Difference between revisions of "Quantum control and trapped ions"

imported>Wikibot m (New page: = Ion traps and quantum information = == Quantum control and trapped ions == Laser cooling is a process which allows atoms to be brought to their motional ground state, or into a condensa...) |

imported>Ichuang (Added tag: 'QCQI') |

||

| (4 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

Laser cooling is a process which allows atoms to be brought to their | Laser cooling is a process which allows atoms to be brought to their | ||

motional ground state, or into a condensate state. A natural | motional ground state, or into a condensate state. A natural | ||

| Line 10: | Line 7: | ||

example of this area of inquiry, focused on creation of arbitrary | example of this area of inquiry, focused on creation of arbitrary | ||

states of motion of a single ion. | states of motion of a single ion. | ||

| + | |||

=== Quantum control in perspective === | === Quantum control in perspective === | ||

Quantum control has many applications in modern physics. Chemical | Quantum control has many applications in modern physics. Chemical | ||

| Line 23: | Line 21: | ||

states and entanglement, for precision metrology and studies of | states and entanglement, for precision metrology and studies of | ||

fundamental quantum physics. | fundamental quantum physics. | ||

| + | |||

The concept of quantum control builds on the extensive field of | The concept of quantum control builds on the extensive field of | ||

classical control of dynamical systems. Classical control theory | classical control of dynamical systems. Classical control theory | ||

| Line 35: | Line 34: | ||

acting back on the system (eg lasers): | acting back on the system (eg lasers): | ||

::[[Image:Quantum_control_and_trapped_ions-qcontrol-model.png|thumb|400px|none|]] | ::[[Image:Quantum_control_and_trapped_ions-qcontrol-model.png|thumb|400px|none|]] | ||

| − | + | ||

Two main control objectives, in this context, are (1) state | Two main control objectives, in this context, are (1) state | ||

engineering: steering the quantum system into an arbitrary quantum | engineering: steering the quantum system into an arbitrary quantum | ||

state, and (2) process engineering: realizing an arbitrary unitary | state, and (2) process engineering: realizing an arbitrary unitary | ||

transform on the quantum system. | transform on the quantum system. | ||

| + | |||

Many general strategies exist for achieving these quantum control | Many general strategies exist for achieving these quantum control | ||

objectives. Broadly, these all involve some modification of the | objectives. Broadly, these all involve some modification of the | ||

system Hamiltonian <math>H_{sys}</math> using control Hamiltonian <math>H_{ctrl} = | system Hamiltonian <math>H_{sys}</math> using control Hamiltonian <math>H_{ctrl} = | ||

\sum_k c(t) H_k^{ctrl}</math>. Strategies include: | \sum_k c(t) H_k^{ctrl}</math>. Strategies include: | ||

| − | + | ||

* Open loop control: no feedback, state <math>|\psi(t=0){\rangle}</math> is known | * Open loop control: no feedback, state <math>|\psi(t=0){\rangle}</math> is known | ||

| − | * Closed loop control: feedback based on classical | + | * Closed loop control: feedback based on classical measurement record, with either weak measurements and continuous |

| − | measurement record, with either weak measurements and continuous | + | feedback, or strong measurement and feedback at discrete times, or adaptive measurements changed based on classical record |

| − | feedback, or strong measurement and feedback at discrete times, or | + | * Coherent control: use of an ancilla quantum system in place of the measurement and actuator, with controllable coupling to the system under control |

| − | adaptive measurements changed based on classical record | + | * Learning control: applied to ensembles, with feedforward control in place of feedback to systems individually |

| − | * Coherent control: use of an ancilla quantum system in | + | |

| − | place of the measurement and actuator, with controllable coupling to | ||

| − | the system under control | ||

| − | * Learning control: applied to ensembles, with feedforward | ||

| − | control in place of feedback to systems individually | ||

| − | |||

The presence of interactions with an environment significantly | The presence of interactions with an environment significantly | ||

complicates quantum control. Also, in strong contrast to classical | complicates quantum control. Also, in strong contrast to classical | ||

| Line 70: | Line 65: | ||

will not improve controllability. For example, one basic theorem in | will not improve controllability. For example, one basic theorem in | ||

quantum control is the following: | quantum control is the following: | ||

| − | + | <blockquote> | |

Theorem: A (closed) quantum system with Hamiltonian <math>H_{sys}</math>, | Theorem: A (closed) quantum system with Hamiltonian <math>H_{sys}</math>, | ||

in Hilbert space <math>V_H</math>, with controls <math>\{C_k(t) H_k^{ctrl}\}</math>, is {\em | in Hilbert space <math>V_H</math>, with controls <math>\{C_k(t) H_k^{ctrl}\}</math>, is {\em | ||

controllable} iff any Hamiltonian on <math>V_H</math> can be generated in the | controllable} iff any Hamiltonian on <math>V_H</math> can be generated in the | ||

closure of <math>\{H_{sys},H_k^{ctrl}\}</math>. | closure of <math>\{H_{sys},H_k^{ctrl}\}</math>. | ||

| − | + | </blockquote> | |

| − | + | ||

In this theorem, closure refers to the completion of the algebra | In this theorem, closure refers to the completion of the algebra | ||

of the Hamiltonians by commuting all given Hamiltonians with each | of the Hamiltonians by commuting all given Hamiltonians with each | ||

| Line 83: | Line 78: | ||

terms, then the system is controllable. Some examples are helpful in | terms, then the system is controllable. Some examples are helpful in | ||

illustrating this theorem. | illustrating this theorem. | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | * Example 1: <math>H_{sys} = \hbar\omega_0 \sigma_z</math>, <math>H_{ctrl} = | + | * Example 1: <math>H_{sys} = \hbar\omega_0 \sigma_z</math>, <math>H_{ctrl} = \Omega(t) \sigma_x</math>. This system is controllable, because any <math>H=a\sigma_x + b\sigma_y + c\sigma_z</math> can be generated by <math>H_{sys}</math> and <math>H_{ctrl}</math>, since <math>[\sigma_x,\sigma_z] = -2i\sigma_y</math>. |

| − | \Omega(t) \sigma_x</math>. This system is controllable, because any | + | * Example 2: <math>H_{sys} = \hbar\omega_0 \sigma_z</math>, <math>H_{ctrl} = \Omega(t) \sigma_z</math>. This system is not controllable. |

| − | <math>H=a\sigma_x + b\sigma_y + c\sigma_z</math> can be generated by <math>H_{sys}</math> | + | * Example 3: <math>H_{sys} = \hbar\nu a^\dagger a</math>, <math>H_{ctrl} = \alpha^* a + \alpha a^\dagger </math>. This system is not controllable. |

| − | and <math>H_{ctrl}</math>, since <math>[\sigma_x,\sigma_z] = -2i\sigma_y</math>. | + | * Example 4: <math>H_{sys} = \hbar\omega_0 \sigma_z + \hbar\nu a^\dagger a</math>, <math>H_{ctrl} = \Omega(t) \sigma_x (a+ a^\dagger )</math>. This system is not controllable. |

| − | * Example 2: <math>H_{sys} = \hbar\omega_0 \sigma_z</math>, <math>H_{ctrl} = | + | * Example 5: <math>H_{sys} = \hbar\omega_0 \sigma_z + \hbar\nu a^\dagger a</math>, <math>H_{ctrl} = \Omega(t) \cos[\eta (a+ a^\dagger )-\omega t]</math> (<math>\Omega</math> and <math>\omega</math> are the control parameters). This system {\em is} controllable. |

| − | \Omega(t) \sigma_z</math>. This system is not controllable. | + | |

| − | * Example 3: <math>H_{sys} = \hbar\nu a^\dagger a</math>, <math>H_{ctrl} = | ||

| − | \alpha^* a + \alpha a^\dagger </math>. This system is not controllable. | ||

| − | * Example 4: <math>H_{sys} = \hbar\omega_0 \sigma_z + \hbar\nu | ||

| − | a^\dagger a</math>, <math>H_{ctrl} = \Omega(t) \sigma_x (a+ a^\dagger )</math>. This system is | ||

| − | not controllable. | ||

| − | * Example 5: <math>H_{sys} = \hbar\omega_0 \sigma_z + \hbar\nu | ||

| − | a^\dagger a</math>, <math>H_{ctrl} = \Omega(t) \cos[\eta (a+ a^\dagger )-\omega t]</math> | ||

| − | (<math>\Omega</math> and <math>\omega</math> are the control parameters). This system {\em | ||

| − | is} controllable. | ||

| − | |||

The last of these examples describes a single trapped ion, controlled | The last of these examples describes a single trapped ion, controlled | ||

by incident laser light, as we shall now explore. | by incident laser light, as we shall now explore. | ||

| + | |||

=== Motional state control: a trapped ion === | === Motional state control: a trapped ion === | ||

| + | |||

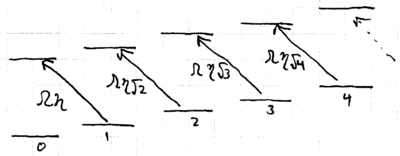

Let us consider quantum control of a single trapped ion, modeled by a | Let us consider quantum control of a single trapped ion, modeled by a | ||

system of photon + atom + phonon. We will let the photon light field | system of photon + atom + phonon. We will let the photon light field | ||

| Line 108: | Line 95: | ||

energy eigenstates of the atom + phonon system may be depicted as a ladder: | energy eigenstates of the atom + phonon system may be depicted as a ladder: | ||

::[[Image:Quantum_control_and_trapped_ions-qcontrol-eeig.png|thumb|400px|none|]] | ::[[Image:Quantum_control_and_trapped_ions-qcontrol-eeig.png|thumb|400px|none|]] | ||

| − | |||

And as we have previously seen, the interaction Hamiltonian is | And as we have previously seen, the interaction Hamiltonian is | ||

:<math> | :<math> | ||

| Line 147: | Line 133: | ||

the energy spectrum at the recoil energy, causing the whole atom and | the energy spectrum at the recoil energy, causing the whole atom and | ||

trap to recoil instead of just the atom. | trap to recoil instead of just the atom. | ||

| + | |||

When the laser is detuned to <math>\omega_L\approx \omega_{eg}-\nu</math>, the | When the laser is detuned to <math>\omega_L\approx \omega_{eg}-\nu</math>, the | ||

red sideband is excited, giving the approximate Hamiltonian | red sideband is excited, giving the approximate Hamiltonian | ||

| Line 168: | Line 155: | ||

coupling states on the ladder as: | coupling states on the ladder as: | ||

::[[Image:Quantum_control_and_trapped_ions-qcontrol-antijcham.png|thumb|400px|none|]] | ::[[Image:Quantum_control_and_trapped_ions-qcontrol-antijcham.png|thumb|400px|none|]] | ||

| − | + | ||

Given that pairs of levels are coupled independently by the sideband | Given that pairs of levels are coupled independently by the sideband | ||

excitation, it is convenient to define Rabi frequencies for these | excitation, it is convenient to define Rabi frequencies for these | ||

pairs, <math>\Omega_n = \eta \Omega\sqrt{n+1}</math>. | pairs, <math>\Omega_n = \eta \Omega\sqrt{n+1}</math>. | ||

| − | === Fock, coherent, and Schr | + | |

| + | === Fock, coherent, and Schrödinger cat states of an ion === | ||

| + | |||

Let us now turn to the challenge of creating specific motional states | Let us now turn to the challenge of creating specific motional states | ||

of a trapped ion, using the given carrier and sideband Hamiltonians. | of a trapped ion, using the given carrier and sideband Hamiltonians. | ||

First, note that the state <math>|g,0{\rangle}</math> can be prepared using Doppler | First, note that the state <math>|g,0{\rangle}</math> can be prepared using Doppler | ||

cooling, followed by resolved sideband cooling. | cooling, followed by resolved sideband cooling. | ||

| + | |||

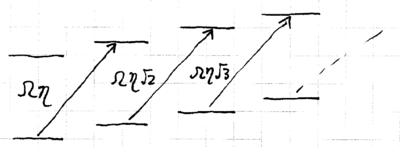

What experimental signature attests to the ion being in the <math>|g,0{\rangle}</math> | What experimental signature attests to the ion being in the <math>|g,0{\rangle}</math> | ||

state? One ion used in experiments is <math>^{138}</math>Ba<math>^+</math>, which has three | state? One ion used in experiments is <math>^{138}</math>Ba<math>^+</math>, which has three | ||

| Line 185: | Line 175: | ||

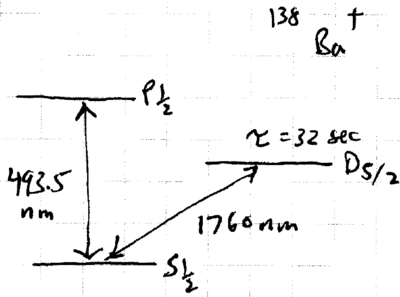

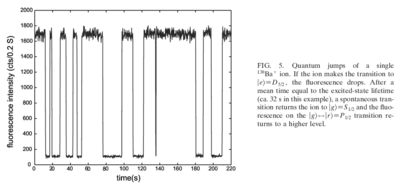

the ion is weakly excited at <math>1760</math> nm: | the ion is weakly excited at <math>1760</math> nm: | ||

::[[Image:Quantum_control_and_trapped_ions-fig1-quantum-jumps.png|thumb|400px|none|]] | ::[[Image:Quantum_control_and_trapped_ions-fig1-quantum-jumps.png|thumb|400px|none|]] | ||

| − | + | (this and other data shown here taken from {\em Quantum | |

dynamics of single trapped ions}, by Leibfried, Blatt, Monroe, and | dynamics of single trapped ions}, by Leibfried, Blatt, Monroe, and | ||

Wineland, Rev. Mod. Phys., v75, p281, 2003). The statistics of | Wineland, Rev. Mod. Phys., v75, p281, 2003). The statistics of | ||

| − | such jumps | + | such jumps provides very sensitive information about the internal |

state of an ion. Specifically, as the narrow S-D frequency laser is | state of an ion. Specifically, as the narrow S-D frequency laser is | ||

scanned through the sideband frequencies, a spectrum such as this is | scanned through the sideband frequencies, a spectrum such as this is | ||

| Line 208: | Line 198: | ||

This is a sideband spectrum been obtained after resolved sideband cooling: | This is a sideband spectrum been obtained after resolved sideband cooling: | ||

::[[Image:Quantum_control_and_trapped_ions-fig2-sideband-cooling-result.png|thumb|400px|none|]] | ::[[Image:Quantum_control_and_trapped_ions-fig2-sideband-cooling-result.png|thumb|400px|none|]] | ||

| + | |||

==== Fock states ==== | ==== Fock states ==== | ||

| + | |||

Now consider the challenge of creating not just <math>|g,0{\rangle}</math>, but rather a | Now consider the challenge of creating not just <math>|g,0{\rangle}</math>, but rather a | ||

nonzero Fock state of the ion motion, <math>|g,n{\rangle}</math>. This can be realized, | nonzero Fock state of the ion motion, <math>|g,n{\rangle}</math>. This can be realized, | ||

in principle, by applying a sequence of <math>\pi</math> pulses on the blue sideband: | in principle, by applying a sequence of <math>\pi</math> pulses on the blue sideband: | ||

::[[Image:Quantum_control_and_trapped_ions-qcontrol-fock.png|thumb|400px|none|]] | ::[[Image:Quantum_control_and_trapped_ions-qcontrol-fock.png|thumb|400px|none|]] | ||

| − | + | ||

The unitary transformation effected by laser on the blue sideband | The unitary transformation effected by laser on the blue sideband | ||

perform rotations on the two-level manifolds which the excitations | perform rotations on the two-level manifolds which the excitations | ||

| Line 232: | Line 224: | ||

<math>n</math> increases. Odd numbered <math>n</math> Fock states can be created by | <math>n</math> increases. Odd numbered <math>n</math> Fock states can be created by | ||

inserting an additional carrier <math>\pi</math> pulse. | inserting an additional carrier <math>\pi</math> pulse. | ||

| + | |||

Experimentally, the signature of having created <math>|g,n{\rangle}</math> can be | Experimentally, the signature of having created <math>|g,n{\rangle}</math> can be | ||

obtained by measuring the Rabi frequency of the sideband, since | obtained by measuring the Rabi frequency of the sideband, since | ||

| Line 242: | Line 235: | ||

<math>|g{\rangle}</math>. This is known as shelving: | <math>|g{\rangle}</math>. This is known as shelving: | ||

::[[Image:Quantum_control_and_trapped_ions-qcontrol-shelving.png|thumb|400px|none|]] | ::[[Image:Quantum_control_and_trapped_ions-qcontrol-shelving.png|thumb|400px|none|]] | ||

| − | + | ||

Shelving allows measurement of <math>P_g</math> with fidelity better than | Shelving allows measurement of <math>P_g</math> with fidelity better than | ||

<math>99.9\%</math> is many ions, such as <math>^9</math>Be<math>^+</math>, in a time as short as <math>100</math> | <math>99.9\%</math> is many ions, such as <math>^9</math>Be<math>^+</math>, in a time as short as <math>100</math> | ||

| Line 249: | Line 242: | ||

states has been verified experimentally: | states has been verified experimentally: | ||

::[[Image:Quantum_control_and_trapped_ions-fig3-fock-state-result.png|thumb|400px|none|]] | ::[[Image:Quantum_control_and_trapped_ions-fig3-fock-state-result.png|thumb|400px|none|]] | ||

| + | |||

==== Coherent states ==== | ==== Coherent states ==== | ||

| + | |||

Now consider the challenge of creating a coherent state | Now consider the challenge of creating a coherent state | ||

:<math> | :<math> | ||

| Line 269: | Line 264: | ||

ion, two Raman beams can be applied to effect such a Hamiltonian: | ion, two Raman beams can be applied to effect such a Hamiltonian: | ||

::[[Image:Quantum_control_and_trapped_ions-qcontrol-cstate.png|thumb|400px|none|]] | ::[[Image:Quantum_control_and_trapped_ions-qcontrol-cstate.png|thumb|400px|none|]] | ||

| − | + | ||

The two beams are detuned from the upper <math>P</math> state to a virtual level | The two beams are detuned from the upper <math>P</math> state to a virtual level | ||

<math>P'</math>, and have a frequency difference of <math>\nu</math>, the vibrational | <math>P'</math>, and have a frequency difference of <math>\nu</math>, the vibrational | ||

| Line 281: | Line 276: | ||

adiabatically eliminated following the standard treatment for Raman | adiabatically eliminated following the standard treatment for Raman | ||

transitions. | transitions. | ||

| + | |||

This interaction can also be physically pictured as arising from the | This interaction can also be physically pictured as arising from the | ||

"moving standing wave" created by the two counter-propagating Raman | "moving standing wave" created by the two counter-propagating Raman | ||

beams: | beams: | ||

::[[Image:Quantum_control_and_trapped_ions-qcontrol-raman.png|thumb|400px|none|]] | ::[[Image:Quantum_control_and_trapped_ions-qcontrol-raman.png|thumb|400px|none|]] | ||

| − | + | ||

This results in a field intensity <math> \langle (\vec{E}_1 + \vec{E}_2)^2 \rangle \sim | This results in a field intensity <math> \langle (\vec{E}_1 + \vec{E}_2)^2 \rangle \sim | ||

\cos(\Delta k z + \Delta \omega t)</math>, causing an AC stark shift of | \cos(\Delta k z + \Delta \omega t)</math>, causing an AC stark shift of | ||

| Line 306: | Line 302: | ||

the expected <math>P_g</math> as function of the probing sideband pulse width: | the expected <math>P_g</math> as function of the probing sideband pulse width: | ||

::[[Image:Quantum_control_and_trapped_ions-fig4-coherent-state-result.png|thumb|400px|none|]] | ::[[Image:Quantum_control_and_trapped_ions-fig4-coherent-state-result.png|thumb|400px|none|]] | ||

| − | ==== Schr | + | |

| + | ==== Schrödinger cat state ==== | ||

| + | |||

The superposition of two coherent states, <math>|\alpha \rangle + |-\alpha{\rangle}</math>, | The superposition of two coherent states, <math>|\alpha \rangle + |-\alpha{\rangle}</math>, | ||

| − | has been likened to being a Schr | + | has been likened to being a Schrödinger cat state; for an atom in |

this motional state of oscillation, it implies the atom is superposed | this motional state of oscillation, it implies the atom is superposed | ||

in two positions simultaneously. Creating such a cat state can be | in two positions simultaneously. Creating such a cat state can be | ||

| Line 346: | Line 344: | ||

<math>z_0\sim 7</math> nm, and the ion size <math>a_0\sim 0.1</math> nm: | <math>z_0\sim 7</math> nm, and the ion size <math>a_0\sim 0.1</math> nm: | ||

::[[Image:Quantum_control_and_trapped_ions-fig6-cat-state-result.png|thumb|400px|none|]] | ::[[Image:Quantum_control_and_trapped_ions-fig6-cat-state-result.png|thumb|400px|none|]] | ||

| + | |||

=== Arbitrary motional states === | === Arbitrary motional states === | ||

| + | |||

Quantum control allows arbitrary motional states of an ion to be | Quantum control allows arbitrary motional states of an ion to be | ||

systematically constructed using the carrier and sideband control | systematically constructed using the carrier and sideband control | ||

| Line 363: | Line 363: | ||

ladder picture of energy eigenstates: | ladder picture of energy eigenstates: | ||

::[[Image:Quantum_control_and_trapped_ions-qcontrol-arbmot.png|thumb|400px|none|]] | ::[[Image:Quantum_control_and_trapped_ions-qcontrol-arbmot.png|thumb|400px|none|]] | ||

| − | + | ||

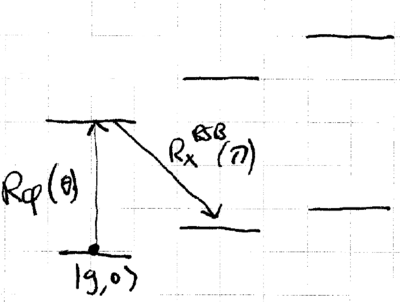

Starting from <math>|g,0{\rangle}</math>, a carrier transition pulse <math>R_\phi(\theta)</math> is | Starting from <math>|g,0{\rangle}</math>, a carrier transition pulse <math>R_\phi(\theta)</math> is | ||

used to move a desired amplitude to <math>|e,0{\rangle}</math>, then a red sideband | used to move a desired amplitude to <math>|e,0{\rangle}</math>, then a red sideband | ||

<math>\pi</math> pulse <math>R_x^{RSB}(\pi)</math> moves this to <math>|g,1{\rangle}</math>. Appropriately | <math>\pi</math> pulse <math>R_x^{RSB}(\pi)</math> moves this to <math>|g,1{\rangle}</math>. Appropriately | ||

iterating on this sequence allows creation of an arbitrary motional state. | iterating on this sequence allows creation of an arbitrary motional state. | ||

| + | |||

This should come as no surprise, since we have already noted that the | This should come as no surprise, since we have already noted that the | ||

system is controllable. Of course, as we have seen, special states | system is controllable. Of course, as we have seen, special states | ||

| Line 376: | Line 377: | ||

realizations of quantum control schemes, is thus an interesting | realizations of quantum control schemes, is thus an interesting | ||

challenge and an experimental art. | challenge and an experimental art. | ||

| + | |||

| + | === References === | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:Ion traps and quantum information]] | ||

| + | [[Category:QCQI]] | ||

Latest revision as of 00:22, 9 June 2009

Laser cooling is a process which allows atoms to be brought to their motional ground state, or into a condensate state. A natural generalization would be to devise processes which allow atoms to be brought to arbitrary quantum states; this is a goal of a growing subject area known as quantum control. In this section, we consider an example of open loop quantum control, as an illustrative example of this area of inquiry, focused on creation of arbitrary states of motion of a single ion.

Contents

Quantum control in perspective

Quantum control has many applications in modern physics. Chemical reaction rates can be highly dependent on the electronic, magnetic, and motional states, of the reactants; it has been shown that femptosecond laser excitation can be used to enhance and steer reactions by controlling these quantum states. Biological molecules involve energy transfer, for example, in photosynthesis, which couple electron transfer and conformation changes on short timescales; it has been shown that these processes have important coherent steps which can also be externally controlled and shaped. And atomic physics makes increasing use of exotic quantum states, including squeezed states and entanglement, for precision metrology and studies of fundamental quantum physics.

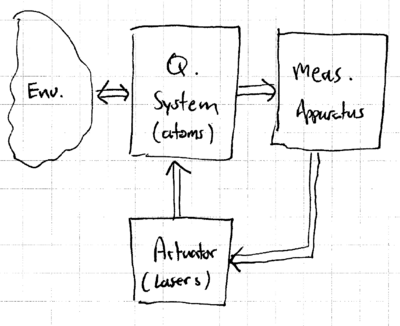

The concept of quantum control builds on the extensive field of classical control of dynamical systems. Classical control theory provides basic definitions for the model system, what it means to be able to control the system ("control objectives"), general strategies for achieving control and evaluating things such as the robustness of the control, and theorems with conditions which must be satisfied for a system to be controllable. We may model a quantum system being controlled as having, in addition to the quantum system itself (eg atoms) and its environment, a measurement apparatus (eg fluorescence detectors), and an actuator acting back on the system (eg lasers):

Two main control objectives, in this context, are (1) state engineering: steering the quantum system into an arbitrary quantum state, and (2) process engineering: realizing an arbitrary unitary transform on the quantum system.

Many general strategies exist for achieving these quantum control objectives. Broadly, these all involve some modification of the system Hamiltonian using control Hamiltonian . Strategies include:

- Open loop control: no feedback, state is known

- Closed loop control: feedback based on classical measurement record, with either weak measurements and continuous

feedback, or strong measurement and feedback at discrete times, or adaptive measurements changed based on classical record

- Coherent control: use of an ancilla quantum system in place of the measurement and actuator, with controllable coupling to the system under control

- Learning control: applied to ensembles, with feedforward control in place of feedback to systems individually

The presence of interactions with an environment significantly complicates quantum control. Also, in strong contrast to classical control, measurement of a quantum system produces significant back-action, and if not applied appropriately, can collapse desired superposition states. Noisy actuation also induces quantum noise in the system, which must be dealt with using unusual methods, such as quantum error correction and decoherence free subsystems, if fragile entanglement is to be preserved. Many conceptual issues remain to be resolved in defining scenarios for application of quantum control. However, at least for the simplest scenarios, useful and clear limits can be established. And in the absence of decoherence, if a system is not controllable, then it is likely that the presence of decoherence will not improve controllability. For example, one basic theorem in quantum control is the following:

Theorem: A (closed) quantum system with Hamiltonian , in Hilbert space , with controls , is {\em controllable} iff any Hamiltonian on can be generated in the closure of .

In this theorem, closure refers to the completion of the algebra of the Hamiltonians by commuting all given Hamiltonians with each other, recursively, until no new terms are produced. If any Hamiltonian on can be expressed as a linear combination of these terms, then the system is controllable. Some examples are helpful in illustrating this theorem.

- Example 1: , . This system is controllable, because any can be generated by and , since .

- Example 2: , . This system is not controllable.

- Example 3: , . This system is not controllable.

- Example 4: , . This system is not controllable.

- Example 5: , ( and are the control parameters). This system {\em is} controllable.

The last of these examples describes a single trapped ion, controlled by incident laser light, as we shall now explore.

Motional state control: a trapped ion

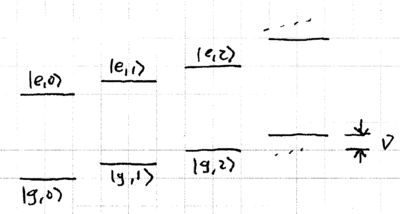

Let us consider quantum control of a single trapped ion, modeled by a system of photon + atom + phonon. We will let the photon light field be classical, and treat the atom and phonon quantum-mechanically. The energy eigenstates of the atom + phonon system may be depicted as a ladder:

And as we have previously seen, the interaction Hamiltonian is

The motion-changing amplitudes of this interaction we are interested in come from

which are, to lowest order in the Lamb-Dicke parameter ,

These three correspond to the carrier transition and the blue and red sidebands:

When the laser is near resonance, , such that the detuning , and the incident intensity is low, such that , the effective Hamiltonian of the system is

Physically, this describes the interaction of a well-localized ion, having momentum spread greater than the recoil momentum from a single photon. Absorption of a photon in this case cannot excite phonons; just as in the M\"ossbauer effect, the phonon spectrum has a gap in the energy spectrum at the recoil energy, causing the whole atom and trap to recoil instead of just the atom.

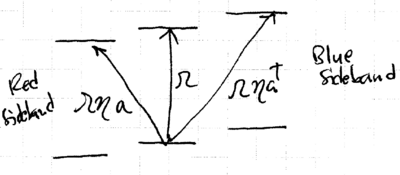

When the laser is detuned to , the red sideband is excited, giving the approximate Hamiltonian

This is identical to the Cavity-QED in the strong coupling limit, described by the Jaynes-Cummings Hamiltonian. The light couples states on the ladder with Rabi frequencies which grow as :

When the laser is detuned to , the blue sideband is excited, giving the approximate Hamiltonian

This is known as the "anti Jaynes-Cummings" Hamiltonian, with light coupling states on the ladder as:

Given that pairs of levels are coupled independently by the sideband excitation, it is convenient to define Rabi frequencies for these pairs, .

Fock, coherent, and Schrödinger cat states of an ion

Let us now turn to the challenge of creating specific motional states of a trapped ion, using the given carrier and sideband Hamiltonians. First, note that the state can be prepared using Doppler cooling, followed by resolved sideband cooling.

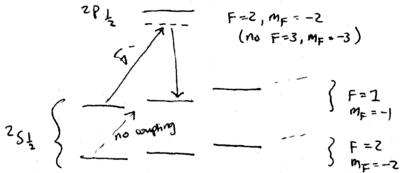

What experimental signature attests to the ion being in the state? One ion used in experiments is Ba, which has three relevant levels, much like most ions trapped:

Because of the extraordinary second lifetime of the state, fluorescence jumps are observed in the nm spectrum, as the ion is weakly excited at nm:

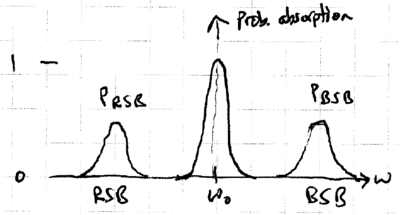

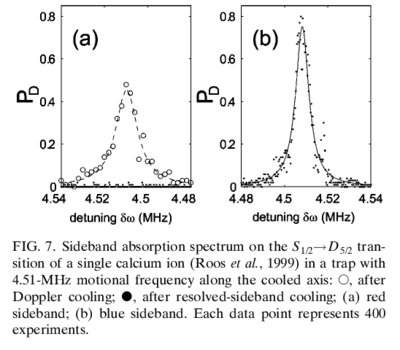

(this and other data shown here taken from {\em Quantum dynamics of single trapped ions}, by Leibfried, Blatt, Monroe, and Wineland, Rev. Mod. Phys., v75, p281, 2003). The statistics of such jumps provides very sensitive information about the internal state of an ion. Specifically, as the narrow S-D frequency laser is scanned through the sideband frequencies, a spectrum such as this is observed:

Let and be the intensities of the observed red and blue sidebands, respectively. When the motional quantum number has a thermal distribution, it is straightforward to show that the ratio of these two intensities gives

such that the mean phonon number is

This is a sideband spectrum been obtained after resolved sideband cooling:

Fock states

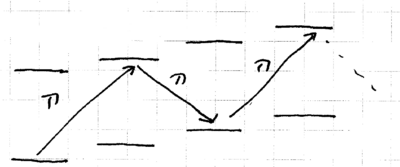

Now consider the challenge of creating not just , but rather a nonzero Fock state of the ion motion, . This can be realized, in principle, by applying a sequence of pulses on the blue sideband:

The unitary transformation effected by laser on the blue sideband perform rotations on the two-level manifolds which the excitations connect, described by

and similarly for the red sideband, so that

where an approximation comes from assuming that the Rabi frequencies for all the transitions are the same. They are not: they increase as , so the pulse widths (or intensities) must increase as increases. Odd numbered Fock states can be created by inserting an additional carrier pulse.

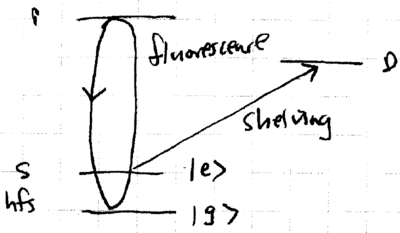

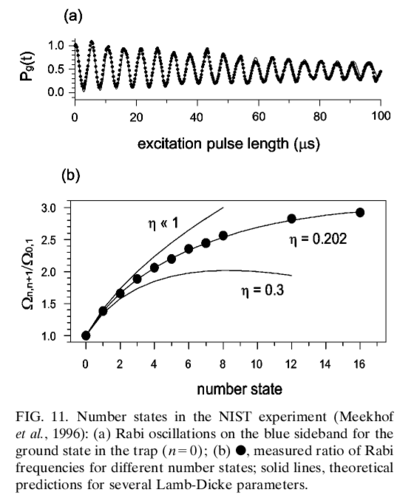

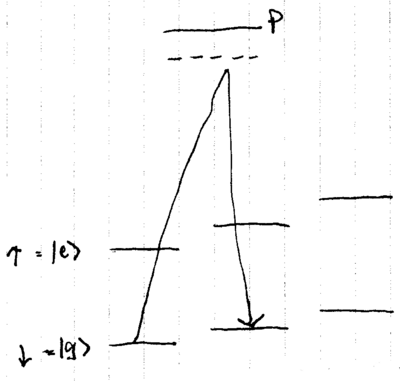

Experimentally, the signature of having created can be obtained by measuring the Rabi frequency of the sideband, since . This can be measured in many ions by using hyperfine states to represent and , and measuring the probability of being in after a blue sideband pulse of varying time . An important experimental technique involved is temporarily mapping to a non-fluorescing state such as the D level, such that the ion will fluoresce strongly only if it is in . This is known as shelving:

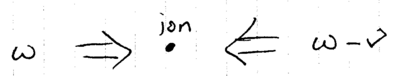

Shelving allows measurement of with fidelity better than is many ions, such as Be, in a time as short as s, with good photomultipliers and reasonable fluorescence collection efficiency. Using this technique, creation of states has been verified experimentally:

Coherent states

Now consider the challenge of creating a coherent state

This is a "classical" state, so intuitively, it is reasonable to think there should be a way to generate this state without going to a great deal of trouble, or much fine control. Indeed, it helps to recall that the coherent state is a displaced vacuum state,

where the displacement operator represents a classical force applied at the frequency of the oscillator, described by Hamiltonian . For the case of a trapped ion, two Raman beams can be applied to effect such a Hamiltonian:

The two beams are detuned from the upper state to a virtual level , and have a frequency difference of , the vibrational frequency of the trapped ion. The Hamiltonian realized is

where the approximation becomes valid when the virtual level is adiabatically eliminated following the standard treatment for Raman transitions.

This interaction can also be physically pictured as arising from the "moving standing wave" created by the two counter-propagating Raman beams:

This results in a field intensity , causing an AC stark shift of of

The dipole force experienced by an atom in this potential is

which oscillates at the vibrational frequency, since . This picture thus confirms that the Raman beams drive the motional mode of the ion, and a coherent phonon state is thus produced from the driven harmonic motion. Experimentally, confirmation of the creation of such a coherent state has been obtained, by agreement with the expected as function of the probing sideband pulse width:

Schrödinger cat state

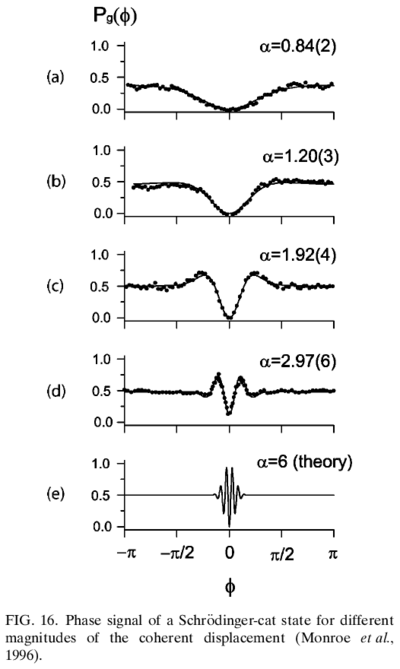

The superposition of two coherent states, , has been likened to being a Schrödinger cat state; for an atom in this motional state of oscillation, it implies the atom is superposed in two positions simultaneously. Creating such a cat state can be accomplished with a trapped ion by applying a refined version of the Raman excitation used in creating a coherent state. Instead of exciting both spin states, polarized light can be applied to selectively apply the force only when the ion is in the state (example given for levels in Be:

This state-dependent force is then applied in the following procedure:

Afterwards, the probability of finding the ion in the ground state is

Experimentally, this probability dependence on has been confirmed, for various values of , up to , corresponding to an ion separation of nm, which is much larger than the vibrational wavefunction ground-state spread nm, and the ion size nm:

Arbitrary motional states

Quantum control allows arbitrary motional states of an ion to be systematically constructed using the carrier and sideband control Hamiltonians. Suppose we desire the state

Then there exist and such that

The validity of this recipe is straightforward to understand from the ladder picture of energy eigenstates:

Starting from , a carrier transition pulse is used to move a desired amplitude to , then a red sideband pulse moves this to . Appropriately iterating on this sequence allows creation of an arbitrary motional state.

This should come as no surprise, since we have already noted that the system is controllable. Of course, as we have seen, special states such as the coherent state can be realized more directly, and such direct recipes are often more robust against control errors, and can be quick enough to avoid decoherence induced, for example, by spontaneous emission. The physics of quantum control, and practical realizations of quantum control schemes, is thus an interesting challenge and an experimental art.

![{\displaystyle [\sigma _{x},\sigma _{z}]=-2i\sigma _{y}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/bafd3b1ceb94242fdad1ed98c3c8cd80a2645e93)

![{\displaystyle H_{ctrl}=\Omega (t)\cos[\eta (a+a^{\dagger })-\omega t]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/1560ab414fbfc1d9cb6e71bfce36c9f0f47ddef8)

![{\displaystyle H_{I}=\Omega \cos \left[{\eta (a+a^{\dagger })-\omega t}\right]\,.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/6f7d7b722fe9f2f5b9a4fa841a6a91d598cfaf13)

![{\displaystyle R_{\phi }^{BSB}(\theta )=\exp \left[{i{\frac {\theta }{2}}(e^{i\phi }\sigma ^{+}a+e^{-i\phi }\sigma ^{-}a^{\dagger })}\right]\,,}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/cad2d58955f443be484424e5b707c5affc8d9259)

![{\displaystyle |g,2n\rangle \approx \left[{R_{x}^{RSB}(\pi )R_{x}^{BSB}(\pi )}\right]^{n}|g,0{\rangle }\,,}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/100f02cffc6d4c5c3e3fd743e24ef74460521925)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{array}{rcl}{\rm {start}}&\rightarrow &{\rm {Prepare}}~|g,0{\rangle }\\R_{y}(\pi /2)&\rightarrow &|g,0\rangle +|e,0{\rangle }\\D(\alpha )~{\rm {if}}~|e\rangle &\rightarrow &|g,0\rangle +|e,\alpha {\rangle }\\R_{x}(\pi )&\rightarrow &|e,0\rangle +|g,\alpha {\rangle }\\D(e^{i\phi }\alpha )~{\rm {if}}~|e\rangle &\rightarrow &|e,e^{i\phi }\alpha \rangle +|g,\alpha {\rangle }\\R_{y}(\pi /2)&\rightarrow &|g\rangle \left[{|e^{i\phi }\alpha {\rangle }+|\alpha \rangle }\right]+|e\rangle \left[{|e^{i\phi }\alpha {\rangle }-|\alpha \rangle }\right]\,.\end{array}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/2db4c5ba80e5c71015b00c388d408b217cc57493)

![{\displaystyle P_{g}={\frac {1+|{\langle }\alpha |e^{i\phi }\alpha {\rangle }|^{2}}{2}}={\frac {1}{2}}\left[{1+e^{-\alpha ^{2}(1-\cos \phi )}\cos(\alpha ^{2}\sin \phi )}\right]\,.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/acf4e6f443a1f34b3ecd65509e1618530de5b6c5)

![{\displaystyle |\psi \rangle =\prod _{n=0}^{N}\left[{R_{x}^{RSB}(\pi )R_{\phi _{n}}(\theta _{n})}\right]|g,0{\rangle }\,.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/0e4e580ee8d8ff63b30af41a3b34f14925d3c5ed)