Difference between revisions of "Casimir interaction"

imported>Ketterle |

imported>Ketterle |

||

| Line 29: | Line 29: | ||

INSERT IMAGE 1 | INSERT IMAGE 1 | ||

| + | For a given m, the density of modes is linear in <math>\omega</math>. For the total density of modes, we have to sum up all these linear mode densities: | ||

| + | ::[[Image:Casimir_interaction-casimir-mode-density.png|thumb|510px|none|]] | ||

| − | + | The sum of those linear curves results in a trapezoid, approximating the parabolic density of modes in 3D. It is exactly the difference between the trapezoidal and parabolic densities of modes, which gives rise to the Casimir energy. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | More analytically, we find | |

| − | + | INSERT IMAGE 2 | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

We can now use these expressions to get the total zero point energy in | We can now use these expressions to get the total zero point energy in | ||

| Line 55: | Line 48: | ||

\,. | \,. | ||

\end{align}</math> | \end{align}</math> | ||

| − | The integrand diverges, which is unphysical. | + | The integrand diverges, which is unphysical. We have to introduce a high |

| − | frequency cutoff needs | + | frequency cutoff needs. Since we will compare the effect of two different boundary conditions on the |

| − | + | zero point energy, we will be subtracting two integrals, and the divergent parts of the integrals will cancel anyway. Physically, we can argue that the metallic boundary condition is no longer valid for X rays when the plates become transparent. | |

| − | zero point energy, | + | |

| − | + | Instead of a hard cutoff, we multiply the integrand by a convergence term <math>e^{-\lambda \omega/c}</math>, and find | |

:<math>\begin{array}{rcl} | :<math>\begin{array}{rcl} | ||

W(L) = {\rm const.} + \frac{a^2\hbar}{2\pi c^2}\sum_m I_m | W(L) = {\rm const.} + \frac{a^2\hbar}{2\pi c^2}\sum_m I_m | ||

\end{array}</math> | \end{array}</math> | ||

with | with | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | INSERT IMAGE 3 | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | and | |

| + | |||

| + | INSERT IMAGE 4 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Finally, | ||

:<math>\begin{array}{rcl} | :<math>\begin{array}{rcl} | ||

\sum_m I_m = \frac{c^3\pi}{L} \frac{\partial^2}{\partial\lambda^2} | \sum_m I_m = \frac{c^3\pi}{L} \frac{\partial^2}{\partial\lambda^2} | ||

| Line 74: | Line 71: | ||

\end{array}</math> | \end{array}</math> | ||

This can be expanded about <math>x=0</math>, where <math>x=\pi \lambda/L</math>, | This can be expanded about <math>x=0</math>, where <math>x=\pi \lambda/L</math>, | ||

| − | corresponding to letting <math>\lambda\rightarrow 0</math>. | + | corresponding to letting <math>\lambda\rightarrow 0</math>, i.e. the limit of infinite cutoff frequency. |

We want to compare mode densities, so let us embed our capacitor of | We want to compare mode densities, so let us embed our capacitor of | ||

Revision as of 01:59, 27 April 2009

Semiclassical derivation of the Casimir force

Today, we will look at a completely different derivation of the Casimir force, based on zero-point fluctuations. Photon exchange and zero-point fluctuations are two equivalent ways of deriving Casimir forces. We will discuss this again at the end of this section.

Here we show that the Casimir force can be understand from the spectrum of classical fields between two conducting plates. Once we have all the electromagnetic modes, we can multiply each by then sum to get the zero point energy of the field. We will follow a derivation given by Haroche (Les Houches summer school), and for details of the modes between two parallel plates we refer to Jackson.

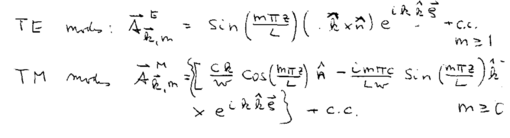

Consider two parallel metallic plates, separated by distance . Due to the boundary condition that the electric field must be zero at and , where describes the coordinate perpendicular to the plates. We have a discrete set of mode which can be distinguished as TE and TM modes. Their vector potentials are:

Parallel to the plates, we have propagating modes which can assume any wavevector components for free space propagation in two dimensions.

We want to count these modes, and obtain the density of states. Consider the number of modes with momentum between and . In a waveguide, the total wavenumber is . Thus, for each standing wave, there is a continuum, with wavenumber starting at the base value given by the standing wave, and increasing continuously from there. The number of modes between k and k+dk for a given m and k is

INSERT IMAGE 1

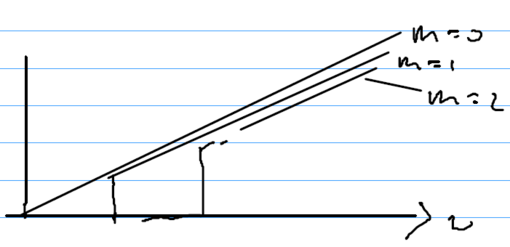

For a given m, the density of modes is linear in . For the total density of modes, we have to sum up all these linear mode densities:

The sum of those linear curves results in a trapezoid, approximating the parabolic density of modes in 3D. It is exactly the difference between the trapezoidal and parabolic densities of modes, which gives rise to the Casimir energy.

More analytically, we find

INSERT IMAGE 2

We can now use these expressions to get the total zero point energy in volume . We get

The integrand diverges, which is unphysical. We have to introduce a high frequency cutoff needs. Since we will compare the effect of two different boundary conditions on the zero point energy, we will be subtracting two integrals, and the divergent parts of the integrals will cancel anyway. Physically, we can argue that the metallic boundary condition is no longer valid for X rays when the plates become transparent.

Instead of a hard cutoff, we multiply the integrand by a convergence term , and find

with

INSERT IMAGE 3

and

INSERT IMAGE 4

Finally,

This can be expanded about , where , corresponding to letting , i.e. the limit of infinite cutoff frequency.

We want to compare mode densities, so let us embed our capacitor of spacing within a bigger capacitor of spacing . We compute , and drop terms independent of . This gives

This gives the Casimir potential,

The Casimir force, given as a pressure betwen the two plates, is thus

Such a derivation can also be done for models other than two metallic plates. You can also derive in the same way the Casimir potential for a metal plate interacting with a single atom. This is done by recognizing that the atom is a dielectric medium, which modifies the field density near the metal plate. Similarly, for the atom-atom interaction, the two atoms can be put inside a large box; the two atoms act as tiny dielectric media, which change the field density in the box, also leading to a Casimiar potential.

Interpretation of the Casimir Potential

The interpretation of the Casimiar potential has become quite interesting recently because of the realization that the origin of dark matter may arise from the physical reality of zero point energy. Such zero point energy could concievably give rise to a gravitational force. However, the numerical value of the potential strength obtained is hundreds of orders of magnitude off from what would be needed to be consistent with the observed value of the cosmological constant. Nevertheless, there is much to be learned from the different derivations of the Casimiar force.

Let us discuss the two derivations we've seen. One way was to use two metallic plates and to count the number of modes inbetween them. Another way was to consider all the atoms in two parallel walls, and allow the atoms to exchange virtual photons. Robert Jaffe has written a beautiful treatise (Phys. Rev. D) discussing these two viewpoints, and shows these are equivalent, and that one does not even need, in principle, the concept of zero point energies. The conclision is that you should not use the existence of the Casimir force as evidence of zero point energy.

Note that the Casimir force is independent of atomic properties, in the limit that the fine structure constant is very large. If you take the limit , then the atomic radius , in which case the Casimir force also goes to zero. Thus, by taking our material to be metallic, we are assuming that the fine structure constant is large. For distances as small as m, it is sufficient for to be able to well approximate the resulting force as being independent of atomic properties.

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}W(L)&=\int _{0}^{\infty }{\frac {\hbar \omega }{2}}\rho (\omega )d\omega \\&={\frac {a^{2}\hbar }{4\pi c^{2}}}\left[{\int _{0}^{\infty }\omega ^{2}d\omega +2\sum _{m=1}^{\infty }\int _{m\pi c/L}^{\infty }\omega ^{2}d\omega }\right]\,.\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/fdac3bf637c4c48f14709650136e42756e5526a5)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{array}{rcl}\sum _{m}I_{m}={\frac {c^{3}\pi }{L}}{\frac {\partial ^{2}}{\partial \lambda ^{2}}}\left[{{\frac {1}{(\pi \lambda /L)}}{\frac {1}{e^{\pi \Lambda /L}-1}}}\right]\end{array}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/1028f463088a7c7c3c4378e7cd45286d958f80fe)