Introduction

Immediately adjacent to Michelson and Morley's announcement of

their failure to find the ether in

an 1887 issue of the Philosophical Journal is a paper by the same

authors reporting that the

H line of hydrogen is actually a doublet, with a

separation of 0.33 cm

line of hydrogen is actually a doublet, with a

separation of 0.33 cm . In 1915

Bohr suggested that this "fine structure" of hydrogen is a

relativistic effect arising from the

variation of mass with velocity. Sommerfeld, in 1916, solved the

relativistic Kepler problem and

using the old quantum theory, as it was later christened, accounted

precisely for the splitting.

. In 1915

Bohr suggested that this "fine structure" of hydrogen is a

relativistic effect arising from the

variation of mass with velocity. Sommerfeld, in 1916, solved the

relativistic Kepler problem and

using the old quantum theory, as it was later christened, accounted

precisely for the splitting.

Sommerfeld's theory gave the lie to Einstein's dictum "The Good

Lord is subtle but not

malicious", for it gave the right results for the wrong reason:

his theory made no provision for

electron spin, an essential feature of fine structure. Today, all

that is left from Sommerfeld's

theory is the fine structure constant  .

The theory for the fine structure in hydrogen was provided by Dirac

whose relativistic electron theory (1926) was applied to hydrogen

by Darwin and Gordon in 1928. They found the following expression for

the energy of an electron bound to a proton of infinite mass:

.

The theory for the fine structure in hydrogen was provided by Dirac

whose relativistic electron theory (1926) was applied to hydrogen

by Darwin and Gordon in 1928. They found the following expression for

the energy of an electron bound to a proton of infinite mass:

![{\displaystyle {\frac {E}{mc^{2}}}={\left[{\frac {1}{\sqrt {\frac {\alpha Z}{n-k+{\sqrt {k^{2}-\alpha ^{2}Z^{2}}}}}}}\right]^{2}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/57b03decb353205d3f96fa4b7d5d1c6a760ee73f)

where  is the principal quantum number,

is the principal quantum number,  , and

, and  .

The Dirac equation is not nearly as illuminating as the Pauli

equation, which is the approximation to the Dirac equation to the

lowest order in v/c.

.

The Dirac equation is not nearly as illuminating as the Pauli

equation, which is the approximation to the Dirac equation to the

lowest order in v/c.

The first term is the electron's rest energy; the following two

terms

are the non relativistic Hamiltonian, and the last term, the fine structure

interaction, is given by

The relativistic contributions can be described as the kinetic, spin-orbit, and Darwin terms,  ,

,  , and

, and  ,

respectively. Each has a straightforward

physical interpretation.

,

respectively. Each has a straightforward

physical interpretation.

Kinetic contribution

Relativistically, the total electron energy is E =  . The kinetic energy is

. The kinetic energy is

![{\displaystyle T=E-mc^{2}=(mc^{2}){\left[{\sqrt {1+{\frac {p^{2}}{m^{2}c^{2}}}}}-1~~\right]}={\frac {p^{2}}{2m}}-{\frac {1}{8}}{\frac {p^{4}}{m^{3}c^{2}}}+\cdots }](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/fc695e8be75e63a5d72e966b6e14fd7eeb899702)

Thus

Spin-Orbit Interaction

According to the Dirac theory the electron has intrinsic angular

momentum  and a magnetic moment

and a magnetic moment  . The electron g-factor,

. The electron g-factor,  . As the electron

moves through the electric field of the proton it "sees" a

motional

magnetic field

. As the electron

moves through the electric field of the proton it "sees" a

motional

magnetic field

where  . However, there is

another contribution to the

effective magnetic field arising from the Thomas precession.

The relativistic transformation of a vector between two moving co-

ordinate systems which are moving with different velocities involve

not only a dilation, but also a rotation (cf Jackson,

{\it Classical Electrodynamics}).

The rate of rotation, the Thomas precession, is

. However, there is

another contribution to the

effective magnetic field arising from the Thomas precession.

The relativistic transformation of a vector between two moving co-

ordinate systems which are moving with different velocities involve

not only a dilation, but also a rotation (cf Jackson,

{\it Classical Electrodynamics}).

The rate of rotation, the Thomas precession, is

Note that the precession vanishes for co-linear acceleration.

However, for a vector fixed in a co-ordinate system moving around a

circle, as in the case of the spin vector of the electron as it

circles the proton, Thomas precession occurs. From the point of

view

of an observer fixed to the nucleus, the precession of the electron

is

identical to the effect of a magnetic field.

Substituting  , and

, and  into Eq.\ \ref{EQ_soitwo} gives

into Eq.\ \ref{EQ_soitwo} gives

Hence the total effective magnetic field is

This gives rise to a total spin-orbit interaction

The Darwin Term

Electrons exhibit "Zitterbewegung", fluctuations in position on

the order of the Compton

wavelength,  . As a result, the effective Coulombic

potential is not

. As a result, the effective Coulombic

potential is not  , but some

suitable average

, but some

suitable average  , where the average is

over the characteristic

distance

, where the average is

over the characteristic

distance  . To evaluate this, expand

. To evaluate this, expand  about

about

in terms of a

displacement

in terms of a

displacement  ,

,

Assume that the fluctuations are isotropic. Then the time average

of

is

is

![{\displaystyle \Delta V\sim {\frac {1}{2}}{\left[{\frac {1}{3}}{\left({\frac {\hbar }{mc}}\right)^{2}}\right]}\nabla ^{2}V=-{\frac {1}{6}}{\frac {e^{2}\hbar ^{2}}{m^{2}c^{2}}}\nabla ^{2}\left({\frac {1}{r}}\right)}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/90dd5f34606adfcb4dbc1b8d5ca7df80561feedb)

The precise expression for the Darwin term is

The coefficient of the Darwin term is 1/8, rather than 1/6.

Recall that  , so that the Darwin term is nonzero only for

, so that the Darwin term is nonzero only for  states, where

states, where  .

That is, the Zitterbewegung effectively cuts off the cusp of the

.

That is, the Zitterbewegung effectively cuts off the cusp of the  potential, thereby reducing the binding energy for

potential, thereby reducing the binding energy for  -electrons.

-electrons.

Evaluation of the fine structure interaction

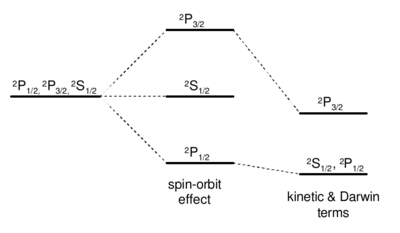

Fine structure of  levels in hydrogen. The degeneracy between the

levels in hydrogen. The degeneracy between the  and

and  levels, which looks accidental in non-relativistic quantum mechanics, is really deeply rooted in the relativistic nature of the system. The degeneracy is ultimatly broken in QED by the Lamb Shift.

levels, which looks accidental in non-relativistic quantum mechanics, is really deeply rooted in the relativistic nature of the system. The degeneracy is ultimatly broken in QED by the Lamb Shift.

The spin orbit-interaction is not diagonal in  or {\bf

S} due to the term

or {\bf

S} due to the term  . However, it is diagonal

in

. However, it is diagonal

in

.

.  and

and  are likewise

diagonal in

are likewise

diagonal in  . Hence, finding the energy level structure

due

to the fine structure interaction involves evaluating

. Hence, finding the energy level structure

due

to the fine structure interaction involves evaluating

.

Note that

.

Note that  vanishes in an

vanishes in an  state, and that

state, and that

vanishes in all states but an

vanishes in all states but an  state. It is left as an

exercise to show that

state. It is left as an

exercise to show that

Note that states of a given  and

and  are degenerate. This

degeneracy

is a crucial feature of the Dirac theory.

are degenerate. This

degeneracy

is a crucial feature of the Dirac theory.

The Lamb Shift

According to the Dirac theory, states of the hydrogen atom with the

same values of  and

and  are degenerate. Hence, in a given term,

(

are degenerate. Hence, in a given term,

( ), (

), ( ), (

), ( ), etc. form degenerate

doublets. However, as described in Chapter 1, this is not exactly

the

case. Because of vacuum interactions, not taken into account, in

the

Dirac theory, the degeneracy is broken. The largest effect is in

the

), etc. form degenerate

doublets. However, as described in Chapter 1, this is not exactly

the

case. Because of vacuum interactions, not taken into account, in

the

Dirac theory, the degeneracy is broken. The largest effect is in

the

state. The energy splitting between the

state. The energy splitting between the  and

and

states is called the Lamb Shift. A

simple physical model due to Welton and Weisskopf demonstrate its

origin. In the following derivation, note the analogy between the vacuum

fluctuations inducing the Lamb Shift and the Zitterbewegung responsible for the

Darwin term treated in section \ref{SEC_dt}.

Because of zero point fluctuation in the vacuum, empty space is not

truly empty. The electromagnetic modes of free space behave like

harmonic oscillators, each with zero-point energy

states is called the Lamb Shift. A

simple physical model due to Welton and Weisskopf demonstrate its

origin. In the following derivation, note the analogy between the vacuum

fluctuations inducing the Lamb Shift and the Zitterbewegung responsible for the

Darwin term treated in section \ref{SEC_dt}.

Because of zero point fluctuation in the vacuum, empty space is not

truly empty. The electromagnetic modes of free space behave like

harmonic oscillators, each with zero-point energy  . The

density of modes per unit frequency interval and per volume is

given

by the well known expression

. The

density of modes per unit frequency interval and per volume is

given

by the well known expression

Consequently, the zero-point energy density is

With this energy we can associate a spectral density of radiation

The bar denotes a time average and  and

and  are the

field amplitudes. Hence,

are the

field amplitudes. Hence,

For the moment we shall treat the electron as if it were free. Its

motion is given by

The effect of the fluctuation  is to cause a change

is to cause a change

in the average potential

in the average potential

can be found by a Taylor's expansion:

can be found by a Taylor's expansion:

When we average this in time, the second term vanishes because {\bf

s} averages to zero. For the

same reason, in the final term, only contributions with  remain. We have, taking the average,

remain. We have, taking the average,

Since  we

obtain finally

we

obtain finally

Since  , we

obtain

the following expression for the change in energy

, we

obtain

the following expression for the change in energy

The matrix element gives contributions only for  states, where

its

value is

states, where

its

value is

Combining Eqs.\ \ref{EQ_lambsix}, \ref{EQ_lambtweleve} into Eq.\

\ref{EQ_lambeleven} yields

Integrating over some yet to be specified frequency limits, we

obtain

At this point, atomic units come in handy. Converting by the usual

prescription, we obtain

The question remaining is how to choose the cut-off frequencies for

the integration. It is reasonable that  is

approximately

the frequency of an orbiting electron,

is

approximately

the frequency of an orbiting electron,  in atomic

units. At lower energies, the electron could not respond. For the

upper limit, a plausible guess is the rest energy of the electron,

in atomic

units. At lower energies, the electron could not respond. For the

upper limit, a plausible guess is the rest energy of the electron,

. Hence,

. Hence,  .

For the

.

For the  state, this gives

state, this gives

atomic~units

atomic~units  MHz

MHz

The actual value is 1,058 MHz.

Measurements of the Lamb shift \cite{Lamb1947, Weitz1994, Schwob1999} have occupied the forefront of hydrogen spectroscopy from Lamb's original 1947 discovery, using microwave techniques, of a shift of "about 1000 Mc/sec" to more recent results at the  level of precision obtained in the optical domain by two-photon spectroscopy.

level of precision obtained in the optical domain by two-photon spectroscopy.

Notes

![{\displaystyle {\frac {E}{mc^{2}}}={\left[{\frac {1}{\sqrt {\frac {\alpha Z}{n-k+{\sqrt {k^{2}-\alpha ^{2}Z^{2}}}}}}}\right]^{2}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/57b03decb353205d3f96fa4b7d5d1c6a760ee73f)

![{\displaystyle T=E-mc^{2}=(mc^{2}){\left[{\sqrt {1+{\frac {p^{2}}{m^{2}c^{2}}}}}-1~~\right]}={\frac {p^{2}}{2m}}-{\frac {1}{8}}{\frac {p^{4}}{m^{3}c^{2}}}+\cdots }](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/fc695e8be75e63a5d72e966b6e14fd7eeb899702)

![{\displaystyle \Delta V\sim {\frac {1}{2}}{\left[{\frac {1}{3}}{\left({\frac {\hbar }{mc}}\right)^{2}}\right]}\nabla ^{2}V=-{\frac {1}{6}}{\frac {e^{2}\hbar ^{2}}{m^{2}c^{2}}}\nabla ^{2}\left({\frac {1}{r}}\right)}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/90dd5f34606adfcb4dbc1b8d5ca7df80561feedb)