Now, unlike in classical mechanics, most resonances studied in atomic physics

are not harmonic oscillators, but two-level systems. Unlike harmonic

oscillators, two-level systems show saturation. When a harmonic oscillator is

driven longer or faster, higher and higher excited states are populated: the

oscillator amplitude can become arbitrarily large. In contrast, the amplitude

of oscillation in a two-level system is limited to one half in the appropriate

dimensionless units.\footnote{An analogous dimensionless amplitude for the

harmonic oscillator would be the amplitude measured in units of the oscillator

ground state size.}

Why, and under what conditions, do classical harmonic oscillator models of a

two-level system work? A two-level system of energy difference  can be

approximated by a harmonic oscillator of frequency

can be

approximated by a harmonic oscillator of frequency  when saturation effects in the two-level system are negligible, i.e. when the

population of the second excited state in the harmonic oscillator problem is

negligible, or equivalently when the population ratio of the first excited state

to the the ground state is small:

when saturation effects in the two-level system are negligible, i.e. when the

population of the second excited state in the harmonic oscillator problem is

negligible, or equivalently when the population ratio of the first excited state

to the the ground state is small:  . This is the basis for

the classical Lorentz model of the electron bound in the atom that describes

many linear atomic properties (for instance the refractive index) very well.

See "The origin of the refractive index" in chapter 31 of the Feynman

Lectures on Physics \cite{Feynman1963}.

When saturation comes into play, i.e. when the initial ground state is

appreciably depleted, the harmonic oscillator ceases to be a good model. The

limit on the oscillation amplitude in a two-level system suggests that a

classical system with periodic evolution and a limit on the amplitude, namely

rotation, could provide a better classical model of a two-level system. Indeed,

the motion of a classical magnetic moment in a uniform field provides a model

that captures almost all features of the quantum-mechanical two-level system,

the exception beting the projection onto one of the two possible outcomes in a

measurement.

\section{Magnetic Resonance: The Classical Magnetic Moment in a Spatially

Uniform Field}

. This is the basis for

the classical Lorentz model of the electron bound in the atom that describes

many linear atomic properties (for instance the refractive index) very well.

See "The origin of the refractive index" in chapter 31 of the Feynman

Lectures on Physics \cite{Feynman1963}.

When saturation comes into play, i.e. when the initial ground state is

appreciably depleted, the harmonic oscillator ceases to be a good model. The

limit on the oscillation amplitude in a two-level system suggests that a

classical system with periodic evolution and a limit on the amplitude, namely

rotation, could provide a better classical model of a two-level system. Indeed,

the motion of a classical magnetic moment in a uniform field provides a model

that captures almost all features of the quantum-mechanical two-level system,

the exception beting the projection onto one of the two possible outcomes in a

measurement.

\section{Magnetic Resonance: The Classical Magnetic Moment in a Spatially

Uniform Field}

Magnetic Moment in a Static Field

The interaction energy of a magnetic moment  with a magnetic field

with a magnetic field

is given by

is given by

In a uniform field the force

vanishes, but the torque

does not. For an angular momentum  the equation of motion is then

the equation of motion is then

where we have introduced the gyromagnetic ratio  as the proportionality

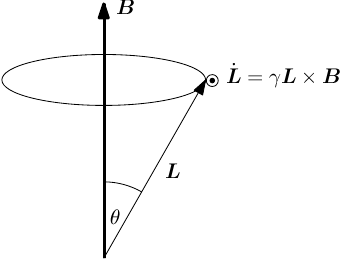

constant between angular momentum and magnetic moment, as shown in Figure

\ref{fig:static_precession}.

\begin{figure}

as the proportionality

constant between angular momentum and magnetic moment, as shown in Figure

\ref{fig:static_precession}.

\begin{figure}

\caption{Precession of a the magnetic moment and associated angular momentum

about a static field  .}

.}

\end{figure}

This describes the precession of the magnetic moment about the magnetic field

with angular frequency

is known as the Larmor frequency.

For electrons we have Failed to parse (unknown function "\unit"): {\displaystyle \gamma_e=2\pi\times\unit{2.8}{\mega\hertz\per G}}

,

for protons Failed to parse (unknown function "\unit"): {\displaystyle \gamma_e=2\pi\times\unit{4.2}{\kilo\hertz\per G}}

.

is known as the Larmor frequency.

For electrons we have Failed to parse (unknown function "\unit"): {\displaystyle \gamma_e=2\pi\times\unit{2.8}{\mega\hertz\per G}}

,

for protons Failed to parse (unknown function "\unit"): {\displaystyle \gamma_e=2\pi\times\unit{4.2}{\kilo\hertz\per G}}

.

An Alternative Solution: Rotating Coordinate System

A vector  rotating at constant angular velocity

rotating at constant angular velocity  is

described by

is

described by

Then the rates of change of  measured in a coordinate system rotating

at

measured in a coordinate system rotating

at  and in an inertial system are related by

and in an inertial system are related by

This follows immediately from the following facts:

\begin{itemize}

* If  is constant in the rotating system then

is constant in the rotating system then

.

.

* If  then

then

.

.

* Coordinate rotation is a linear transformation.

\end{itemize}

This transformation is sometimes abbreviated as the schematic rule

It follows that the angular momentum

in a rotating frame obeys

If we choose  , then

, then

is constant in the rotating frame. Often it is useful to

think of a fictitious magnetic field

is constant in the rotating frame. Often it is useful to

think of a fictitious magnetic field  that appears in a rotating frame.

that appears in a rotating frame.

Larmor's Theorem for a Charged Particle in a Magnetic Field

The vanishing of the torque on a magnetic moment when viewed in the correct

rotating frame is reminiscent of Larmor's theorm for the motion of a charged

particle in a magnetic field, which we now present.

If the Lorentz force acts in an inertial frame,

then in the rotating frame, according to the rule

\ref{eqn:rot_frame_transformation} we have

resulting in a force  in the rotating frame given by

in the rotating frame given by

where we have used

.

Choosing

.

Choosing

yields

if the  field is not too large. Thus the Lorentz force approximately

disappears in the rotating frame. Note that while the vanishing of the force is

approximate, the vanishing of the torque on a magnetic moment in the rotating

frame is an exact result.

field is not too large. Thus the Lorentz force approximately

disappears in the rotating frame. Note that while the vanishing of the force is

approximate, the vanishing of the torque on a magnetic moment in the rotating

frame is an exact result.

Rotating Magnetic Field on Resonance

\begin{figure}

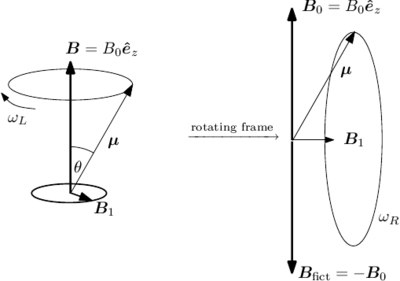

\caption{Field and moment vectors in the static and rotating frames for the case

of resonant drive.}

\end{figure}

Consider a magnetic moment  precessing about a field

precessing about a field

with

with  in spherical coordinates, where

in spherical coordinates, where  . Assume that we now

apply an additional field

. Assume that we now

apply an additional field  , in the

, in the  -plane rotating at

-plane rotating at

. To solve the resulting problem it is simplest to go into the

rotating frame (Figure \ref{fig:rotating_frame}). Then

. To solve the resulting problem it is simplest to go into the

rotating frame (Figure \ref{fig:rotating_frame}). Then  is

stationary, say along

is

stationary, say along  , and there is an additional fictitious

field

, and there is an additional fictitious

field  which

cancels the field

which

cancels the field  . So in the rotating frame we are left just with

the static field

. So in the rotating frame we are left just with

the static field  , and the magnetic moment precesses about

, and the magnetic moment precesses about

at the Rabi frequency

at the Rabi frequency

A magnetic moment initially along the  axis will point along

the

axis will point along

the  axis at a time

axis at a time  given by

given by  , while a

magnetic moment parallel or antiparallel to applied magnetic field

, while a

magnetic moment parallel or antiparallel to applied magnetic field  does not precess in the rotating frame.

\QU{

Assume the magnetic moment is initially pointing

along the

does not precess in the rotating frame.

\QU{

Assume the magnetic moment is initially pointing

along the  axis. Assume that a rotating field

axis. Assume that a rotating field  is

applied, but that it rotates at a frequency

is

applied, but that it rotates at a frequency  ,

where

,

where  is the Larmor frequency for the static field

is the Larmor frequency for the static field  .

Compared to the on-resonant case,

.

Compared to the on-resonant case,  , is the oscillation frequency of

the magnetic moment.

\begin{enumerate}

, is the oscillation frequency of

the magnetic moment.

\begin{enumerate}

* larger

* the same

* smaller

\end{enumerate}

}

\QU{

Same question as \ref{q:rabi_freq_blue_detuned} but for  .

}

.

}

Rotating Magnetic Field Off-Resonance

If the rotation frequency

of

of  does not equal the Larmor frequency

does not equal the Larmor frequency

associated with the static field

associated with the static field  , then in

the frame rotating with

, then in

the frame rotating with  at frequency

at frequency  the static field

is not completely cancelled by the fictitious field

the static field

is not completely cancelled by the fictitious field

, but a difference along

, but a difference along  remains,

giving rise to a total effective field in the rotating frame

remains,

giving rise to a total effective field in the rotating frame

The effective field is static, lies at an angle  with the z

with the z

and is of magnitude

The magnetic moment precesses around it with an effective (sometimes called

generalized) Rabi frequency

where  is the Rabi frequency associated with

is the Rabi frequency associated with  , and

, and

is the detuning from resonance with the Larmor

frequency

is the detuning from resonance with the Larmor

frequency  .

\subsection{Geometrical Solution for the Classical Magnetic Moment in Static and

Rotating Fields}

\begin{figure}

.

\subsection{Geometrical Solution for the Classical Magnetic Moment in Static and

Rotating Fields}

\begin{figure}

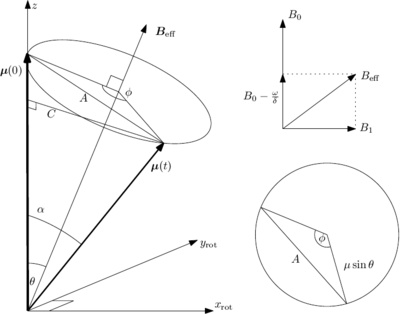

\caption{Geometrical relations for the spin in combined static and rotating

magnetic fields, viewed in the frame co-rotating with the drive field

. At lower right is a view looking straight down the

. At lower right is a view looking straight down the

axis.}

axis.}

\end{figure}

Referring to Figure \ref{fig:rotating_coord_construction}, we have

On the other hand

so that

With  the Larmor frequency of the static field,

the Larmor frequency of the static field,

the detuning,

the detuning,  the resonant and

the resonant and

the generalized Rabi frequencies. Note

that the precession is faster, but the amplitude smaller for an off-resonant

field than for the resonant case. The above result is also the correct

quantum-mechanical result.

the generalized Rabi frequencies. Note

that the precession is faster, but the amplitude smaller for an off-resonant

field than for the resonant case. The above result is also the correct

quantum-mechanical result.

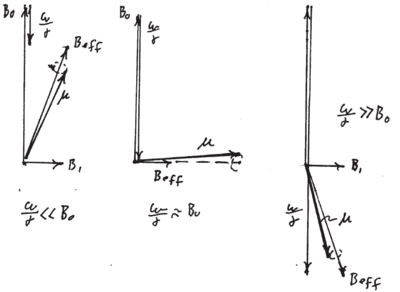

"Rapid" Adiabiatic Passage

Rapid adiabatic passage is a technique for inverting a spin by (slowly) sweeping

the detuning of a drive field through resonance. "Slowly" means slowly

compared to the Larmor frequency  about the effective

static field in the rotating frame for all times. The physical picture is as

follows. Assume the detuning is initially negative (

about the effective

static field in the rotating frame for all times. The physical picture is as

follows. Assume the detuning is initially negative ( ,

,

). Since

). Since

the effective magnetic field initially points of a small angle

relative to the  axis. If the detuning is increased slowly

compared to the Larmor frequency, the spin will continue to

precess tightly around

axis. If the detuning is increased slowly

compared to the Larmor frequency, the spin will continue to

precess tightly around  , which for

, which for  points

along the x axis, and for

points

along the x axis, and for  along the

along the  axis

(see Figure \ref{fig:rapid_adiabatic_passage}).

\begin{figure}

axis

(see Figure \ref{fig:rapid_adiabatic_passage}).

\begin{figure}

\caption{Motion of the spin during rapid adiabatic passage, viewed in the frame

rotating with  . The spin's rapid precession locks it to the

direction of

. The spin's rapid precession locks it to the

direction of  and thus it is dragged through an angle

and thus it is dragged through an angle  as the frequency is swept through resonance.}

as the frequency is swept through resonance.}

\end{figure}

Thus the magnetic moment, starting out along  ,

ends up pointing along

,

ends up pointing along  . Note that in the

rotating frame

. Note that in the

rotating frame  remains always (almost) parallel to the

effective field

remains always (almost) parallel to the

effective field  .

A similar precess is used in magnetic traps for atoms, but there

.

A similar precess is used in magnetic traps for atoms, but there

is a real, spatially dependent field constant in time.

As the atom moves in this field, the fast precession of the

magnetic moment about the local field keeps its direction locked

to the local field, whose direction varies in the lab frame.

Returning to rapid adiabatic passage, since the generalized Rabi frequency is

smallest and equal to the resonant Rabi frequency

is a real, spatially dependent field constant in time.

As the atom moves in this field, the fast precession of the

magnetic moment about the local field keeps its direction locked

to the local field, whose direction varies in the lab frame.

Returning to rapid adiabatic passage, since the generalized Rabi frequency is

smallest and equal to the resonant Rabi frequency  at

at  , the

adiabatic requirement is most severe there, i.e. near

, the

adiabatic requirement is most severe there, i.e. near  .

Near

.

Near  we have, with

we have, with  ,

,

where the exclamation point in  indicates a requirement which

we impose. Consequently, if the evolution is to be adiabatic, we must have

indicates a requirement which

we impose. Consequently, if the evolution is to be adiabatic, we must have

.

This means that the change

.

This means that the change  of rotation frequency

of rotation frequency

per Rabi period

per Rabi period  ,

,

,

must be small compared to the Rabi frequency

,

must be small compared to the Rabi frequency  . The quantum mechanical

treatment yields a probability for non-adiabatic transition (probability for the

magnetic moment not following the magnetic field) given by

. The quantum mechanical

treatment yields a probability for non-adiabatic transition (probability for the

magnetic moment not following the magnetic field) given by

in agreement with the above qualitative discussion.