Introduction

Every radiative process described so far has involved a single

photon, whether it be a hyperfine transition in magnetic

resonance, optical excitation, or spontaneous emission. However, at higher power, when first-order perturbation theory breaks down,

processes can occur in which an atom simultaneously absorbs

two or more photons. Such multi-photon processes can lead to

ionization of atoms or dissociation of molecules in intense laser

fields, and phenomena such as free-to-free transitions in which

an electron absorbs successive quanta as it flies out from the

field of an atom.

Two-photon processes have become one of the standard tools in atomic physics

for exciting atoms to states whose energies are too high to

achieve with a single photon (e.g. Rydberg states) and also to states of the same

parity that would normally be inaccessible. In addition, a number

of ultra-high resolution (doppler-free) spectroscopic techniques are based on

two-photon processes. The ubiquitous phenomena of resonance fluorescence and Rayleigh scattering are also two-photon processes.

Our approach will be to use second-order

perturbation theory, extending the first order development used

in earlier chapters in a straightforward fashion. An alternative

approach involves solving the dynamical equations in the same

manner as we analyzed the two-level system. However, the

perturbation approach is appropriate in many cases, and is simpler

than the dynamical approach.

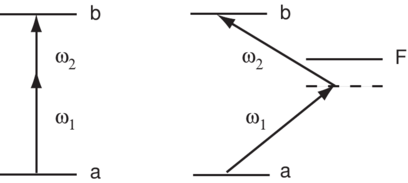

The aim is to cause a transition  by applying two

fields:

by applying two

fields:

where

States  and

and  have the same parity, so a

single photon transition is forbidden. The process is shown in

Fig.~\ref{fig:two-photon}, left. A more realistic view is shown in

Fig.~\ref{fig:two-photon} right, where

have the same parity, so a

single photon transition is forbidden. The process is shown in

Fig.~\ref{fig:two-photon}, left. A more realistic view is shown in

Fig.~\ref{fig:two-photon} right, where  represents some intermediate state of

opposite parity. One way to describe the process is that photon

represents some intermediate state of

opposite parity. One way to describe the process is that photon

causes a transition from

causes a transition from  to a "virtual"

state near

to a "virtual"

state near  and the second photon at

and the second photon at  carries the system from the virtual state to the final state

carries the system from the virtual state to the final state  . The interpretation of the virtual state will be discussed in Section \ref{sec:virtual}. Note that

. The interpretation of the virtual state will be discussed in Section \ref{sec:virtual}. Note that  , in reality,

represents one of a complete set of eigenstates which have non-vanishing dipole

matrix elements with

, in reality,

represents one of a complete set of eigenstates which have non-vanishing dipole

matrix elements with  .

.

Calculation of the Two-Photon Rate

The Hamiltonian is of the form  , where

, where

. With the field described by Eq.\

\ref{eq:introone},

we have

. With the field described by Eq.\

\ref{eq:introone},

we have

Defining

the matrix element  is

is

As the counterrotating terms are usually negligible, we have dropped them for simplicity.

Following the procedure used earlier, the first order solution for the

amplitude  of

of  is

is

![{\displaystyle a_{f}^{[1]}={\frac {1}{2i\hbar }}\int _{0}^{t}{\left[H_{fa,1}e^{-i(\omega _{1}-\omega _{fa})t^{\prime }}+H_{fa,2}e^{-i(\omega _{2}-\omega _{fa})t^{\prime }}\right]dt^{\prime }}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/38559b260418a7c9986c0a71053694d255fde10b)

![{\displaystyle ={\frac {1}{2\hbar }}{\left[{\frac {H_{fa,1}(e^{-i(\omega _{1}-\omega _{fa})t}-1)}{\omega _{1}-\omega _{fa}}}+{\frac {H_{fa,2}(e^{-i(\omega _{2}-\omega _{fa})t}-1)}{\omega _{2}-\omega _{fa}}}\right]}.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/935f78b88c94694c2a0cb19d4dde8d346f562860)

The second order solution for the  state amplitude,

state amplitude, ![{\displaystyle a_{b}^{[2]}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/278368d4b1e3e7e1f4784fa2317a18e367883f46) ,

is found from

,

is found from

![{\displaystyle i\hbar {\dot {a}}_{b}^{[2]}=\sum _{k}H_{bk}a_{k}^{[1]}e^{i\omega _{bk}.t}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/01e7c88170f91f6c7bd434f2a71b568f4af3c1d5)

The contribution to the sum due to state  is

is

![{\displaystyle a_{b}^{[2]}={\frac {1}{i\hbar }}\int _{0}^{t}\langle b|H|f\rangle e^{i\omega _{bf}t^{\prime }}a_{f}^{[1]}(t^{\prime })dt^{\prime }.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/94d7797523cd3b2b6baeefff4f653ee5338c84a5)

Introducing

and defining  , we have,

, we have,

\noindent

Eq.\ \ref{eq:ctprsix} yields

![{\displaystyle {\begin{array}{rcl}a_{b}^{[2]}&=&{\frac {1}{4\hbar ^{2}}}\sum _{f}\left[{\frac {H_{bf,1}H_{fa,1}}{\omega _{1}-\omega _{fa}}}{\frac {e^{i(\omega _{0}-2\omega _{1})t}-1}{\omega _{0}-2\omega _{1}}}+{\frac {H_{bf,2}H_{fa,2}}{\omega _{2}-\omega _{fa}}}{\frac {e^{i(\omega _{0}-2\omega _{2})t}-1}{\omega _{0}-2\omega _{2}}}\right.\\&&+\left.{\frac {H_{bf,2}H_{fa,1}}{\omega _{1}-\omega _{fa}}}{\frac {e^{i(\omega _{0}-\omega _{1}-\omega _{2})t}-1}{\omega _{0}-\omega _{1}-\omega _{2}}}+{\frac {H_{bf,1}H_{fa,2}}{\omega _{2}-\omega _{fa}}}{\frac {e^{i(\omega _{0}-\omega _{1}-\omega _{2})t}-1}{\omega _{0}-\omega _{1}-\omega _{2}}}\right].\end{array}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/0999100eb41b4ffa8b191e958e4850b550748bdb)

Note that the first two terms involve absorbing two photons from

the same beam, while the last two involve absorbing one photon

from each of the two beams. When two different frequencies are

used, the first terms are invariably far from resonance and can be

neglected. In the case of absorbing two photons at the same

frequency, discussed below, all four terms contribute.

\section{Two-photon rate with a single intermediate

state}

Suppose that  is close to

is close to  where

where  is a

particular intermediate state. In this case Eq.\ \ref{eq:ctprnine}

becomes

is a

particular intermediate state. In this case Eq.\ \ref{eq:ctprnine}

becomes

![{\displaystyle a_{b}^{[2]}\approx {\frac {1}{4\hbar ^{2}}}{\frac {H_{bk,2}H_{ka,1}}{\omega _{1}-\omega _{ka}}}{\frac {e^{i(\omega _{0}-\omega _{1}-\omega _{2})t}-1}{\omega _{0}-\omega _{1}-\omega _{2}}}.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/8c64524b6dd71d934929ca42bcbba759a33413b5)

We then obtain for the transition probability

![{\displaystyle W_{a\rightarrow b}^{[2]}={\frac {1}{\left(4\hbar ^{2}\right)^{2}}}{\frac {|H_{bk,2}|^{2}|H_{ka,1}|^{2}}{(\omega _{1}-\omega _{ka})^{2}}}{\frac {\sin ^{2}\left[(\omega _{0}-\omega _{1}-\omega _{2})t/2\right]}{[(\omega _{0}-\omega _{1}-\omega _{2})/2]^{2}}}.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/cf52b235d890591a2b74c238998a6c3a297877b8)

Recalling that

![{\displaystyle {\frac {\sin ^{2}\left[(\omega _{0}-\omega _{1}-\omega _{2})t/2\right]}{[(\omega _{0}-\omega _{1}-\omega _{2})/2]^{2}}}{\xrightarrow[{t\rightarrow \infty }]{}}2\pi t\delta (\omega _{0}-\omega _{1}-\omega _{2}),}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/ec23f6a89d79292a7a49e6172bab1c7a609c3c5d)

we obtain

Integrating over the appropriate spectral distribution gives

We can cast the transition rate into a more familiar form by introducing the usual

Rabi frequencies

Denoting the detuning of the intermediate state by

we can define the two-photon Rabi frequency by

and we have

in analogy with the expression for one-photon transitions.

A more useful expression for the two-photon transition rate is in

terms of the radiation intensity,  . Noting that

. Noting that  (cgs units), we have from Eq.\ \ref{eq:ctprtwo}

(cgs units), we have from Eq.\ \ref{eq:ctprtwo}

Eq.\ \ref{eq:ctpathree} becomes

In the case where both photons emanate from a single laser beam, equation \ref{eq:ctpasix} further simplifies to

Discussion

Applicability of one-photon results

The definition above of a two-photon Rabi frequency suggests an analogy between two-photon and one-photon transitions. The analogy is a powerful one, as many results from the study of one-photon transitions carry over to the two-photon case. These include

- Lineshape: if the rate of spontaneous two-photon emission from

to

to  is

is  , then the transition has Lorentzian lineshape

, then the transition has Lorentzian lineshape

, where

, where  is the two-photon detuning.

is the two-photon detuning.

- Saturation: like single-photon transitions, two-photon transitions saturate as the rate of excitation approaches half the natural linewidth. By analogy with the one-photon case, one can define a two-photon saturation parameter

.

.

- Spontaneous emission: In calculating the rate of emission, we still have

, where

, where  and

and  is the number of photons in the mode of frequency

is the number of photons in the mode of frequency  ; the two-photon emission rate thus scales as

; the two-photon emission rate thus scales as  , where for every

, where for every  emission events in which both photons are stimulated, there is one event in which both photons are spontaneous, and there are

emission events in which both photons are stimulated, there is one event in which both photons are spontaneous, and there are  events in which the photon in mode

events in which the photon in mode  is stimulated and the other is spontaneous. The rate of absorption is the same as the rate of doubly-stimulated emission.

is stimulated and the other is spontaneous. The rate of absorption is the same as the rate of doubly-stimulated emission.

- The two-photon transition rate

looks similar to

looks similar to  (the rate of one-photon emission at frequency

(the rate of one-photon emission at frequency  ), but is diminished by

), but is diminished by ![{\displaystyle \left[{\frac {\omega _{R}^{(1)}}{2\Delta }}\right]^{2}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/fb3fdd79e0f3bdbd82224754ec83216ad5dbad43) , the squared amplitude of state

, the squared amplitude of state  admixed into state

admixed into state  .

.

- Two-photon emission: Consider the case where the population is initially in state

, but there is only one laser, and its frequency is close to the

, but there is only one laser, and its frequency is close to the  transition. Then the two photon emission rate is

transition. Then the two photon emission rate is

![{\displaystyle \Gamma _{ba}^{\mathrm {2-ph} }=\Gamma _{ka}\left[{\frac {H_{kb,1}}{2\Delta }}\right]^{2},}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/51a0a838f69cc3d14af8508753e0d9f32d5ec0c2) where

where  is the rate of spontaneous emission from

is the rate of spontaneous emission from  to

to  and

and ![{\displaystyle \left[{\frac {H_{kb,1}}{2\Delta }}\right]^{2}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/5045eed055ce2e320e71329782faab296e3f4959) is the admixture of state

is the admixture of state  into the initial state. This admixture may also be regarded as the "population of the virtual state."

into the initial state. This admixture may also be regarded as the "population of the virtual state."

What is the virtual state?

In calculating rates of two-photon processes, we have been making use of a "virtual" state near some intermediate state  with one-photon couplings to both the initial state

with one-photon couplings to both the initial state  and the final state

and the final state  . We have also noted that, more generally, the virtual state can be a superposition of several states---but all at the frequency of the drive. We can think of the virtual state purely mathematically as the thing that appears in the perturbation sum. But does it have a physical interpretation? To what extent does the transition from

. We have also noted that, more generally, the virtual state can be a superposition of several states---but all at the frequency of the drive. We can think of the virtual state purely mathematically as the thing that appears in the perturbation sum. But does it have a physical interpretation? To what extent does the transition from  to

to  occur via

occur via  ? And how can

? And how can  serve as an intermediate state given that the transitions into and out of

serve as an intermediate state given that the transitions into and out of  apparently do not conserve energy?

One interpretation is in the dressed atom picture (covered in 8.422). Because of the couplings introduced by the laser field, the true eigenstates of the system are not

apparently do not conserve energy?

One interpretation is in the dressed atom picture (covered in 8.422). Because of the couplings introduced by the laser field, the true eigenstates of the system are not  ,

,  , and

, and  but the so-called "dressed states." If we start with the system in

but the so-called "dressed states." If we start with the system in  and adiabatically turn on the field coupling

and adiabatically turn on the field coupling  to

to  , the system will evolve into the dressed state

, the system will evolve into the dressed state  . As we have seen above and will see again in the case of spontaneous Raman scattering, the rates of two-photon processes can often be understood in terms of this admixture of

. As we have seen above and will see again in the case of spontaneous Raman scattering, the rates of two-photon processes can often be understood in terms of this admixture of  into

into  , the "population of the virtual state"

, the "population of the virtual state"  . Thus, one can interpret the virtual state as a component of the dressed atom wavefunction.

Another way to understand the virtual state is to consider the lifetime of the atom in the intermediate state. Consider the case of two-photon emission from

. Thus, one can interpret the virtual state as a component of the dressed atom wavefunction.

Another way to understand the virtual state is to consider the lifetime of the atom in the intermediate state. Consider the case of two-photon emission from  to

to  via

via  . Although a transition from

. Although a transition from  to

to  violates energy conservation by an amount

violates energy conservation by an amount  , the Heisenberg uncertainty principle allows the atom to remain in the intermediate state for a time

, the Heisenberg uncertainty principle allows the atom to remain in the intermediate state for a time  . And indeed, if one observes the emitted photons, one finds that the two photons are correlated in time to within

. And indeed, if one observes the emitted photons, one finds that the two photons are correlated in time to within  .

.

Raman Processes

Stimulated Raman scattering

We have considered two-photon absorption processes, but stimulated

emission can also occur as can be seen from Fig.~\ref{fig:two-photon}.

Raman emission. Photon

can be emitted spontaneously, or by stimulated emission.

In this case, the transition  occurs by absorbing

a photon at frequency

occurs by absorbing

a photon at frequency  , and emitting a photon at

frequency

, and emitting a photon at

frequency  . If the transition is stimulated by two

applied radiation fields, then the process is known as stimulated

Raman scattering. If

. If the transition is stimulated by two

applied radiation fields, then the process is known as stimulated

Raman scattering. If  , the emission is

called Stokes radiation. If

, the emission is

called Stokes radiation. If  , the emission

is called anti-Stokes radiation. In either case, the frequencies

are related by

, the emission

is called anti-Stokes radiation. In either case, the frequencies

are related by

Our treatment of the two-photon transition applies, except that

one interaction step corresponds to emission, rather than

absorption. The change is trivial: the counter-rotating term at

frequency  in Eq.\ \ref{eq:ctprone}, which was

dropped, is retained and the rotating term, at frequency

in Eq.\ \ref{eq:ctprone}, which was

dropped, is retained and the rotating term, at frequency

, is dropped in its place. This merely changes the

sign of

, is dropped in its place. This merely changes the

sign of  in the ensuing steps, so we again obtain

in the ensuing steps, so we again obtain

where  as before, but in this case

as before, but in this case

Spontaneous Raman scattering

An important aspect of Raman scattering that differentiates it

from two-photon absorption is that the emission of the photon at

frequency  can be spontaneous. Spontaneous emission is

generally too slow to be useful at low frequencies but in the

optical regime the spontaneous rate can be large enough to cause

a sizeable scattering signal. Initially, spontaneous Raman

scattering was the only important process: not until the advent

of the laser did stimulated Raman scattering became useful.

We can estimate the rate of spontaneous Raman scattering by

considering absorption at

can be spontaneous. Spontaneous emission is

generally too slow to be useful at low frequencies but in the

optical regime the spontaneous rate can be large enough to cause

a sizeable scattering signal. Initially, spontaneous Raman

scattering was the only important process: not until the advent

of the laser did stimulated Raman scattering became useful.

We can estimate the rate of spontaneous Raman scattering by

considering absorption at  and emission at

and emission at  as separate processes, though strictly speaking only one process

is involved. We start by evaluating the spontaneous emission at

as separate processes, though strictly speaking only one process

is involved. We start by evaluating the spontaneous emission at

. This takes place from a virtual intermediate state,

which we shall denote as

. This takes place from a virtual intermediate state,

which we shall denote as  . The spontaneous emission rate is

given by the familiar expression

. The spontaneous emission rate is

given by the familiar expression

Next, we consider the problem of "populating" the virtual state.

The rate of exciting the state can be expressed in terms of the

Rabi frequency

The detuning from state  is

is  .

The transition rate to the intermediate state is approximately

.

The transition rate to the intermediate state is approximately

The time  the atom can occupy the state, however, is limited

by

the uncertainty principle to

the atom can occupy the state, however, is limited

by

the uncertainty principle to  . Hence the

probability

that state

. Hence the

probability

that state  is occupied is roughly

is occupied is roughly  . Using either perturbration theory or the dressed atom picture, one can solve for the virtual state population with the correct numerical factor:

. Using either perturbration theory or the dressed atom picture, one can solve for the virtual state population with the correct numerical factor:  .

Putting the above together, we obtain the rate for

spontaneous Raman scattering from

.

Putting the above together, we obtain the rate for

spontaneous Raman scattering from  to

to  :

:

Since  , the spontaneous Raman

rate depends linearly on the power. The absorption process can be

continued, allowing multi-photon Raman transitions to a final

state.

Note that even if a = b (i.e., if the internal state of the atom is unchanged by the two-photon transition), the final state differs from the initial state by one photon recoil. Hence, resonant fluorescence and Rayleigh scattering are Raman processes!

, the spontaneous Raman

rate depends linearly on the power. The absorption process can be

continued, allowing multi-photon Raman transitions to a final

state.

Note that even if a = b (i.e., if the internal state of the atom is unchanged by the two-photon transition), the final state differs from the initial state by one photon recoil. Hence, resonant fluorescence and Rayleigh scattering are Raman processes!

Two-photon Doppler-free spectroscopy

The Doppler effect is the most common source of inhomogeneous line

broadening. (Inhomogeneous broadening occurs because the

resonance frequencies of different atoms are shifted by different

amounts, giving a width to the ensemble. This is in contrast to

homogeneous broadening, when the response of each atom is the

same, as in the case of spontaneous decay.) If two-photon

excitation involves absorption from two light beams with

frequencies and wave vectors  and

and  , respectively, where

, respectively, where  , then the

frequencies "seen" by an

atom moving with velocity v are, to first order in v/c,\\

, then the

frequencies "seen" by an

atom moving with velocity v are, to first order in v/c,\\

The line shape function for an atom moving with velocity v is

The Doppler effect is minimized by taking  ,

in which case the shift is

,

in which case the shift is

The ensemble line shape function is obtained by averaging over the

distribution of velocities. Clearly, it is desirable to use

frequencies as similar as possible. The ideal case is when  , which would occur in two photon-absorption

from counter-propagating beams from the same laser. The simplest

way to assure counter-propagating beams is to use a standing wave.

Consequently, two-photon absorption in a standing wave displays no

first-order Doppler broadening. Nevertheless, there is a residual

second-order Doppler broadening. The second-order Doppler shift

is given by

, which would occur in two photon-absorption

from counter-propagating beams from the same laser. The simplest

way to assure counter-propagating beams is to use a standing wave.

Consequently, two-photon absorption in a standing wave displays no

first-order Doppler broadening. Nevertheless, there is a residual

second-order Doppler broadening. The second-order Doppler shift

is given by

Two-photon doppler-free spectrum. A narrow peak due to the process involving two photons from counterpropagating beams sits atop a broad pedestal due to that involving pairs of photons from the same beam.

Taking  , we have

, we have

At room temperature,  eV.

For hydrogen,

eV.

For hydrogen,  GeV . Consequently,

the fractional second order Doppler shift is about

GeV . Consequently,

the fractional second order Doppler shift is about  .

If one considers spectroscopy at a resolution of 1 part in

.

If one considers spectroscopy at a resolution of 1 part in

or better, the second order Doppler shift can be a major

source of systematic error. Fortunately, methods have been

developed for cooling below a millikelvin, where the effect is

unimportant, at least for the next few years. Also, in heavier

atoms, the second order Doppler effect is correspondingly

diminished.

A particularly important case is two-photon absorption on the

or better, the second order Doppler shift can be a major

source of systematic error. Fortunately, methods have been

developed for cooling below a millikelvin, where the effect is

unimportant, at least for the next few years. Also, in heavier

atoms, the second order Doppler effect is correspondingly

diminished.

A particularly important case is two-photon absorption on the  transition in hydrogen. The 2S state is

metastable and has a lifetime of 1/7 sec, yielding an extremely

high Q for the transition and the possibility of ultra-high

spectral resolution. The excitation operator has been calculated

for hydrogen by \cite{Bassani1977}. The result yields

transition in hydrogen. The 2S state is

metastable and has a lifetime of 1/7 sec, yielding an extremely

high Q for the transition and the possibility of ultra-high

spectral resolution. The excitation operator has been calculated

for hydrogen by \cite{Bassani1977}. The result yields

where the intensity  is now expressed in W

is now expressed in W . A transition becomes saturated when the transition rate

equals half the linewidth, or

. A transition becomes saturated when the transition rate

equals half the linewidth, or  . The

required power is only 0.6 W

. The

required power is only 0.6 W .

By using two-photon Doppler-free excitation in hydrogen,

H\"{a}nsch and his group have been able to achieve an experimental

linewidth below 10 kHz \cite{Niering2000}. The linewidth is dominated by the

time of flight of the atoms across the laser beam. Although the experimental linewidth of several

kHz may seem large compared to the natural linewidth of 1 Hz, it

is impressively narrow considering that the spectral linewidth

was many MHz not many years ago.

.

By using two-photon Doppler-free excitation in hydrogen,

H\"{a}nsch and his group have been able to achieve an experimental

linewidth below 10 kHz \cite{Niering2000}. The linewidth is dominated by the

time of flight of the atoms across the laser beam. Although the experimental linewidth of several

kHz may seem large compared to the natural linewidth of 1 Hz, it

is impressively narrow considering that the spectral linewidth

was many MHz not many years ago.

Notes

![{\displaystyle a_{f}^{[1]}={\frac {1}{2i\hbar }}\int _{0}^{t}{\left[H_{fa,1}e^{-i(\omega _{1}-\omega _{fa})t^{\prime }}+H_{fa,2}e^{-i(\omega _{2}-\omega _{fa})t^{\prime }}\right]dt^{\prime }}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/38559b260418a7c9986c0a71053694d255fde10b)

![{\displaystyle ={\frac {1}{2\hbar }}{\left[{\frac {H_{fa,1}(e^{-i(\omega _{1}-\omega _{fa})t}-1)}{\omega _{1}-\omega _{fa}}}+{\frac {H_{fa,2}(e^{-i(\omega _{2}-\omega _{fa})t}-1)}{\omega _{2}-\omega _{fa}}}\right]}.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/935f78b88c94694c2a0cb19d4dde8d346f562860)

![{\displaystyle a_{b}^{[2]}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/278368d4b1e3e7e1f4784fa2317a18e367883f46)

![{\displaystyle i\hbar {\dot {a}}_{b}^{[2]}=\sum _{k}H_{bk}a_{k}^{[1]}e^{i\omega _{bk}.t}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/01e7c88170f91f6c7bd434f2a71b568f4af3c1d5)

![{\displaystyle a_{b}^{[2]}={\frac {1}{i\hbar }}\int _{0}^{t}\langle b|H|f\rangle e^{i\omega _{bf}t^{\prime }}a_{f}^{[1]}(t^{\prime })dt^{\prime }.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/94d7797523cd3b2b6baeefff4f653ee5338c84a5)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{array}{rcl}a_{b}^{[2]}&=&{\frac {1}{4\hbar ^{2}}}\sum _{f}\left[{\frac {H_{bf,1}H_{fa,1}}{\omega _{1}-\omega _{fa}}}{\frac {e^{i(\omega _{0}-2\omega _{1})t}-1}{\omega _{0}-2\omega _{1}}}+{\frac {H_{bf,2}H_{fa,2}}{\omega _{2}-\omega _{fa}}}{\frac {e^{i(\omega _{0}-2\omega _{2})t}-1}{\omega _{0}-2\omega _{2}}}\right.\\&&+\left.{\frac {H_{bf,2}H_{fa,1}}{\omega _{1}-\omega _{fa}}}{\frac {e^{i(\omega _{0}-\omega _{1}-\omega _{2})t}-1}{\omega _{0}-\omega _{1}-\omega _{2}}}+{\frac {H_{bf,1}H_{fa,2}}{\omega _{2}-\omega _{fa}}}{\frac {e^{i(\omega _{0}-\omega _{1}-\omega _{2})t}-1}{\omega _{0}-\omega _{1}-\omega _{2}}}\right].\end{array}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/0999100eb41b4ffa8b191e958e4850b550748bdb)

![{\displaystyle a_{b}^{[2]}\approx {\frac {1}{4\hbar ^{2}}}{\frac {H_{bk,2}H_{ka,1}}{\omega _{1}-\omega _{ka}}}{\frac {e^{i(\omega _{0}-\omega _{1}-\omega _{2})t}-1}{\omega _{0}-\omega _{1}-\omega _{2}}}.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/8c64524b6dd71d934929ca42bcbba759a33413b5)

![{\displaystyle W_{a\rightarrow b}^{[2]}={\frac {1}{\left(4\hbar ^{2}\right)^{2}}}{\frac {|H_{bk,2}|^{2}|H_{ka,1}|^{2}}{(\omega _{1}-\omega _{ka})^{2}}}{\frac {\sin ^{2}\left[(\omega _{0}-\omega _{1}-\omega _{2})t/2\right]}{[(\omega _{0}-\omega _{1}-\omega _{2})/2]^{2}}}.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/cf52b235d890591a2b74c238998a6c3a297877b8)

![{\displaystyle {\frac {\sin ^{2}\left[(\omega _{0}-\omega _{1}-\omega _{2})t/2\right]}{[(\omega _{0}-\omega _{1}-\omega _{2})/2]^{2}}}{\xrightarrow[{t\rightarrow \infty }]{}}2\pi t\delta (\omega _{0}-\omega _{1}-\omega _{2}),}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/ec23f6a89d79292a7a49e6172bab1c7a609c3c5d)

![{\displaystyle \left[{\frac {\omega _{R}^{(1)}}{2\Delta }}\right]^{2}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/fb3fdd79e0f3bdbd82224754ec83216ad5dbad43)

![{\displaystyle \Gamma _{ba}^{\mathrm {2-ph} }=\Gamma _{ka}\left[{\frac {H_{kb,1}}{2\Delta }}\right]^{2},}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/51a0a838f69cc3d14af8508753e0d9f32d5ec0c2)

![{\displaystyle \left[{\frac {H_{kb,1}}{2\Delta }}\right]^{2}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/5045eed055ce2e320e71329782faab296e3f4959)