Difference between revisions of "Tmp Lecture 26"

imported>Atsommer |

imported>Atsommer |

||

| (87 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

<br style="clear: both" /> | <br style="clear: both" /> | ||

== Superradiance, continued == | == Superradiance, continued == | ||

| − | + | Now we can write the initial state as: | |

| − | <math>| | + | <math>|ge,0>=\frac{1}{2}\underbrace{(|ge,0>+|eg,0>}_{\sqrt {2}|\mathrm{superradiant}>}+\underbrace{|ge,0>-|eg,0>)}_{\sqrt {2}|\mathrm{subradiant}>}</math> |

| − | + | where | |

| − | + | <math>|\mathrm{superradiant}>=\frac{1}{\sqrt {2}}(|ge,0>+|eg,0>)</math> | |

| − | <math> | + | <math>|\mathrm{subradiant}>=\frac{1}{\sqrt {2}}(|ge,0>-|eg,0>)</math> |

| + | |||

| + | and | ||

| + | |||

| + | <math><gg,1|V|\mathrm{superradiant}>=\sqrt {2}\hbar g; <gg,1|V|\mathrm{subradiant}>=0</math> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | <math>| | + | The initial state has a 50% probability to be the sub-radiant state, hence the system has a 50% probability of not decaying. The set of four states <math>|gg,0>,|ge,0>,|eg,0>,|ee,0></math> can be organized into a triplet and a singlet: |

| − | + | [[Image:twoAtomDicke.jpg]] | |

| − | + | The state <math>|ge>-|eg></math> is "dark" in that it does not decay under the action of the Hamiltonian V. The matrix elements between the states, indicated by arrows, are expressed in units of the single atom coupling <math>g=\frac{1}{\hbar }<e,0|V|g,1></math>. | |

| − | + | Just as we can identify the two-level system <math>|e>,|g></math>, with a (pseudo)spin <math>\frac{1}{2}</math>, we can identify the triplet and singlet states with <math>L=0,1</math>, and write | |

| − | + | <math>|L=1,M=1>=|ee></math> | |

| − | <math>|L=1,M= | + | <math>|L=1,M=0>=(|eg>+|ge>)/\sqrt{2}</math> |

| − | + | <math>|L=1,M=-1>=|gg></math> | |

| − | <math> | + | <math>|L=0,M=0>=(|ge>-|eg>)/\sqrt{2}</math> |

| − | + | Since V conserves parity (exchange of the two atoms), there is no coupling between singlet and triplet states. (This is no longer true when we consider spatially extended samples). | |

| − | + | == Supperradiance in N atoms == | |

| + | It is not difficult to generalize the formalism to more atoms | ||

| − | + | <math>V=-\vec{D}\cdot \vec{E}</math> with <math>\vec{D}=\Sigma^N_{i=1}\vec{d}_ i</math> | |

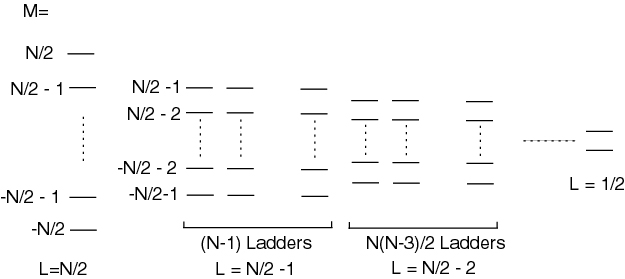

| − | + | The Dicke states, equivalent to the states obtained by summing N spin <math>\frac{1}{2}</math> particles, are | |

| − | + | [[Image:NAtomDicke.jpg]] | |

| − | + | Let us look at the leftmost (symmetric) ladder. Near the middle of the Dicke-ladder, <math>M\simeq 0</math>, the matrix element is | |

| − | < | + | <math> |

| − | </ | + | <V> \simeq \sqrt {\frac{N}{2}(\frac{N}{2}-1)}g\simeq N g. |

| − | + | </math> | |

| − | </ | + | The emission rate is proportional to <math>|<V>|^2\simeq N^2g^2</math>, i.e. the rate is quadratic in atom number. |

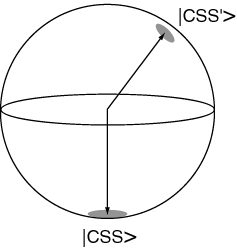

| − | Classically, that is not too surprising: we have N dipoles oscillating in phase, which corresponds to a dipole <math>D=Nd</math>, the emission is proportional to <math>D^2=N^2d^2</math>. However, the Dicke states have <math><D>=0</math> and nevertheless macroscopic emission. How do we see this? Bloch sphere, angular momentum representation | + | Classically, that is not too surprising: we have N dipoles oscillating in phase, which corresponds to a dipole <math>D=Nd</math>, the emission is proportional to <math>D^2=N^2d^2</math>. However, the Dicke states have <math><D>=0</math> and nevertheless macroscopic emission. How do we see this? In the Bloch sphere, for the angular momentum representation the coherent state <math>|L=N/2,M=-N/2>=|g...g></math> corresponds to all atoms in the ground state. |

| − | + | A field that symmetrically couples to all atoms (e.g. <math>\frac{\pi }{2},\pi </math> pulse) acts only within the completely symmetric Hilbert space <math>L=N/2</math>. This space consists of states like <math>(\cos \theta |e>+\sin \theta e^{i\phi }|g>)^ N</math>, corresponding to rotations of the state <math>|g...g></math> around some axis on the Bloch sphere. | |

| − | The | + | The states obtained by rotations of the state <math>|g...g></math> by symmetric operations that act on all individual atoms independently, i.e. of the form <math>|g>\rightarrow \cos \theta |e>+e^{i\phi }\sin \theta |g></math>, are called coherent spin states (CSS). They are represented by a vector on the Bloch sphere with uncertainties <math>\sqrt {\frac{L}{2}}</math> in directions perpendicular to the Bloch vector. |

| − | Image | + | [[Image:BlochSphereCSS2.jpg|center]] |

| − | + | If we prepare a system in the CSS corresponding to a slight angle away form <math>\theta =0</math> near <math>|e...e>=|L=N/2,M=N/2></math>, then classically it will obey the eqs of motion of an inverted pendulum, and fall down along the Bloch sphere. (This can be shown using the classical analogy with a field.) | |

| − | + | So what happens if we prepare the state <math>|M=+L>=|e...e></math>? Does it: | |

| − | + | a. evolve down along the Dicke ladder maintaining <math><D>=0</math> (but <math><D^2>\neq 0</math>)? | |

| − | + | b. fall like a Bloch vector along some angle chosen by vacuum fluctuations? | |

| − | Answer: there is no way of telling unless you prepare a specific experiment. If we detect (with unity quantum efficiency) the emitted photons, | + | Answer: there is no way of telling unless you prepare a specific experiment. If we detect (with unity quantum efficiency) the emitted photons, then each detection projects the system one step down along the Dicke ladder, and <math><D>=0</math>. |

| − | If we measure the phase of the emitted light, say with some heterodyne technique, then we find that the system evolves as a Bloch state. | + | If we measure the phase of the emitted light, say with some heterodyne technique, then we find that the system evolves as a Bloch state. |

| − | |||

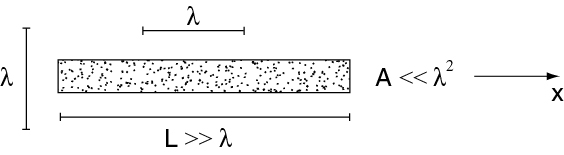

== Dicke states of extended samples == | == Dicke states of extended samples == | ||

Consider an elongated atomic sample | Consider an elongated atomic sample | ||

| − | Image | + | [[Image:26_ExtendedDicke.jpg]] |

such that a preferential mode (along x) is defined. Then we can define Dicke states with respect to that mode as | such that a preferential mode (along x) is defined. Then we can define Dicke states with respect to that mode as | ||

| − | <math>|L,M=-L>=|g...g></math> | + | <math>|L,M=-L>=|g...g></math> |

| − | + | <math>|L,M=-L+1>=\frac{1}{\sqrt {N}}(e^{i k x_1}|eg...g>+e^{ikx_2}|geg...>+...+e^{ikx_N}|g...ge>)</math> | |

| + | |||

| + | <math>|L,M=-L+2>=\frac{\sqrt {2}}{\sqrt {N(N-1)}}|e^{ik x_1}e^{ik x_ 2}|eeg...g>+e^{ik x_1}e^{ikx_ 2}|egeg...>+...</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | etc. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Then one can easily see that the phase factors are such that the interaction Hamiltonian | ||

| + | |||

| + | <math>V=\Sigma _ i\vec{d_ i}\cdot \vec{E}(\vec{x_ i})=\Sigma _ i\vec{d}\cdot \vec{E}_0e^{i\kappa x_ i}</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | is such that the Dicke ladder has the same couplings as before, i.e. superradiance occurs. However, emission along a direction other than the preferred mode now leads to diagonal couplings between the Dicke ladders , since emission along some other direction with operator <math>e^{i\vec{k}\cdot \vec{r}}</math> does not preserve the symmetry of the state with respect to permutations of the atoms. However, if the atom number along the preferred direction is large enough, superradiance still occurs. The condition for <math>A\ll\lambda^2</math> is <math>N\geq 2</math>, but for <math>A>\lambda^2</math> the condition is <math>\frac{N\lambda ^2}{A}>1</math>. This is exactly the condition for sufficient optical gain in an inverted system for optical amplification (lasing) to occur, since <math>\lambda ^2</math> is the stimulated emission cross section for an atom in <math>|e></math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Observation in a BEC, in multimode optical cavities. | ||

| − | |||

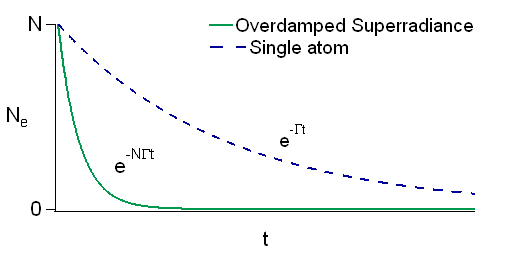

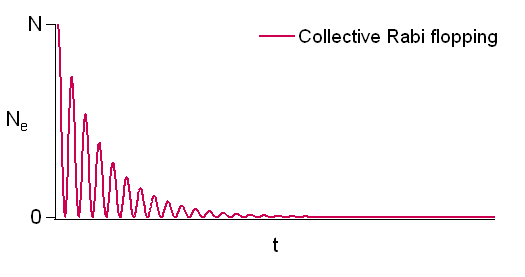

== Oscillating and overdamped regimes of superradiance == | == Oscillating and overdamped regimes of superradiance == | ||

| − | The photon leaves the sample in a time <math>\frac{L}{c}</math> | + | The photon leaves the sample in a time <math>\frac{L}{c}</math>. If <math>\sqrt{N}g<\frac{c}{L}</math>, then the damping is faster than Rabi flopping, and we are in the rate equation limit where the emission proceeds as <math>\frac{(\sqrt {N}g)^2}{c/L}=\frac{Ng^2L}{c}</math>, rather than as emission by independent atoms that would decay as <math>\frac{g^2}{c/L}</math>. If <math>\sqrt {N}g>\frac{c}{L}</math>, then Rabi flopping occurs during the decay. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | [[Image:DickeDecay.jpg]] | |

| + | [[Image:DickeRabi4.jpg]] | ||

| − | + | Note:<math>\Gamma = g^2L/C</math>. | |

| − | |||

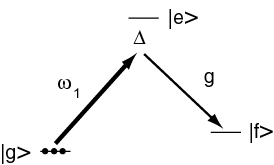

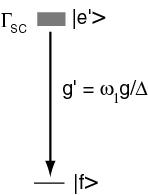

== Raman Superradiance == | == Raman Superradiance == | ||

| − | Image | + | [[Image:26_RamanSuperradiance.jpg]] |

In the limit of large <math>\Delta </math> and low saturation <math>\omega _1\ll \Delta </math>, we can eliminate the excited state and have an effective system. | In the limit of large <math>\Delta </math> and low saturation <math>\omega _1\ll \Delta </math>, we can eliminate the excited state and have an effective system. | ||

| − | Image | + | [[Image:26_RamanEffectiveSystem.jpg|center]] |

| − | <math> | + | <math>\Gamma_{sc}=\frac{\omega _1^2}{\Delta ^2}\frac{r}{2}</math> |

| − | We can now adjust the linewidth <math> | + | We can now adjust the linewidth <math>\Gamma_{sc}</math> via <math>\omega _1</math> and also make the excited state <math>|e'></math> suddenly stable by turning off <math>\omega _1</math>. In fact we can switch ground and excited states by applying a laser beam on the other Raman leg instead. |

<br style="clear: both" /> | <br style="clear: both" /> | ||

| − | |||

| − | Image | + | == Storing light, catching photons == |

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:26_StoringLight.jpg]] | ||

When we consider a quantized field on the <math>|g>\rightarrow |e></math> transition, there is a family of dark states, corresponding to <math>n=0,1,2,...</math> excitations | When we consider a quantized field on the <math>|g>\rightarrow |e></math> transition, there is a family of dark states, corresponding to <math>n=0,1,2,...</math> excitations | ||

| − | <math>|D,n>=\Sigma ^ n_{ | + | <math>|D,n>=\Sigma ^ n_{k=0}\sqrt {\frac{n!}{k!(n-k)!}}\frac{(-g)^{k }N^{\frac{k }{2}}\Omega ^{n-k }}{(Ng^2+\Omega ^2)^{\frac{n}{2}}}|n-k >_{\mathrm{photons}}|L=\frac{N}{2},M=-L+k ></math> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | (Lukin, Yelin, and Fleischhauer PRL 84, 4233 (2000)). | |

| − | + | When <math>\Omega \gg Ng^2</math>, these states are purely photonic. When <math>\omega \ll Ng^2</math>, these states are purely atomic excitations. | |

| − | + | <math> | |

| + | \Omega \gg Ng^2 :|D,n> \rightarrow |n>_{\mathrm{photons}}|L,M=-L>_{\mathrm{atoms}} | ||

| + | </math> | ||

| − | < | + | <math>\Omega \ll Ng^2 : |0>_{\mathrm{photons}}|L,M=-L+n>_{\mathrm{atoms}}</math> |

| − | = | + | In general, these excitations n=0,1,2,... are called dark state polaritons. They are a mixture of photonic excitations and spin-wave excitations. |

| − | + | By adiabatically changing <math>\Sigma \rightarrow 0</math> after the pulse has entered the medium, we can map any photonic state <math>|\psi >_{\mathrm{photon}}=\Sigma c_i|i>_{\mathrm{photon}}</math> onto a spin wave, store it and map it back onto a light-field by turning on the coupling laser <math>\Omega </math> again. | |

Latest revision as of 06:10, 3 May 2010

Lecture XXVI

Contents

Superradiance, continued

Now we can write the initial state as:

where

and

The initial state has a 50% probability to be the sub-radiant state, hence the system has a 50% probability of not decaying. The set of four states can be organized into a triplet and a singlet:

The state is "dark" in that it does not decay under the action of the Hamiltonian V. The matrix elements between the states, indicated by arrows, are expressed in units of the single atom coupling .

Just as we can identify the two-level system , with a (pseudo)spin , we can identify the triplet and singlet states with , and write

Since V conserves parity (exchange of the two atoms), there is no coupling between singlet and triplet states. (This is no longer true when we consider spatially extended samples).

Supperradiance in N atoms

It is not difficult to generalize the formalism to more atoms

with

The Dicke states, equivalent to the states obtained by summing N spin particles, are

Let us look at the leftmost (symmetric) ladder. Near the middle of the Dicke-ladder, , the matrix element is The emission rate is proportional to , i.e. the rate is quadratic in atom number.

Classically, that is not too surprising: we have N dipoles oscillating in phase, which corresponds to a dipole , the emission is proportional to . However, the Dicke states have and nevertheless macroscopic emission. How do we see this? In the Bloch sphere, for the angular momentum representation the coherent state corresponds to all atoms in the ground state.

A field that symmetrically couples to all atoms (e.g. pulse) acts only within the completely symmetric Hilbert space . This space consists of states like , corresponding to rotations of the state around some axis on the Bloch sphere.

The states obtained by rotations of the state by symmetric operations that act on all individual atoms independently, i.e. of the form , are called coherent spin states (CSS). They are represented by a vector on the Bloch sphere with uncertainties in directions perpendicular to the Bloch vector.

If we prepare a system in the CSS corresponding to a slight angle away form near , then classically it will obey the eqs of motion of an inverted pendulum, and fall down along the Bloch sphere. (This can be shown using the classical analogy with a field.)

So what happens if we prepare the state ? Does it:

a. evolve down along the Dicke ladder maintaining (but )?

b. fall like a Bloch vector along some angle chosen by vacuum fluctuations?

Answer: there is no way of telling unless you prepare a specific experiment. If we detect (with unity quantum efficiency) the emitted photons, then each detection projects the system one step down along the Dicke ladder, and .

If we measure the phase of the emitted light, say with some heterodyne technique, then we find that the system evolves as a Bloch state.

Dicke states of extended samples

Consider an elongated atomic sample

such that a preferential mode (along x) is defined. Then we can define Dicke states with respect to that mode as

etc.

Then one can easily see that the phase factors are such that the interaction Hamiltonian

is such that the Dicke ladder has the same couplings as before, i.e. superradiance occurs. However, emission along a direction other than the preferred mode now leads to diagonal couplings between the Dicke ladders , since emission along some other direction with operator does not preserve the symmetry of the state with respect to permutations of the atoms. However, if the atom number along the preferred direction is large enough, superradiance still occurs. The condition for is , but for the condition is . This is exactly the condition for sufficient optical gain in an inverted system for optical amplification (lasing) to occur, since is the stimulated emission cross section for an atom in .

Observation in a BEC, in multimode optical cavities.

Oscillating and overdamped regimes of superradiance

The photon leaves the sample in a time . If , then the damping is faster than Rabi flopping, and we are in the rate equation limit where the emission proceeds as , rather than as emission by independent atoms that would decay as . If , then Rabi flopping occurs during the decay.

Note:.

Raman Superradiance

In the limit of large and low saturation , we can eliminate the excited state and have an effective system.

We can now adjust the linewidth via and also make the excited state suddenly stable by turning off . In fact we can switch ground and excited states by applying a laser beam on the other Raman leg instead.

Storing light, catching photons

When we consider a quantized field on the transition, there is a family of dark states, corresponding to excitations

(Lukin, Yelin, and Fleischhauer PRL 84, 4233 (2000)).

When , these states are purely photonic. When , these states are purely atomic excitations.

In general, these excitations n=0,1,2,... are called dark state polaritons. They are a mixture of photonic excitations and spin-wave excitations.

By adiabatically changing after the pulse has entered the medium, we can map any photonic state onto a spin wave, store it and map it back onto a light-field by turning on the coupling laser again.