Non-classical states of light

Quantum states and dynamics of photons

Non-classical light

One of the most special properties of the coherent state is that its fluctuations in and are equal, and minimal, meaning that it satisfies the Heisenberg limit . However, satisfying this limit does not require equal noise in the two conjugate variables; it is certainly permissible for noise in one to be larger than the other. Such states can, in principle, be quite useful, for example, if a measurement only involves , and excess noise in can be disregarded. In this section, we define such squeezed states, and explore their physical properties. We begin with classical squeezing, then define squeezed states of a quantum simple harmonic oscillator, describe how squeezing can be experimentally detected, then show how it can be useful in a quantum experiment: teleportation.

Classical squeezing

We are interested in the dynamics of the simple harmonic oscillator, and it is useful to obtain some intuition about what is possible from considering the classical oscillator. Consider a particle in the potential

The equations of motion for this particle, have the solution

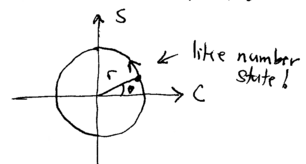

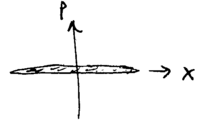

where , , and are constant. This motion is circular:

Suppose a small, "parametric" driving force is added, analogous to kicking while on a swing. For a swinging pendulum, this force could be applied by tugging gently up and down on the string as the pendulum oscillates back and forth. Let this force be applied at twice the frequency of the natural harmonic motion, such that the potential becomes

where is small.

Substituting Eq.(\ref{eq:c2-ansatz}) into the equation of motion

approximating , and averaging away terms rapidly oscillating at , we obtain new approximate equations of motion

with solutions

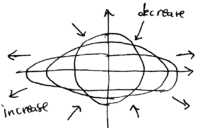

This shows that the circular motion in phase space evolves under the parametric drive to become elliptical:

What is the ultimate limit of this classical squeezing effect? The answer turns out to be quantum noise, which enforces the Heisenberg uncertainty limit, .

Squeezed states: quantum

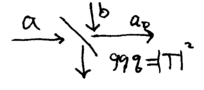

A quantum simple harmonic oscillator excited by a parametric drive at will also generate squeezed states. Physically, such a process corresponds to a "nonlinear" interaction which involves photons interacting with each other, via the medium they are transported through or generated from. One important physical process that generates squeezed states of light is known as the optical parametric oscillator, which we may think of as being an atomic system that is driven at , and produces two photons at and , due to cascaded decay from two equaly spaced energy levels:

Such a process can be described by the Hamiltonian

where acts on the output mode at frequency , and the input mode, at frequency . If the input light is a strong coherent field, then to a good approximation, we may replace and by a classical variable in this Hamiltonian, obtaining

where denotes the strength of the input pump light, and for simplicity, we fix in the following.

Motivated by this Hamiltonian for the optical parametric oscillator, we may define a mathematical operator which produces squeezed states:

Note that the operator in the exponent has the form , where is Hermitian, so is manifestly a unitary transform.

What does do? A useful mathematical technique for dealing with is to understand how it transforms operators in the Heisenberg picture. For example,

Let us use

as dimensionless Hermitean operators for position and momentum. Under the squeezing operator, using the above expansion, it is straightforward to show that position and momentum transform to become:

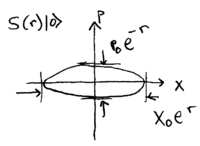

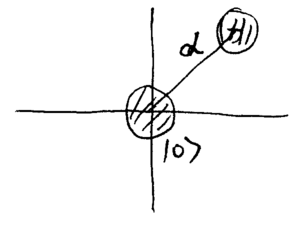

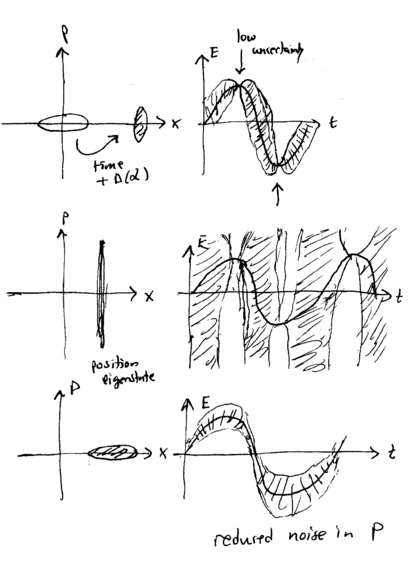

This shows that squeezes noise from the position, and adds noise to the momentum, of a harmonic oscillator state. Consider, for example, the effect of this operator on the vauum state, , which we call the "squeezed vacuum" state. The plot of this squeezed vacuum is:

\noindent Note that since is unitary, it leaves invariant, so is a minumim uncertainty state, since is.

We can explicitly compute what is as follows:

Note that this state only has nonzero probability amplitude to have an even number of photons!

Coherent state representation of squeezed states

Another usful representation for the squeezed vacuum is in terms of coherent states[1]:

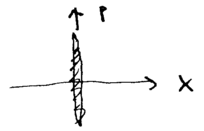

This representation allows us to depict useful limits, such as when , the inifinite squeezing limit, giving a state we may call :

and similarly, we may define

These two states have plots which are of infinite extent, horizontally (for ) and vertically (for ), indicating that infinitely squeezed states are position and momentum eigenstates:

The Displacement Operator

How can squeezing produce finite valued position and momentum eigenstates? Physically, a simple harmonic oscillator such as an oscillating pendulum is given a finite momentum or position by displacing the pendulum, and the same is done to produce squeezed states of and .

We define the mathematical displacement operator as

It is straightforward to show (by expanding the exponential, for example), that this operator has the property that

such that the displaced vacuum state satisfies

Since is thus an eigenstate of , it must be the case that . The displacement operator displaces the vacuum state to become a coherent state :

Using the displacement operator, squeezed states with finite momentum and position can thus be described, for example, by .

Electric Field of Squeezed States

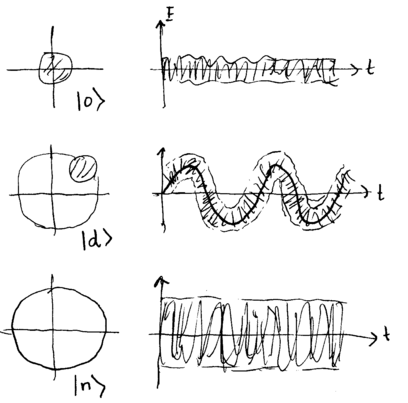

What do these states look like, both in the representation, as well as their electric field? Recall that the vacuum, coherent state, and number states look as follows:

A displaced, partially squeezed state, a near-position eigenstate, and a near-momentum eigenstate correspondingly look like this:

Note how the squeezed states attain electric fields which are, at times, very low in either amplitude or phase uncertainty. By employing these states in the right kind of interferometer, as we shall see later, this reduced noise level can be used to improve the precision of certain measurements.

Homodyne detection

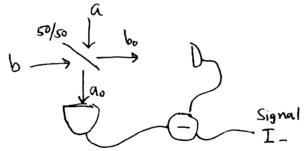

How can we experimentally detect if a state is squeezed? Ideally, squeezing could be detected by measuring the noise level in and . However, photodetectors are square-law detectors which sense light intensity, meaning photon number, and not quadrature field components. Nevertheless, the and field components can be detected if the input light is first transformed by beating it with a reference signal of fixed phase. Intuitively, this follows the principle upon which many early radios worked: by mixing a signal with a reference oscillator , the cosine and sine components and can be picked out. This method is known as homodyne detection, because it involves mixing with a reference at the same frequency as the signal. With radio frequency signals, a diode is used to mix signal and reference; the nonlinearity of the diode produces an output which is to first order, the product of the signal and reference. Mixing of light frequency signals is done with a beamsplitter. Consider a 50/50 beamsplitter with the signal input into port , and the reference into port , and detectors placed at the two outputs:

The beamsplitter mixes the two input ports, performing a unitary transform that relates the output port operators and to the input port operators and ,

Note that we have adopted a convention which does away with imaginary phases, for convenience; in the literature, you may find different convention used, to reflect phases imparted by actual half-silvered mirror beamsplitters used in the laboratory. The detected signal thus results from

If mode has a strong coherent state as input, with , then we may write as a normalized output signal,

Two important values of this signal are

This thus shows how a beamsplitter and a strong coherent state input source can be used to experimentally measure and quadratures of a light field. The technique just described uses a 50/50 beamsplitter, and is known as "balanced homodyne" detection. A similar technique, using an unblanced beamsplitter, say one with transmission of the mode, is known as "unbalanced homodyne" mixing, and useful for a different purpose. Consider this setup:

The output port operator for may be expressed as

Now let a strong coherent state be input to port , such that to good approximation, in the limit that , we may write

Unbalanced homodyne mixing thus allows approximation experimental implementation of a displacement operation.

Teleportation of light

We conclude this section with an exploration of an exotic application of squeezed states: the teleportation of a quantum state of light. In order to clearly convey the basic concepts, this treatment will emphasize empirical understanding, above mathematical rigor. So far, we have limited ourselves to studying a single mode of light. It is not hard to see, however, that two-mode squeezed states are also possible, and that for example, straightforward generalization of the squeezing operator from Eq.(\ref{eq:c2-sdef}) to two modes gives

This state can also be expressed as a superposition of coherent states, of the form

and given that momentum and position eigenstates can be expressed as infinite superpositions of coherent states, as in Eqs.(\ref{eq:c2-mstate}-\ref{eq:c2-pstate}), it is reasonable to believe that such an infinitely-squeezed two-mode state could be expressed (in unnormalized form) as

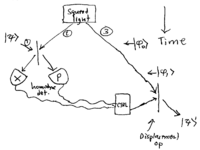

where represents a position basis state. Let us begin with such an infinitely-squeezed two-mode state, and show how a state of light can be teleported. In the following, state vectors and will denote position basis states, will denote a momentum basis state, and the subscript will deliniate the mode. Three modes will be involved. Overall normalization factors will be neglected. The setup is as follows:

\noindent where the initial state begins at the top of the diagram, and time evolves downward. Modes and contain the squeezed state, and an unknown quantum state

is input. The main idea is that modes and belong to one person (call her "Alice"), and mode belongs to another person ("Bob"). Alice and Bob jointly share the two-mode squeezed state, which was distributed to them long before came into existence. Only Alice has , and she would like to communicate it to Bob, but the quantum link is down, and all she can do is to mail him a classical message. Normally, this would be impossible, but, because they have the pre-shared two-mode squeezed state, they can use it to communicate , following this procedure. The initial state of the three modes is

The first two modes are now sent through a beamsplitter, resulting in

Recall that position eigenstates may be expressed as weighted sums over momentum eigenstates, as

so that may be equivalently expressed as

Alice now measures the photons in her two modes; she performs a homodyne -measurement of mode , and a -measurement of mode . Let and be her measurement results. The post-measurement state is

Changing variables from to , this becomes

which is just a displaced version of the original state, up to an irrelevant overall phase:

Thus, if Alice sends Bob her measurement results and , then he can reconstruct by applying the displacement using an unbalanced homodyne operation. The elegance of this version of quantum teleportation is in its experimental implementation: given the two-mode squeezed state, everything else in the protocol is experimentally straightforward. Indeed, this is why the above procedure has been experimentally implemented. Go read about it: Furusawa et al, Science vol. 282, p.706, 1998.

![{\displaystyle {\begin{array}{rcl}x(t)&=&r(t)\cos \left[{\omega _{0}t-\theta (t)}\right]\\&=&c(t)\cos \omega _{0}t+s(t)\sin \omega _{0}t\,,\end{array}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/ed1126f0314b124b847a7002315b85c3ebe46531)

![{\displaystyle V(x)={\frac {1}{2}}m\omega _{0}^{2}x^{2}\left[{1+\epsilon \sin 2\omega _{0}t}\right]\,,}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/edff86a2e3d12726d0213449d5ae7228eefca2d0)

![{\displaystyle {\ddot {x}}=-\omega _{0}^{2}\left[{1+\epsilon \sin 2\omega _{0}t}\right]x(t)\,,}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c1e3676b6d9d447947628c0faa1a8c06be12dca6)

![{\displaystyle S(r)=\exp \left[{-{\frac {r}{2}}(a^{2}-{a^{\dagger }}^{2})}\right]\,.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/fa8fdf415b0d7a2de52f5ac51d302e2e76b6e0cd)

![{\displaystyle S(r)=\exp[iA]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/36c5cb1ef21f7609c7218e2a536b288698c49569)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{array}{rcl}S(r)xS(r)^{\dagger }&=&e^{iA}xe^{-iA}\\&=&x+[iA,x]+{\frac {[iA,[iA,x]]}{2!}}+\cdots \,,\end{array}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/436a68184a6b6900e56cbb70cbdc460340bcc08a)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{array}{rcl}S(r)|0\rangle &=&\sum _{k=0}^{\infty }{\frac {1}{k!}}\left[{-{\frac {r}{2}}(a^{2}-{a^{\dagger }}^{2})}\right]^{k}|0{\rangle }\\&=&{\frac {1}{\sqrt {\cosh r}}}\sum _{n=0}^{\infty }{\frac {\sqrt {(2n)!}}{2^{n}n!}}(\tanh r)^{n}|2n{\rangle }\,.\end{array}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/5ddf7dcb3b019cbc045a92cdab3abbc501b1ad3f)

![{\displaystyle D(\alpha )=\exp \left[{\alpha a^{\dagger }-\alpha ^{*}a}\right]\,.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/b380dce7a8eb51fea894d41eddb7f38170b2b89c)

![{\displaystyle \exp \left[{-{\frac {r}{2}}(a_{1}a_{2}-a_{1}^{\dagger }a_{2}^{\dagger })}\right]|0\rangle _{1}|0\rangle _{2}={\frac {1}{\cosh r}}\sum _{n}\tanh ^{n}r|n\rangle _{1}|n\rangle _{2}\,.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/377932d0fcfa31eba6fa2d20049b8ab13e926fcc)