Note that if the coupled angular momenta have

different gyromagnetic ratios, the gyromagnetic ratio for the composite angular

momentum is different from those of the constituents.

\item

For large magnetic field the interaction of the individual constituents

with the magnetic field dominates, and they precess separately

about the magnetic field. This is the Paschen-Back regime.

\item

An even more interesting composite angular momentum arises when

, the time evolution of this angular

momentum in an external field is governed by the same physics as for the

two-level system. This is true as long as the applied magnetic field is not

large enough to break the coupling between the angular momenta; a situation

known as the Zeeman regime. Note that if the coupled angular momenta have

different gyromagnetic ratios, the gyromagnetic ratio for the composite angular

momentum is different from those of the constituents.

\item

For large magnetic field the interaction of the individual constituents

with the magnetic field dominates, and they precess separately

about the magnetic field. This is the Paschen-Back regime.

\item

An even more interesting composite angular momentum arises when

two-level atoms are coupled symmetrically to an external

field. In this case we have an effective angular momentum

two-level atoms are coupled symmetrically to an external

field. In this case we have an effective angular momentum

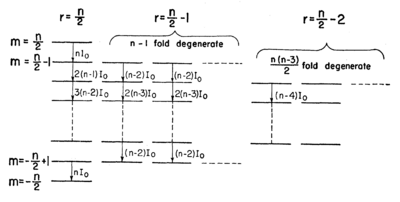

for the symmetric coupling (see Figure \ref{fig:dicke_states}).

\begin{figure}

for the symmetric coupling (see Figure \ref{fig:dicke_states}).

\begin{figure}

\caption{Level structure diagram for  two-level atoms in a basis of symmetric

states \cite{Dicke1954}. The leftmost column corresponds to an effective

spin-

two-level atoms in a basis of symmetric

states \cite{Dicke1954}. The leftmost column corresponds to an effective

spin- object. Other columns correspond to manifolds of symmetric states of

the

object. Other columns correspond to manifolds of symmetric states of

the  atoms with lower total effective angular momentum.}

atoms with lower total effective angular momentum.}

\end{figure}

Again the equation of motion for the composite angular momentum  is a precession. This is the problem considered in Dicke's famous paper

\cite{Dicke1954}, in which he shows that this collective precession can give

rise to massively enhanced couplings to external fields ("superradiance") due

to constructive interference between the individual atoms.

\end{itemize}

is a precession. This is the problem considered in Dicke's famous paper

\cite{Dicke1954}, in which he shows that this collective precession can give

rise to massively enhanced couplings to external fields ("superradiance") due

to constructive interference between the individual atoms.

\end{itemize}

The Two-Level System: Spin-1/2

Let us now specialize to the two-level system and calculate the time evolution

of the occupation probabilities for the two levels.

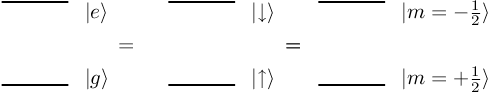

Equivalence of two-level system with spin- . Note that for

. Note that for

the spin-up state (spin aligned with field) is the ground state. For an electron, with

the spin-up state (spin aligned with field) is the ground state. For an electron, with  , spin-up is the excited state. Be careful, as both conventions are used in the literature.

, spin-up is the excited state. Be careful, as both conventions are used in the literature.

We have that

where in the last equation we have used the fact that  . The signs

are chosen for a spin with

. The signs

are chosen for a spin with  , such as a proton (Figure

\ref{fig:two_level_spin_half}). For an electron, or any other spin with

, such as a proton (Figure

\ref{fig:two_level_spin_half}). For an electron, or any other spin with

, the analysis would be the same but for the opposite sign of

, the analysis would be the same but for the opposite sign of  and the corresponding exchange of

and the corresponding exchange of  and

and  . If the system is

initially in the ground state,

. If the system is

initially in the ground state,  (or the spin along

(or the spin along

,

,  ), the expectation value obeys the classical

equation of motion \ref{eq:classical_rabi_flopping}:

), the expectation value obeys the classical

equation of motion \ref{eq:classical_rabi_flopping}:

Equation \ref{eqn:rabi_transition_probability} is the probability to find system

in the excited state at time  if it was in ground state at time

if it was in ground state at time  .

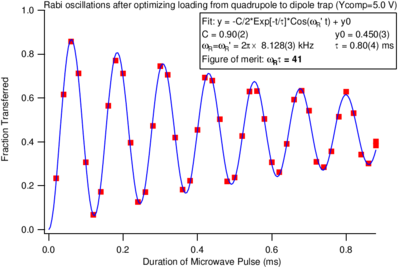

Figure \ref{fig:rabi_signal} shows a real-world example of such an oscillation.

.

Figure \ref{fig:rabi_signal} shows a real-world example of such an oscillation.

Rabi oscillation signal taken in the Vuleti\'{c} lab shortly after this

topic was covered in lecture in 2008. The amplitude of the oscillations decays

with time due to spatial variations in the strength of the drive field (and

hence of the Rabi frequency), so that the different atoms drift out of phase

with each other.

Matrix form of Hamiltonian

With the matrix representation

we can write the Hamiltonian  associated with the static

field

associated with the static

field  as

as

where  is the Larmor frequency, and

is the Larmor frequency, and

is a Pauli spin matrix. The eigenstates are  ,

,  with

eigenenergies

with

eigenenergies  . A spin initially

along

. A spin initially

along  , corresponding to

, corresponding to

evolves in time as

which describes a precession with angluar frequency  .

The field

.

The field  , rotating at

, rotating at  in the

in the  plane corresponds to

plane corresponds to

where have used the Pauli spin matrices  ,

,  . The full

Hamiltonian is thus given by

. The full

Hamiltonian is thus given by

This is the famous "dressed atom" Hamiltonian in the so-called "rotating wave

approximation". Its eigenstates and eigenvalues provide a very elegant, very

intuitive solution to the two-state problem.

Solution of the Schrodinger Equation for Spin-1/2 in the Interaction Representation

The interaction representation consists of expanding the state  in terms of the eigenstates

in terms of the eigenstates  ,

,  of the Hamiltonian

of the Hamiltonian  ,

including their known time dependence

,

including their known time dependence  due to

due to  .

That means we write here

.

That means we write here

Substituting this into the Schrodinger equation

then results in the equations of motion for the coefficients

Where we have used the matrix form of the Hamiltonian,

\ref{eq:dressed_atom_hamiltonian}. Introducing the detuning

, we have

, we have

The explicit time dependence can be eliminated by the sustitution

As you will show (or have shown) in the problem set, this leads to solutions for

given by

given by

with two constants that are determined by the initial conditions.

For  we find

we find

as already derived from the fact that the expectation value for

the magnetic moment obeys the classical equation.

Atomic Clocks and the Ramsey Method

When comparing the Hamiltonian for a spin- in a magnetic field to that of a

two-level system with a coupling between the two levels characterized by the

strength

in a magnetic field to that of a

two-level system with a coupling between the two levels characterized by the

strength  and frequency

and frequency  , we see that the energy spacing

between

, we see that the energy spacing

between  and

and  corresponds to the Larmor frequency

corresponds to the Larmor frequency  in the static field. This spacing can provide a frequency or time reference if

perturbations affecting

in the static field. This spacing can provide a frequency or time reference if

perturbations affecting  are sufficiently well controlled. For

instance, the time unit "second" is defined via the transition frequency

between two hyperfine states in the electronic ground state of the caesium atom,

which is near \unit{9.2}{\giga\hertz} in the microwave domain. The task of an

atomic clock is then to measure this frequency accurately by trying to tune a

frequency source (the frequency

are sufficiently well controlled. For

instance, the time unit "second" is defined via the transition frequency

between two hyperfine states in the electronic ground state of the caesium atom,

which is near \unit{9.2}{\giga\hertz} in the microwave domain. The task of an

atomic clock is then to measure this frequency accurately by trying to tune a

frequency source (the frequency  of the rotating field

of the rotating field  in the spin

picture) to the atomic frequency

in the spin

picture) to the atomic frequency  . Equivalently, we want to find the

frequency

. Equivalently, we want to find the

frequency  such that the detuning

such that the detuning  is equal to

zero.

Starting with an atom in

is equal to

zero.

Starting with an atom in  (spin along

(spin along  for

for

), we could try to find the resonance frequency by noting that

according to

), we could try to find the resonance frequency by noting that

according to

the population of the upper state is maximized for  (i.e. the

precession of the spin to the

(i.e. the

precession of the spin to the  direction is only complete on

resonance). This is the so-called Rabi method. It suffers from a number of

drawbacks. For one, the signal is only quadratic in the detuning

direction is only complete on

resonance). This is the so-called Rabi method. It suffers from a number of

drawbacks. For one, the signal is only quadratic in the detuning  , i.e.

the method is relatively insensitive near

, i.e.

the method is relatively insensitive near  . Furthermore, the optimum

time

. Furthermore, the optimum

time  depends on the strength

depends on the strength  of the coupling (i.e. the strength

of the coupling (i.e. the strength

of the rotating field), so fluctuations in

of the rotating field), so fluctuations in  can be mistaken for

changes in

can be mistaken for

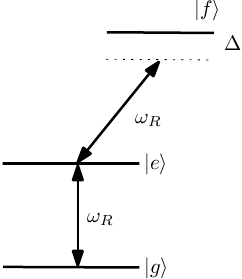

changes in  . Finally the coupling by

. Finally the coupling by  to other levels can

lead to level shifts that are not intrinsic to the atom, but depend on the

applied drive

to other levels can

lead to level shifts that are not intrinsic to the atom, but depend on the

applied drive  (Figure \ref{fig:rabi_third_level}).

\begin{figure}

(Figure \ref{fig:rabi_third_level}).

\begin{figure}

\caption{The drive used for Rabi flopping within the  ,

,  system can

also off-resonantly couple one or both levels to other states, perturbing the

transition frequency

system can

also off-resonantly couple one or both levels to other states, perturbing the

transition frequency  .}

.}

\end{figure}

Norman Ramsey invented an alternative method (the so-called "separated

oscillatory fields method", known for short as the "Ramsey method"

\cite{Ramsey1949,Ramsey1950}, for which he received the Nobel prize), that fixes

all of these problems. It leads to a signal that is linear rather than quadratic

in the detuning  , does not require tuning the measurement time to match

the applied field strength

, does not require tuning the measurement time to match

the applied field strength  , and, most importantly,

eliminates level shifts due to

, and, most importantly,

eliminates level shifts due to  altogether.

The method is as follows. Instead of applying a pulse for a time t that

corresponds to Rabi rotation of the spin by

altogether.

The method is as follows. Instead of applying a pulse for a time t that

corresponds to Rabi rotation of the spin by  (called a

(called a  pulse), the

pulse is applied for half that time, corresponding to the Rabi rotation of the

spin by

pulse), the

pulse is applied for half that time, corresponding to the Rabi rotation of the

spin by  into the

into the  plane (

plane ( pulse). Then the applied field

pulse). Then the applied field

is turned off and the system is left to precess in the static field

is turned off and the system is left to precess in the static field  (or at its natural frequency

(or at its natural frequency  ) for a measurement time

) for a measurement time  . Finally, a

second

. Finally, a

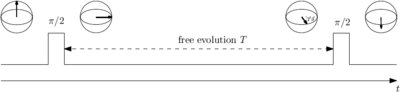

second  pulse, identical to the original one, is applied (see Figure

\ref{fig:ramsey_sequence}).

\begin{figure}

pulse, identical to the original one, is applied (see Figure

\ref{fig:ramsey_sequence}).

\begin{figure}

\caption{Ramsey sequence}

\end{figure}

The signal is the  component of the spin after the second

interaction. The signal after the second

component of the spin after the second

interaction. The signal after the second  pulse is an oscillating signal

in

pulse is an oscillating signal

in  , depending on how much phase the spin has acquired relative to the

local oscillator (the microwave signal generator at frequency

, depending on how much phase the spin has acquired relative to the

local oscillator (the microwave signal generator at frequency  ).

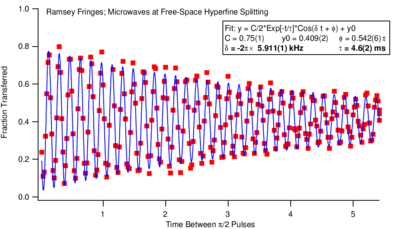

Examples of such curves are shown in Figures \ref{fig:ramsey_signal} and

\ref{fig:ramsey_vs_freq}.

\begin{figure}

).

Examples of such curves are shown in Figures \ref{fig:ramsey_signal} and

\ref{fig:ramsey_vs_freq}.

\begin{figure}

\caption{Ramsey oscillation signal as a function of time taken in the

Vuleti\'{c} lab in 2007. The drive field was deliberately detuned from

resonance so that the oscillation at the detuning frequency would be visible.}

\end{figure}

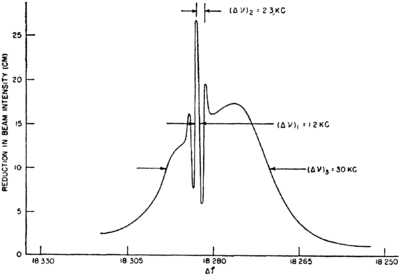

\begin{figure}

\caption{Experimental data from Ramsey's original paper \cite{Ramsey1950},

showing the signal as a function of frequency. Note the narrow oscillation,

whose width is set by the measurement time  , superimposed on the much broader

background set up by the inhomogeneously broadened

, superimposed on the much broader

background set up by the inhomogeneously broadened  pulses.}

pulses.}

\end{figure}

At the zero crossings we have maximum sensitivity of the signal with respect to

frequency changes. Note that the signal as a function of  looks similar to

Rabi flopping. However, there the zero crossing measure the Rabi frequency, not

looks similar to

Rabi flopping. However, there the zero crossing measure the Rabi frequency, not

.

.

![{\displaystyle {\frac {d}{dt}}{\hat {O}}={\frac {i}{\hbar }}\left[{\hat {H}},{\hat {O}}\right]+{\frac {\partial {\hat {O}}}{\partial t}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/ae5069cad777556e25ef2674f2ed7f1fbdc641a0)

![{\displaystyle {\frac {d}{dt}}{\hat {\mu }}_{k}=\gamma {\frac {d}{dt}}{\hat {L}}_{k}={\frac {i\gamma }{\hbar }}\left[{\hat {H}},{\hat {L}}_{k}\right]=-{\frac {i\gamma ^{2}}{\hbar }}B_{0}\left[{\hat {L}}_{z},{\hat {L}}_{k}\right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/31c5220d2321caf92920986550a99c6ba69fb523)

![{\displaystyle \left[{\hat {L}}_{k},{\hat {L}}_{l}\right]=i\hbar \epsilon _{klm}{\hat {L}}_{m}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/5b0dce00bc29fe901e80ab62151d3d46ed0adb58)