Difference between revisions of "Tmp Lecture 25"

imported>Peyronel |

imported>Hofferbe |

||

| (79 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

Lecture XXV | Lecture XXV | ||

| − | + | ||

<br style="clear: both" /> | <br style="clear: both" /> | ||

| Line 12: | Line 8: | ||

Let us assume large one-photon detuning, <math>\Delta \gg \Gamma</math>, weak probe <math>\omega _1</math> and strong control field <math>\omega _2</math> (we also define the two-photon detuning <math>\delta =\Delta _1-\Delta _2</math>). | Let us assume large one-photon detuning, <math>\Delta \gg \Gamma</math>, weak probe <math>\omega _1</math> and strong control field <math>\omega _2</math> (we also define the two-photon detuning <math>\delta =\Delta _1-\Delta _2</math>). | ||

| − | + | [[Image:EIT_levels.jpg||400px]] | |

| − | + | In this limit analytic expressions for the absorption cross section for beam <math>\omega _1</math> and the refractive index seen by beam <math>\omega _1</math> exist, e.g. [[http://pra.aps.org/abstract/PRA/v56/i3/p2385_1 Muller et al., PRA 56, 2385 (1997)]] | |

| − | + | The refractive index is given by: <math>n(d)=1+\frac{3}{8\pi }\tilde{n}\lambda ^3f(\Delta )</math> | |

| − | + | where <math>\tilde{n}</math> is the atomic density, <math>f(\delta )=\frac{\Gamma}{2}\delta \frac{A}{A^2+B^2},A=\omega _2^2-\delta \Delta _2, B=\delta\Gamma</math>. | |

| − | + | For zero ground-state linewidth (decoherence between the ground-states) <math> \sigma(\delta)=\sigma_{0}.g\left(\delta\right)</math> where <math>\sigma_0=\frac{3}{2\pi}\lambda^2</math> is the resonant cross-section, and <math>g(\Delta)=\frac{\Gamma}{2}\frac{\delta B}{A^2+B^2}</math>. | |

| − | + | The absorption cross section for <math>\Delta _2>0</math>: | |

| − | Image | + | [[Image:Fano_profile.jpg||800px]] |

| + | |||

This is like a ground state coupling to one narrow and one wide excited state, except that there is EIT in between because both states decay to the same continuum. | This is like a ground state coupling to one narrow and one wide excited state, except that there is EIT in between because both states decay to the same continuum. | ||

| − | + | [[Image:New_states.jpg|center||300px]] | |

| − | + | At <math>\delta=\Delta _{2}</math> , we have one-photon absorption, which is a two-photon scattering process: | |

| − | + | [[Image:One_photon_abs.jpg|center||150px]] | |

| − | + | At <math>\delta=-\frac{\omega _2^2}{\Delta _2}</math>, two-photon absorption, which is (at least) four-photon scattering process: | |

| − | + | [[Image:Two_photon_abs.jpg|center||300px]] | |

| − | <math> | + | For the EIT condition <math>\delta =0</math>, there is no coupling to the excited state, and the refractive index is zero. In the vicinity of EIT, there is steep dispersion, resulting in a strong alteration of the group velocity of light<math>\rightarrow </math> slowing and stopping light. |

| − | Image | + | [[Image:Index_of_refraction.jpg||800px]] |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

<br style="clear: both" /> | <br style="clear: both" /> | ||

== Slow light, adiabatic changes of velocity of light == | == Slow light, adiabatic changes of velocity of light == | ||

| − | The group velocity of light in the presence of linear dispersion <math>\frac{dn}{d\omega }</math> is given by | + | The group velocity of light in the presence of linear dispersion <math>\frac{dn}{d\omega }</math> is given by [[http://prl.aps.org/abstract/PRL/v82/i23/p4611_1 Harris and Hau, PRL 82, 4611 (1999)]] |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | 82 | ||

| − | |||

| − | <math> | + | <math>v_ g=\frac{c}{1+\omega \frac{dn}{d\omega }}</math> for light at frequency <math>\omega </math>. |

| − | A strong linear dispersion with positive slope near EIT then corresponds to very slow light | + | A strong linear dispersion with positive slope near EIT then corresponds to very slow light. |

| − | + | As <math>n=1</math>, the electric field is unchanged so the power per area <math>\frac{P}{A}=\frac{1}{2}\epsilon _ oC|E|^2</math> also remains unchanged. | |

| − | + | Due to slowed group velocity, the pulse is compressed in the medium. As a consequence, the energy density is increased, and the light is partly in the form of an atomic excitation (coherent superposition of the ground states, although most of the energy is exchanged to the control field). | |

| − | + | [[Image:Pulse_compression.jpg||600px]] | |

| − | + | For sufficiently small <math>\omega _2</math>, the velocity of light may be very small, down to a few m/s [[http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v397/n6720/full/397559a0.html L.V. Hau, S.E. Harris et al., Nature 397, 594 (1999)]], as observed in a BEC. Reduced group velocity can also be observed in room-temperature experiment if the setup is Doppler free (co-propagating probe and control fields <math>\omega _1</math> and <math>\omega _2</math>) (otherwise only a small velocity class satisfies the two-photon resonance condition). | |

| − | + | If we change control field adiabatically while the pulse is inside the medium, we can coherently stop light, i.e. convert it into an atomic excitation or spin wave. With the reverse process we can then convert the stored spin-wave back into the original light field. The adiabatic conversion is made possible by the finite splitting between bright and dark states. In principle, all coherence properties and other (qm) features of the light are maintained, and it is possible to store non-classical states of light by mapping photon properties one-to-one onto quantized spin waves. We will learn more about these quanta called "dark-state polaritons" once we have introduced Dicke states. Is it possible to make use of EIT for, e.g. atom detection without absorption? Answer: no improvement for such linear processes. However: improvement for non-linear processes is possible. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

<br style="clear: both" /> | <br style="clear: both" /> | ||

| Line 84: | Line 63: | ||

Assume that two identical atoms, one in its ground and the other in its excited state, are placed within a distance <math>d\gg \lambda _{eg}</math> of each other. What happens? | Assume that two identical atoms, one in its ground and the other in its excited state, are placed within a distance <math>d\gg \lambda _{eg}</math> of each other. What happens? | ||

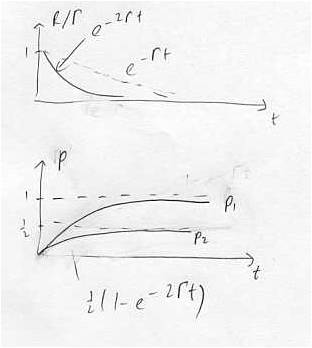

| − | For a | + | For a single atom we have, for the emission rate <math> R\left(t\right) </math> at time t is <math> R\left(t\right)=\Gamma e^{-\Gamma t}</math> (product of the spontaneous emission rate and occupation probability). Thus, the emission probability to have emitted a photon by time t is |

| + | |||

| + | {{EqL | ||

| + | |math=<math>p_{1}(t)=\int _0^ t R(t') dt'=1-e^{-\Gamma t}</math> | ||

| + | |num=eqtn:superradiance1 | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | |||

| − | |||

| − | Image | + | [[Image:Single_atoms_decay.jpg|frame|center||300px]] |

| − | + | What about two atoms? It turns out that the correct answer is | |

| − | + | {{EqL | |

| + | |math=<math>R_2\left(t\right)=\Gamma e^{-2 \Gamma t}</math> | ||

| + | |num=eqtn:superradiance2 | ||

| + | }} | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | {{EqL | |

| + | |math=<math>p_2(t)=\int ^ t_0 R_2(t')dt'=\frac{1}{2}(1-e^{-2rt})</math> | ||

| + | |num=eqtn:superradiance3 | ||

| + | }} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | [[Image:Two_atoms_decay.jpg|frame|center||300px]] | |

| − | + | The photon is emitted with the same initial rate, but has only probability <math>\frac{1}{2}</math> of being emitted at all! How can we understand this? The interaction Hamiltonian is (classically): | |

| − | + | {{EqL | |

| + | |math=<math>V=-\vec{d}_1\cdot \vec{E}(\vec\gamma ,t)-\vec{d}_2\cdot \vec{E}(\vec\gamma ,t)=-\vec{D}\cdot \vec{E}(\vec\gamma ,t)</math> | ||

| + | |num=eqtn:superradiance5 | ||

| + | }} | ||

| − | + | In QED: | |

| − | <math>V=\hbar g(\sigma ^+_1+\sigma ^-_1)(a+a^+)g(\sigma _2^++\sigma _2^-)(a+a^+) | + | {{EqL |

| + | |math=<math>V=\hbar g(\sigma ^+_1+\sigma ^-_1)(a+a^+)+\hbar g(\sigma _2^++\sigma _2^-)(a+a^+)</math> <math>=\hbar g(\sigma ^+_1+\sigma ^+_2+\sigma ^-_1+\sigma ^-_2)(a+a^+)=\hbar g(\Sigma ^++\Sigma ^-)(a+a^+)</math> | ||

| + | |num=eqtn:superradiance6 | ||

| + | }} | ||

| − | with <math>\Sigma ^{\pm } | + | with <math>\Sigma ^{\pm }=\Sigma ^ 2_{i=1}\sigma ^{\pm }_ i, \vec{D}=\Sigma ^ 2_{i=1}\vec{d}_ i</math> |

Latest revision as of 16:13, 19 April 2010

Lecture XXV

Two-phase absorption, Fano profiles

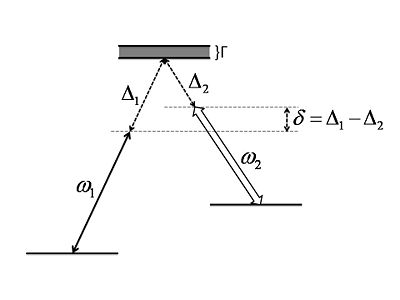

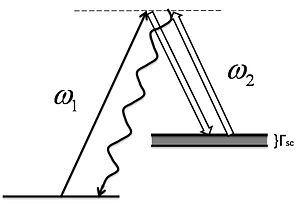

Let us assume large one-photon detuning, , weak probe and strong control field (we also define the two-photon detuning ).

In this limit analytic expressions for the absorption cross section for beam and the refractive index seen by beam exist, e.g. [Muller et al., PRA 56, 2385 (1997)]

The refractive index is given by:

where is the atomic density, .

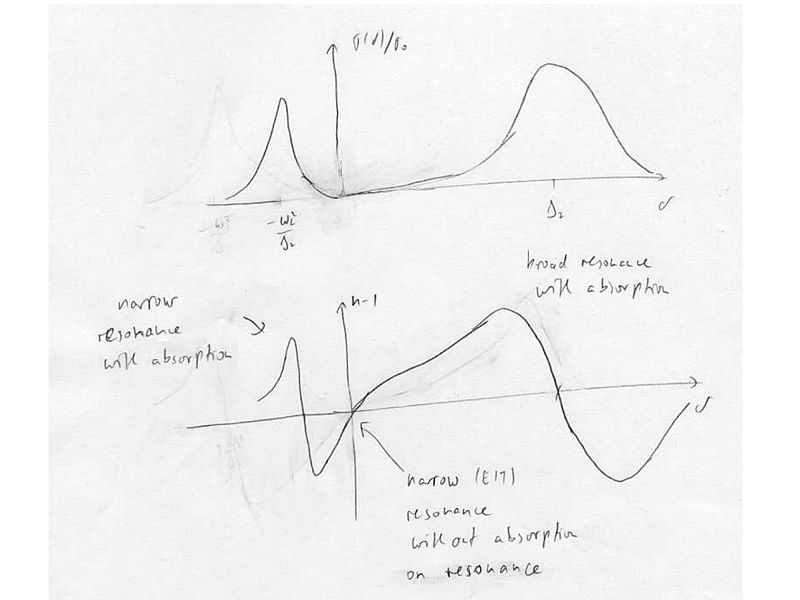

For zero ground-state linewidth (decoherence between the ground-states) where is the resonant cross-section, and .

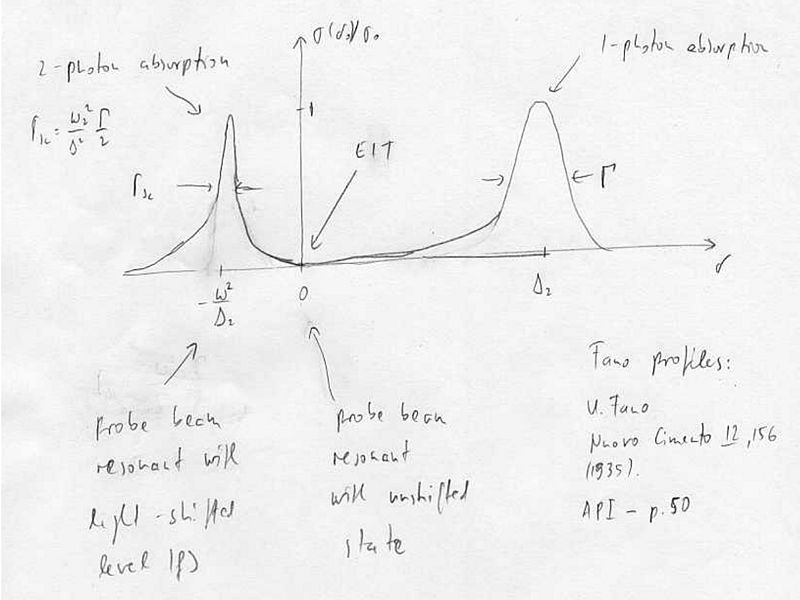

The absorption cross section for :

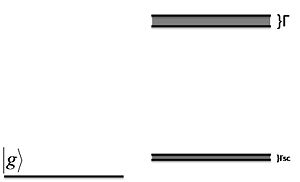

This is like a ground state coupling to one narrow and one wide excited state, except that there is EIT in between because both states decay to the same continuum.

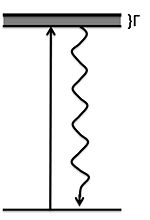

At , we have one-photon absorption, which is a two-photon scattering process:

At , two-photon absorption, which is (at least) four-photon scattering process:

For the EIT condition , there is no coupling to the excited state, and the refractive index is zero. In the vicinity of EIT, there is steep dispersion, resulting in a strong alteration of the group velocity of light slowing and stopping light.

Slow light, adiabatic changes of velocity of light

The group velocity of light in the presence of linear dispersion is given by [Harris and Hau, PRL 82, 4611 (1999)]

for light at frequency .

A strong linear dispersion with positive slope near EIT then corresponds to very slow light.

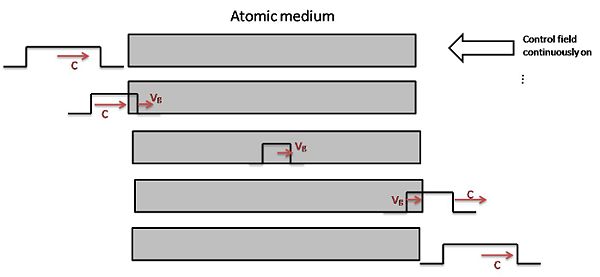

As , the electric field is unchanged so the power per area also remains unchanged.

Due to slowed group velocity, the pulse is compressed in the medium. As a consequence, the energy density is increased, and the light is partly in the form of an atomic excitation (coherent superposition of the ground states, although most of the energy is exchanged to the control field).

For sufficiently small , the velocity of light may be very small, down to a few m/s [L.V. Hau, S.E. Harris et al., Nature 397, 594 (1999)], as observed in a BEC. Reduced group velocity can also be observed in room-temperature experiment if the setup is Doppler free (co-propagating probe and control fields and ) (otherwise only a small velocity class satisfies the two-photon resonance condition).

If we change control field adiabatically while the pulse is inside the medium, we can coherently stop light, i.e. convert it into an atomic excitation or spin wave. With the reverse process we can then convert the stored spin-wave back into the original light field. The adiabatic conversion is made possible by the finite splitting between bright and dark states. In principle, all coherence properties and other (qm) features of the light are maintained, and it is possible to store non-classical states of light by mapping photon properties one-to-one onto quantized spin waves. We will learn more about these quanta called "dark-state polaritons" once we have introduced Dicke states. Is it possible to make use of EIT for, e.g. atom detection without absorption? Answer: no improvement for such linear processes. However: improvement for non-linear processes is possible.

Superradiance

Assume that two identical atoms, one in its ground and the other in its excited state, are placed within a distance of each other. What happens?

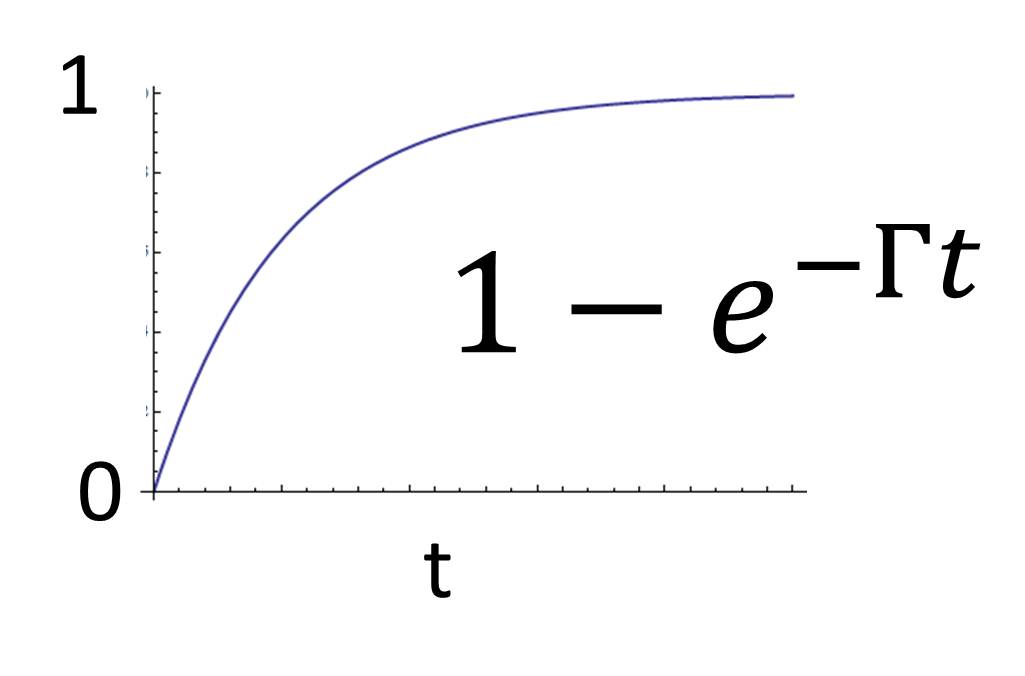

For a single atom we have, for the emission rate at time t is (product of the spontaneous emission rate and occupation probability). Thus, the emission probability to have emitted a photon by time t is

(eqtn:superradiance1)

What about two atoms? It turns out that the correct answer is

(eqtn:superradiance2)

(eqtn:superradiance3)

The photon is emitted with the same initial rate, but has only probability of being emitted at all! How can we understand this? The interaction Hamiltonian is (classically):

(eqtn:superradiance5)

In QED:

(eqtn:superradiance6)

with