Difference between revisions of "Coherence"

imported>Q liang |

imported>Q liang |

||

| Line 525: | Line 525: | ||

<math><S,M-1|S_-|S,M>=\sqrt{(S-M+1)(S+M)}</math> | <math><S,M-1|S_-|S,M>=\sqrt{(S-M+1)(S+M)}</math> | ||

| − | Note matrix element only couple within one ladder. For single particle, <math>S=M=\frac{1}{2}\Rightarrow<S,M-1|S_-|S,M>=1</math> | + | Note matrix element only couple within one ladder. For single particle, <math>S=M=\frac{1}{2}\Rightarrow<S,M-1|S_-|S,M>=1</math>. |

| − | Rate (or intensity I) of radiation relative to a single particle | + | Rate (or intensity I) of radiation relative to a single particle:<math>I=(S-M+1)(S+M)</math> |

| − | |||

| − | <math>I=(S-M+1)(S+M)</math> | ||

Let's look at <math>S=\frac{N}{2}</math> | Let's look at <math>S=\frac{N}{2}</math> | ||

Revision as of 14:37, 15 July 2012

We speak of coherence if there exist well defined phases between two or more amplitudes that can interfere. These can be, e.g., the relative phase of the electric field in two arms of an interferometer, the relative phase of two or more states within one atom, or the relative phase of oscillating dipole moments in different atoms. Coherence is often a measurement tool in that the relative phase is the time integral over the energy difference between the states. For instance, if the atomic states have different magnetic moments, coherence between them provides a very sensitive measurement tool for magnetic field, or if the states have different spatial wavefunctions, the relative phase is a sensitive measure of the gravitational energy difference. In atomic clocks, coherence allows one to transform as energy difference between two internal atomic states into a frequency and time standard.

Contents

- 1 Coherence in two-level systems

- 2 Precession of a spin in a magnetic field

- 3 The Stern-Gerlach experiment and spatial loss of coherence

- 4 Quantum Beats

- 5 Clarification on coherence and dipole moment

- 6 First observation of coherent population trapping CPT

- 7 Absorption calculation by interference, gain without inversion

- 8 Electromagnetically induced transparency

- 9 EIT: Eigenstates picture

- 10 STIRAP in a three-level system

- 11 Example: Five-level non-local STIRAP

- 12 On the "magic" of dark-state adiabatic transfer

- 13 Two-phase absorption, Fano profiles

- 14 Slow light, adiabatic changes of velocity of light

- 15 Superradiance

- 16 Superradiance, continued

- 17 Supperradiance in N atoms

- 18 Dicke states of extended samples

- 19 Oscillating and overdamped regimes of superradiance

- 20 Raman Superradiance

- 21 Storing light, catching photons

- 22 Notes

Coherence in two-level systems

A two-level atom that has been prepared by a pulse in a superposition can be viewed as exhibiting coherence, since the phase between and is well defined, and the system will evolve coherently as for times , where is the decay rate constant for the excited state. Figure \ref{fig:single-atom-coherence} displays a conceptual experiment that can be used to test this. \begin{figure} \centering

\caption{Measurement of definite phase for light emitted by a two-level atom prepared with a pulse. The laser light is sent through both arms of an interferometer; a switch in one arm selects a pulse of light from the laser with which to excite the atom. The light the atomic dipole emits is then mixed with the other interferometer arm at the output. Averaging the output signal over many repetitions of the experiment, the interferometer measures a definite phase for the light emitted by the atom, defined relative to the phase of the exciting pulse.}

\end{figure} What about an atom prepared by a pulse in ? There is no coherence at , since the atom is in a single state, but what about ? Then the atom is in a superposition of states . Obviously some phase must exist, because otherwise no dipole moment exists that can emit (), but the phase is completely unpredictable, so the experiment pictured above (or an emsemble average, as in Figure \ref{fig:ensemble-average-coherence}) would yield no definite phase. We conclude that an atom prepared in does not exhibit coherence. \begin{figure} \centering

\caption{Ensemble average of the phase measurement.}

\end{figure} The ensemble average (parallel setups) or time average (repeated experiment at same location) yields no definite phase, so we conclude that the expectation value of the dipole moment is zero at all times. What is the origin of uncertain phase ? Vacuum fluctuations. What then happens if we place two atoms close together and excite them at the same time? Is the relative phase of the evolving dipole moments fixed or uncertain? If the relative phase is fixed, how close must the atoms be for the relative phase to be well defined? These questions about spatial coherence and Dicke superradiance will be covered later in the chapter.

Precession of a spin in a magnetic field

Precession of a spin can be viewed as an effect of coherence since . In a magnetic field , so the precession is due to a coherence between the components of the spin. If no coherence existed, the spin would be in a statistical mixture of and . In the density matrix formalism,

in the z basis .\\The expectation value of ,

If the coherences (off-diagonal elements of ) were smaller, would be smaller. For a statistical mixture of and , and .

The Stern-Gerlach experiment and spatial loss of coherence

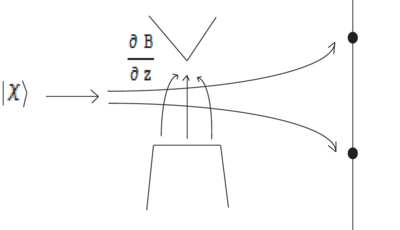

\begin{figure} \centering

\caption{Stern-Gerlach experiment. Where in the magnet (or outside) does the projection onto occur?} \end{figure} In the Stern-Gerlach experiment a particle initially spin-polarized along has equal probability of following either the trajectory or the trajectory. So initially the particle is described by a density matrix for a pure state,

after passing the Stern-Gerlach apparatus (inhomogeneous magnetic field) the density matrix is

with no intereference possible between the two states. Why? Because describing the full quantum state of the particle also requires acocunting for its spatial wavefunction. The density matrix above does not contain all the relevant degrees of freedom. Correctly, the particle should initially be described by

with , i.e. a spatial wavefunction independent of internal state, . In the inhomogeneous magnetic field, the wavefuntion components evolve differently because there is a different potential energy seen by the two spin states :

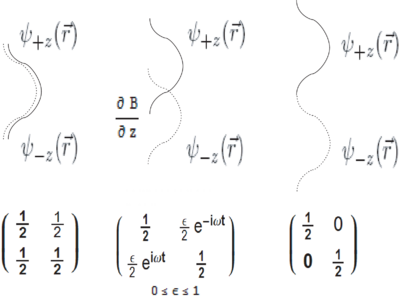

\begin{figure} \centering

\caption{Spatial wave function and corresponding spin density matrix in the Stern-Gerlach experiment.} \end{figure} The coherence (interference) between and components to form exists only in the region where there is at least partial overlap between the two wavefunctions . When the wavefunctions do not overlap, there is no significance to a relative phase between and , i.e. no interference term. (Of course, if the wavefunctions are steered back to overlap, we can ask if there was a well-defined relative phase between them while they were separated.) In a more complete description, the inhomogeneous magnetic field entangles the spatial and spin degrees of freedom. When the spatial overlap disappears, or equivalently, when we trace over the spatial wavefunction (by measuring the particle either at location 1 or at location 2), the interference between and giving rise to disappears. In a measurement language, the inhomogeneous magnetic field entangles the "variable" () with the "meter" (the spatial wavefunctions of the particle). Once the spatial wavefunctions cease to overlap, the particle's position can serve as a "meter" for the variable to be measured, the spin along . However, until the particle hits the screen, or is subjected to uncontrolled or unknown magnetic fields, the meter-variable entanglement is still reversible, and a "measurement" has not been made.

Quantum Beats

Quantum beats can be thought of as a two-level effect, though they are observed in multilevel atoms. They allow one to measure level spacings with high resolution when a narrowband excitation source (narrowband laser) is not available. \begin{figure} \centering

\caption{Multiple levels within energy from ground state, ,\ldots}

\end{figure} Consider the scenario of Figure \ref{fig:qb-levels}, where we have multiple excited levels in a narrow energy interval , all decaying to a common ground state. If we excite with a pulse of duration , we cannot resolve the levels, and they will be populated according to the coupling strength to the ground state for the given excitation method:

and for times , the state vector is

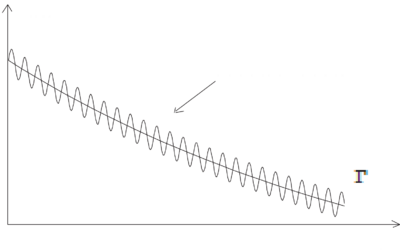

It follows that, in directions where the radiation from the levels interferes, there will be oscillating terms at frequencies on top of the excited state decay. \begin{figure} \centering

\caption{Quantum beats}

\end{figure} This allows one to measure excited-state splittings in spite of the lack of a sufficiently narrow excitation source. Compared to our initial example of a two-level atom, here the coherence is initially purely between the excited states (definite excitation phase between them), and no coherence between and exists initially. Of course, as the atom decays, coherence between and (e.g. dipole moments) build up, and the coherence between the emitted fields of the different dipoles gives rise to the observed effect. Figures \ref{fig:qb-ideal} and \ref{fig:qb-data} show respectively an idealized quantum beat signal and real data from an experimental demonstration of the technique. \begin{figure} \centering

\caption{Schematic level diagrams and observed quantum beats of at 475 keV/atom; H, n=3, and H, n=4 at 133 keV/atom. \cite{Andra1970}}

Clarification on coherence and dipole moment

Consider the coherence of the atom after coherent excitation with a short pulse (shorter than emission rate). Let the state of the atom be . Then, the coherence between and is maximum for , i.e. with pulse. (Coherence is in the density matrix. For a pure state, it is ). Now, let us consider a system with the atom and (external) EM mode. We consider the case where there is only a single EM mode coupled to the atom (ex, an atom strongly coupled to a cavity). Then, emission couples atomic states with photon number states: and . Thus, a pulse also maximizes the coherence and .

On the other hand, for continuous excitation (not a short pulse), saturation of the atom leads to emission of increasingly incoherent light (Mollow triplet). For Mollow triplet, see Cohen-Tannoudji p:424.

Next, consider a coherent light which is very weak. Monochromatic, coherent light is represented by a coherent state that has a Poissonian distribution of photon numbers: . For , the population of the states with is negligible, and the atom prepared in a state with emits a coherent state of light, in agreement with what is expected for small saturation.

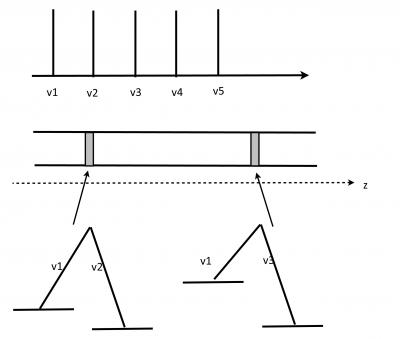

First observation of coherent population trapping CPT

Prepare a multimode laser with regular frequency spacing (, in the figure).

Prepare a gas in a cylindrical volume with gradient of magnetic field in z direction, and observe fluorescence.

Dark regions show the phaces where Zeeman shift between magnetic sublevels equals frequency difference between laser modes.

Absorption calculation by interference, gain without inversion

(Steve Harris, PRL 62, 1033 (1989)) http://prl.aps.org/abstract/PRL/v62/i9/p1033_1

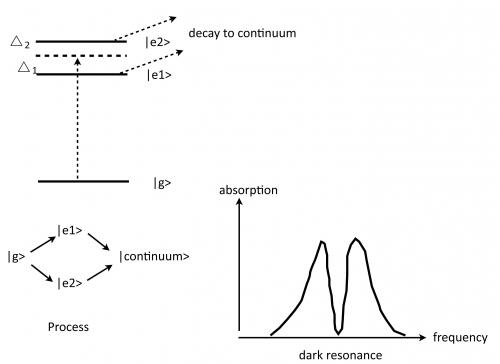

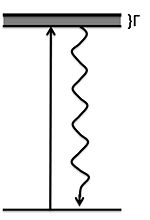

It is commonly believed that we need for optical gain. But: Consider a V system with two unstable states that decay by coupling to the same continuum (This is a fairly special situation, e.g. different m-levels do not qualify, since they emit photons of different polarizations, thus the continue or are distinguishable.)

Consider three level systems as in the figure where and decay to the continuum. A surprising feature of this system is the fact that there is a frequency at which the absorption rate becomes zero. To formally confirm this, we need to compute the second-order matrix element . Then, we know that there is a frequency at which this matrix element almost cancels. Let the frequency be that corresponds to an energy between the two levels. Note depends on the two matrix elements and we assume .

One may understand this by considering the fact that the two-photon scattering process can proceed via two pathways that are fundamentally indistinguishable. In other words, it is impossible to tell whether it came from or . Thus, we need to consider quantum interference between them.

Now assume that with some mechanism we populate, say, with a small number of atoms . These atoms have maximum stimulated emission probability on resonance, , but there is also even larger absorption, since . However, because of the finite linewidth of level , there is also stimulated emission gain at the "magical" (absorption-free) frequency . Since the atoms do not absorb here, there is net gain at this frequency in spite of , which can lead to "lasing without inversion." Note: this only works if the two excited states decay to the same continuum, such that the paths are indistinguishable. How can a system for lasing without inversion be realized?

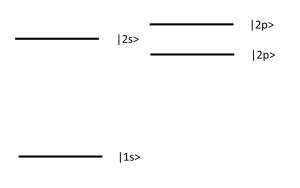

Possibility 1: hydrogen and dc electric field

Possibility 2: use ac electric field to mix non-degenerate s state with p state.

Electromagnetically induced transparency

"Is it possible to send a laser beam through a brick wall?"

Radio Yerevan: "In principle yes, but you need another very powerful laser..."

Steve Harris thought initially of special, ionizing excited states. However it is possible to realize the requirement of identical decay paths in a -system with a a(strong) coupling laser. The phenomenon is closely related to coherent population trapping.

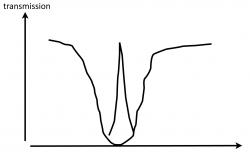

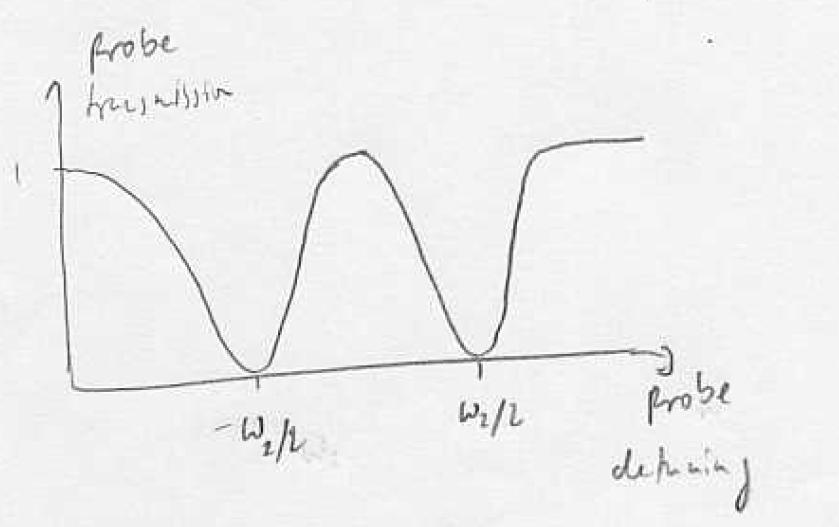

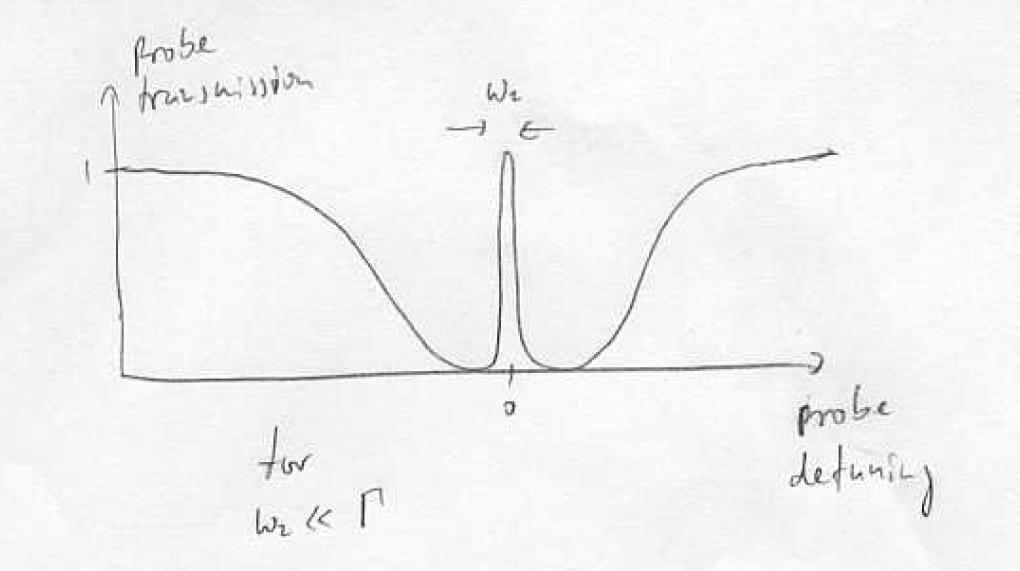

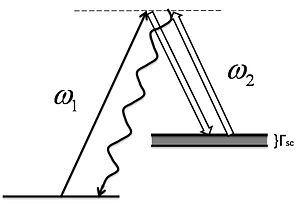

For resonant fields , we have

As we turn up the power of the coupling laser the transmission improves and then broadens (in the realistic case of a finite decoherence rate , an infinitesimally small coupling Rabi frequency, but the frequency window over which transmission occurs is very narrow and given by .

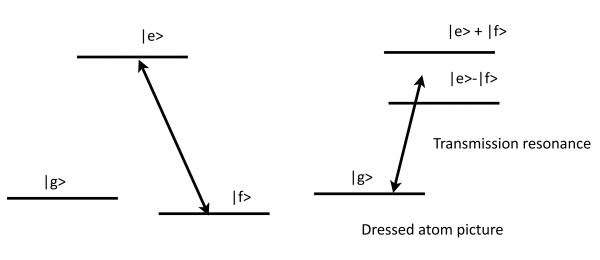

EIT: Eigenstates picture

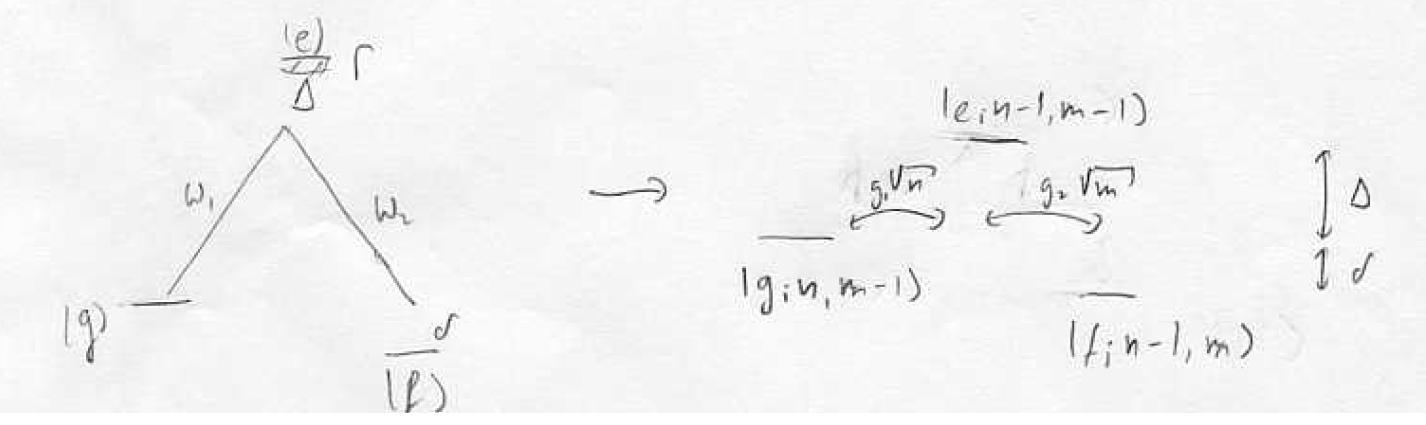

Using the field quantization to easily include energy conservation, we see that the states are coupled in triplets:

So the Hamiltonian is given by

On resonance the Eigenstates are

In the limit of weak probe and a strong pump,

we can limit the analysis to . Then we can diagonalize the strong coupling, and treat the probe perturbatively

Again we have a scattering problem

via a two photon process. The matrix element contains two intermediate states with opposite detunings.

On one- and two-photon resonance all couplings are symmetric in and , the detunings are opposite, and the matrix element M vanishes: electromagnetically induced transparency (EIT). If the pump remains on resonance and we tune the probe field, then the couplings are still symmetric in , , but the detunings are , and the matrix element does not vanish. Maximum scattering is obtained when we tune to one of the bright states

When we include the decay within the system, we can no longer use the Hamiltonian formalism, but must use density matrices. Nevertheless, the eigenstates provide physical insight into the problem.

STIRAP in a three-level system

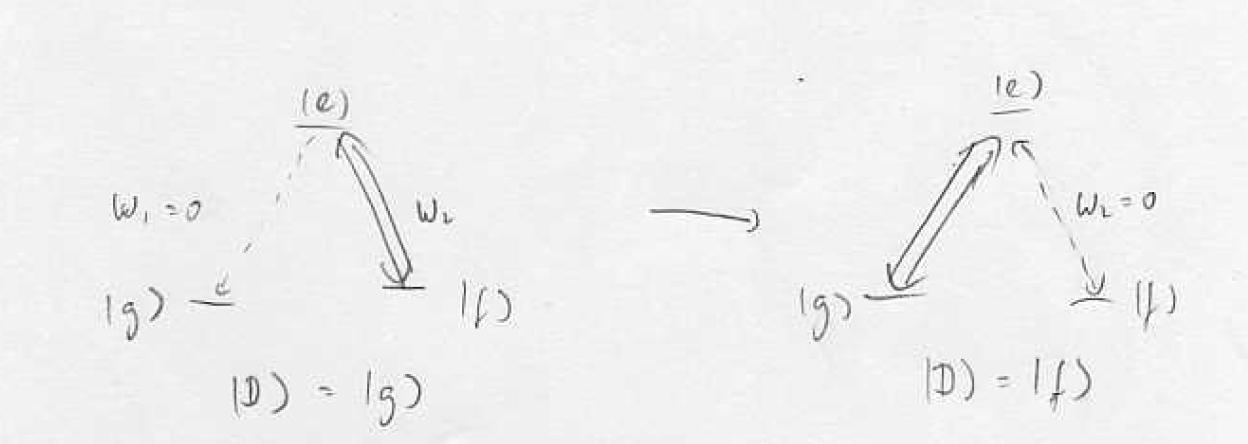

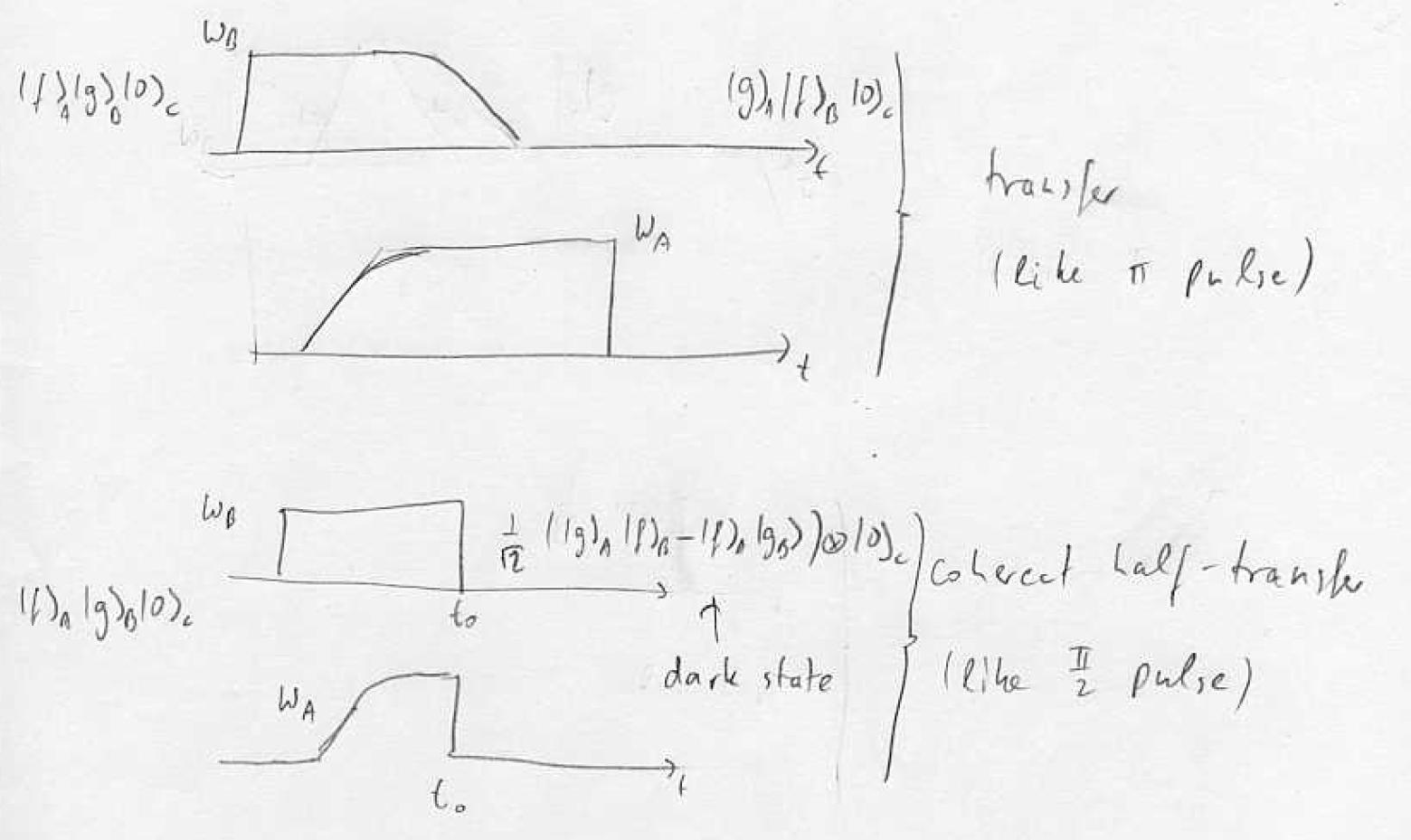

If at least one of the two coupling beams is non-zero, there is always a finite energy spacing between the dark state and the bright states. This allows one, by changing the ration of the coupling beams, to adiabatically change the character of the dark state between |g> and |f> while not populating the bright states (and thus the excited state). By use of the so-called "counterintuitive pulse sequence"

STIRAP of this type in a three-level system is also called "dark-state transfer."

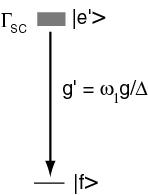

Example: Five-level non-local STIRAP

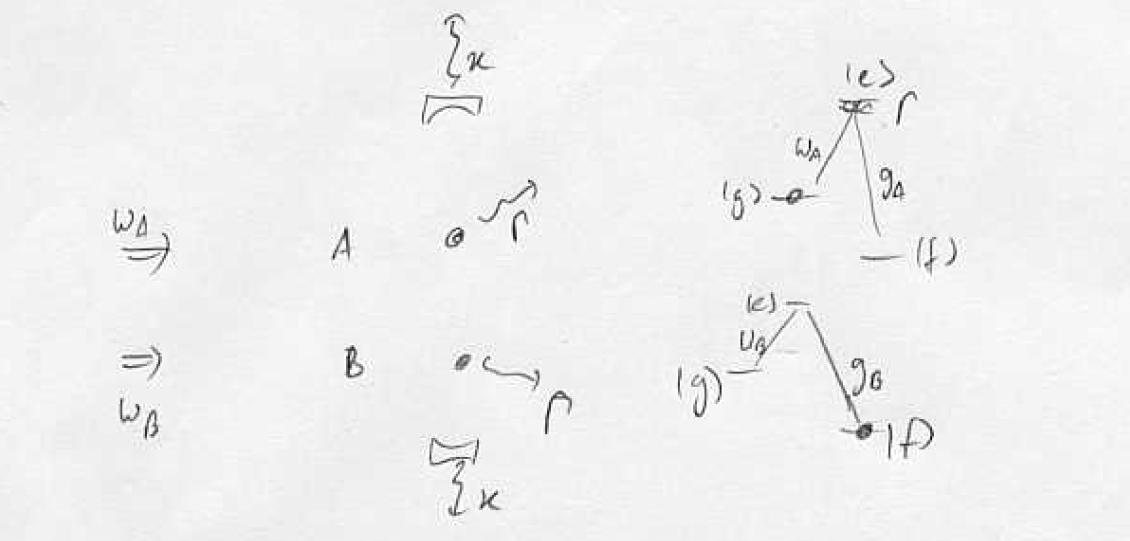

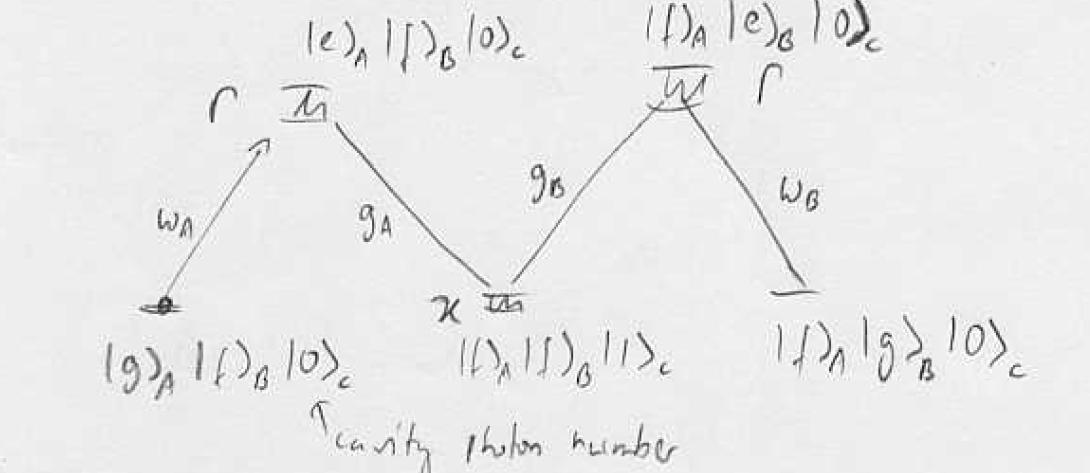

Atom A contains hyperfine excitation, can we transfer the hyperfine excitation from A to B without losing it from the cavity? Cavity strongly coupled to A,B with single-photon Rabi frequency g. Dark-state adiabatic transfer with virtual excitation of the cavity mode is possible:

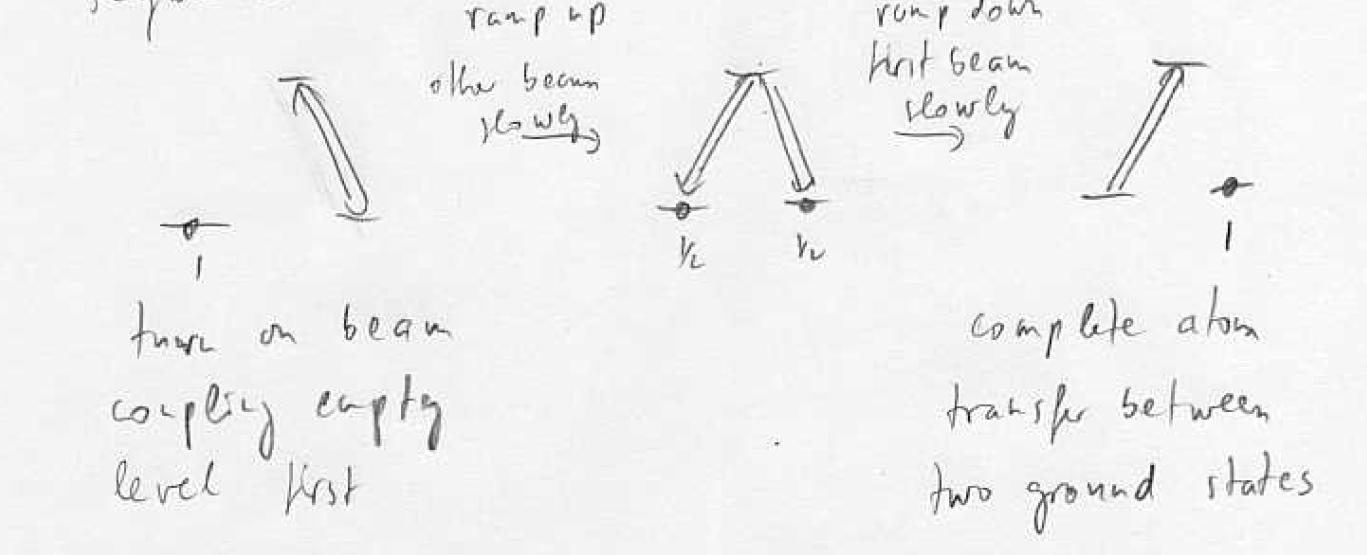

Procedure: turn on first coupling empty level, ramp up , ramp down adiabatic transfer via dark state of the cavity. Note that the probability to find the photon in the cavity can be made very small while maintaining full transfer: virtual states.

If we stop the transfer suddenly half-way we create an entangled state where the single hyperfine excitation is shared between the two samples.

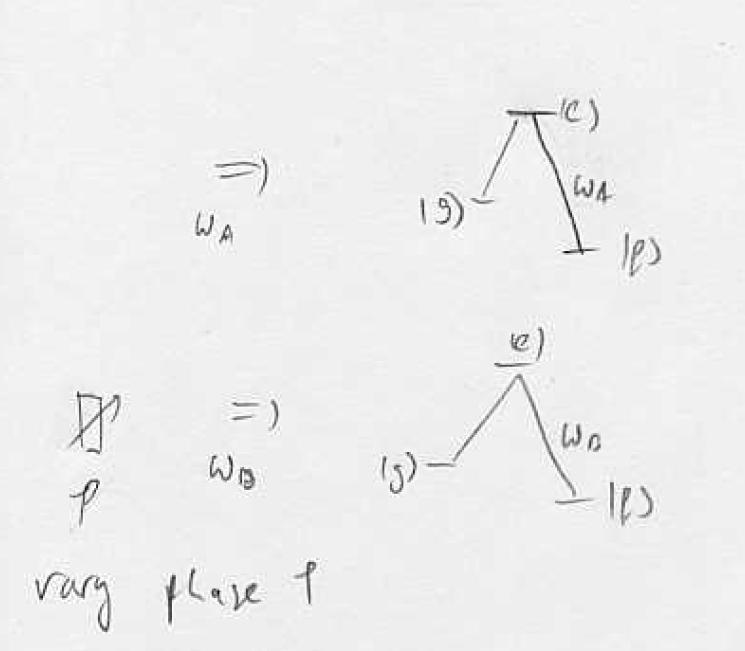

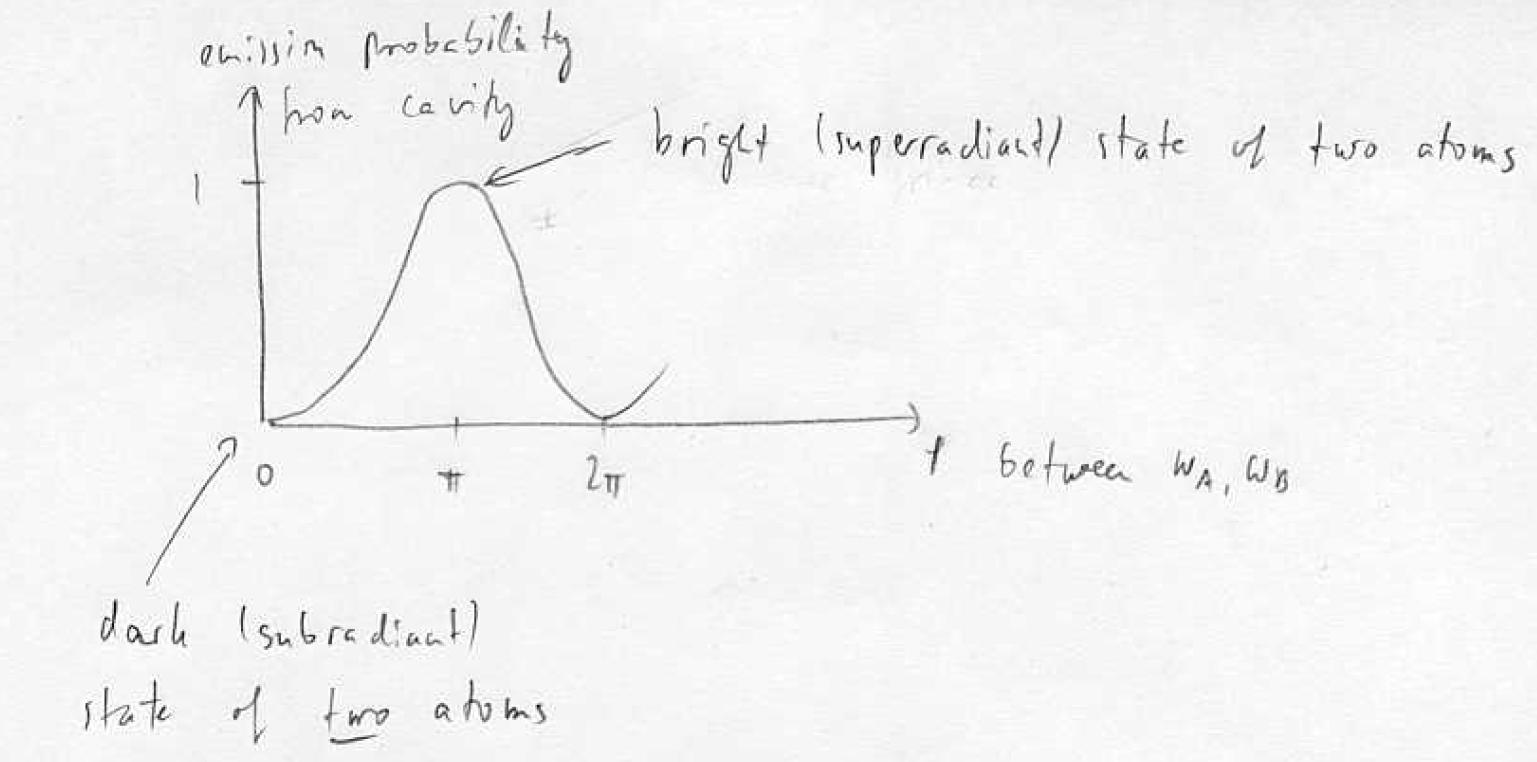

Verification and entanglement:

well-defined phase must exist

How to verify? Simultaneous readout, super and sub radiant states

The dipole moments (emitted fields on the ge transition) of the two atoms can interfere.

Interference fringe can only be observed if state is entangled. Fringe is due to interference if dipole moments between <underline> <attributes> </attributes> different </underline> atoms.

On the "magic" of dark-state adiabatic transfer

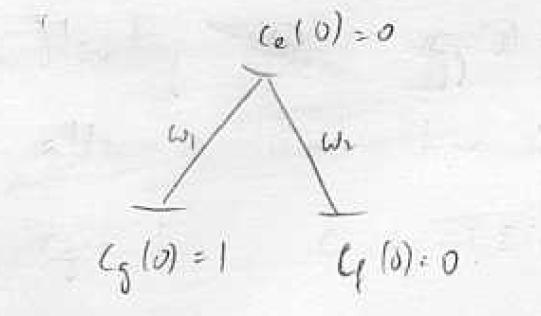

How is it that we can transfer the population completely form state |g> to state |f> through the state |e> while keeping the unstable state |e> unpopulated? (The correct statement is "...while keeping the population of |e> negligibly small"). This is possible through coherence-interference: n resonance the eqs of motion for the amplitude read

For adiabatic transfer we have and amplitude flow as

So we see how |f> accumulates amplitude because it arrives there always with the same phase factor -1, whereas the flow back from |f> into |e> leads to a destructive interference in |e> with the amplitude flow from |g>, keeping the amplitude in |e> small at all times, while the amplitude on |f> keeps growing. If the state |f> were to acquire a random phase <underline> <attributes> </attributes> relative to |g> </underline> due to some other interaction, then the constructive interference leading to the accumulation of amplitude in |f> and the destructive interference in |e> would not work. The dark state transfer requires g-f coherence.

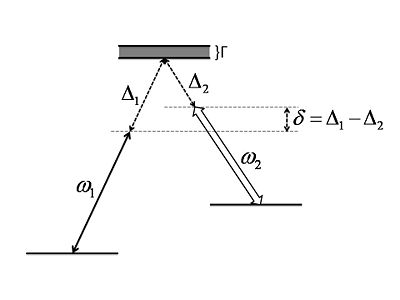

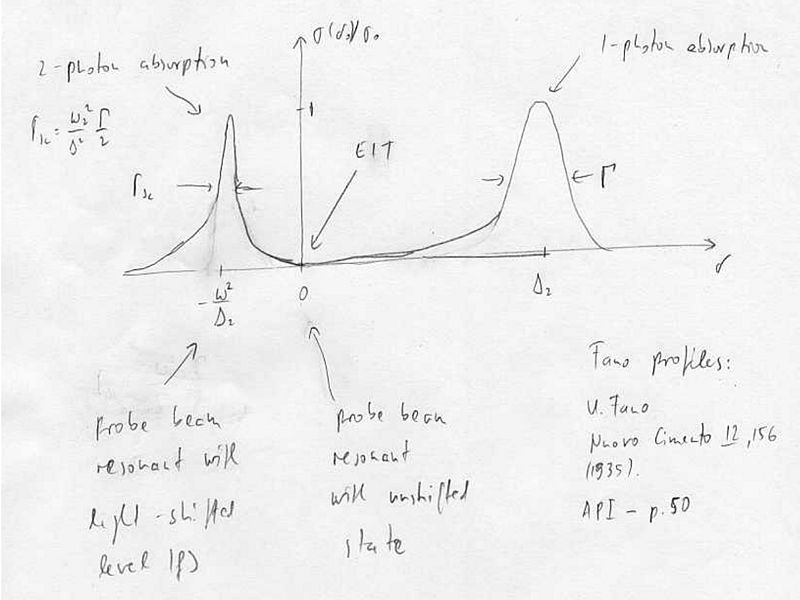

Two-phase absorption, Fano profiles

Let us assume large one-photon detuning, , weak probe and strong control field (we also define the two-photon detuning ).

In this limit analytic expressions for the absorption cross section for beam and the refractive index seen by beam exist, e.g. [Muller et al., PRA 56, 2385 (1997)]

The refractive index is given by:

where is the atomic density, .

For zero ground-state linewidth (decoherence between the ground-states) where is the resonant cross-section, and .

The absorption cross section for :

This is like a ground state coupling to one narrow and one wide excited state, except that there is EIT in between because both states decay to the same continuum.

At , we have one-photon absorption, which is a two-photon scattering process:

At , two-photon absorption, which is (at least) four-photon scattering process:

For the EIT condition , there is no coupling to the excited state, and the refractive index is zero. In the vicinity of EIT, there is steep dispersion, resulting in a strong alteration of the group velocity of light slowing and stopping light.

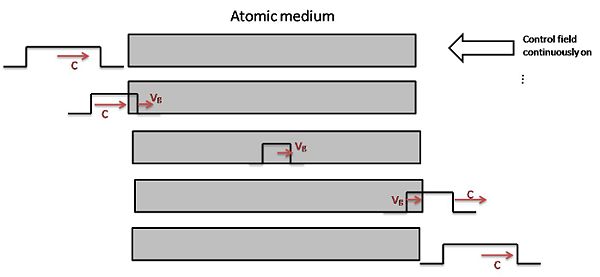

Slow light, adiabatic changes of velocity of light

The group velocity of light in the presence of linear dispersion is given by [Harris and Hau, PRL 82, 4611 (1999)]

for light at frequency .

A strong linear dispersion with positive slope near EIT then corresponds to very slow light.

As , the electric field is unchanged so the power per area also remains unchanged.

Due to slowed group velocity, the pulse is compressed in the medium. As a consequence, the energy density is increased, and the light is partly in the form of an atomic excitation (coherent superposition of the ground states, although most of the energy is exchanged to the control field).

For sufficiently small , the velocity of light may be very small, down to a few m/s [L.V. Hau, S.E. Harris et al., Nature 397, 594 (1999)], as observed in a BEC. Reduced group velocity can also be observed in room-temperature experiment if the setup is Doppler free (co-propagating probe and control fields and ) (otherwise only a small velocity class satisfies the two-photon resonance condition).

If we change control field adiabatically while the pulse is inside the medium, we can coherently stop light, i.e. convert it into an atomic excitation or spin wave. With the reverse process we can then convert the stored spin-wave back into the original light field. The adiabatic conversion is made possible by the finite splitting between bright and dark states. In principle, all coherence properties and other (qm) features of the light are maintained, and it is possible to store non-classical states of light by mapping photon properties one-to-one onto quantized spin waves. We will learn more about these quanta called "dark-state polaritons" once we have introduced Dicke states. Is it possible to make use of EIT for, e.g. atom detection without absorption? Answer: no improvement for such linear processes. However: improvement for non-linear processes is possible.

Superradiance

Assume that two identical atoms, one in its ground and the other in its excited state, are placed within a distance of each other. What happens?

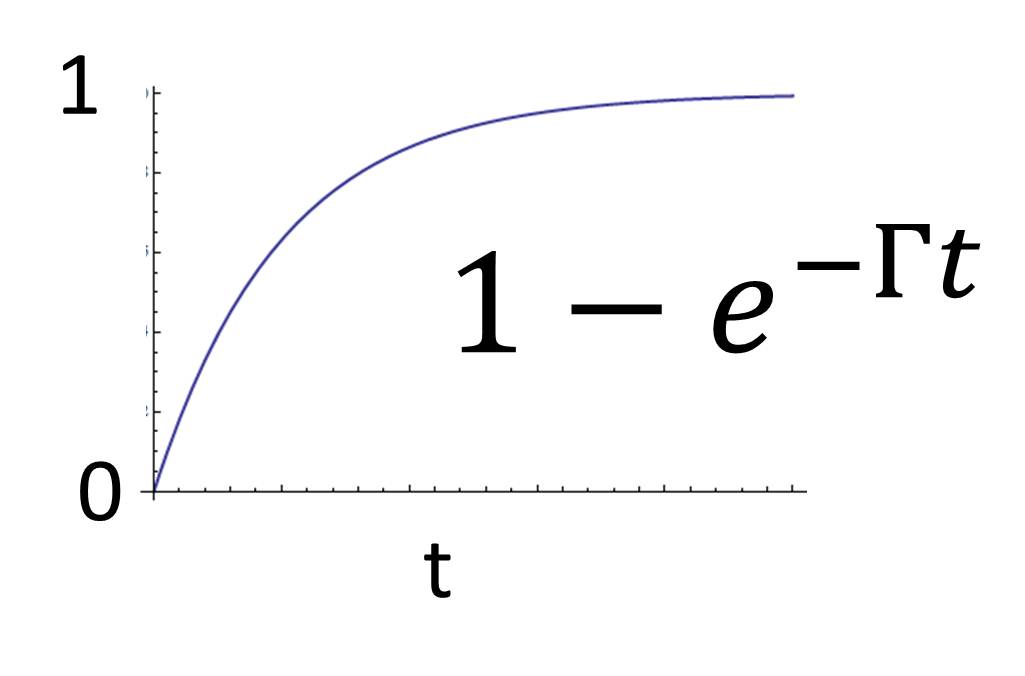

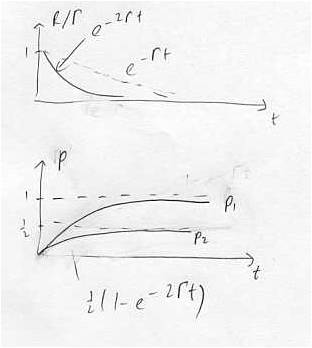

For a single atom we have, for the emission rate at time t is (product of the spontaneous emission rate and occupation probability). Thus, the emission probability to have emitted a photon by time t is

(eqtn:superradiance1)

What about two atoms? It turns out that the correct answer is

(eqtn:superradiance2)

(eqtn:superradiance3)

The photon is emitted with the same initial rate, but has only probability of being emitted at all! How can we understand this? The interaction Hamiltonian is (classically):

(eqtn:superradiance5)

In QED:

(eqtn:superradiance6)

with

Lecture XXVI

Superradiance, continued

Now we can write the initial state as:

where

and

The initial state has a 50% probability to be the sub-radiant state, hence the system has a 50% probability of not decaying. The set of four states can be organized into a triplet and a singlet:

The state is "dark" in that it does not decay under the action of the Hamiltonian V. The matrix elements between the states, indicated by arrows, are expressed in units of the single atom coupling .

Just as we can identify the two-level system , with a (pseudo)spin , we can identify the triplet and singlet states with , and write

Since V conserves parity (exchange of the two atoms), there is no coupling between singlet and triplet states. (This is no longer true when we consider spatially extended samples).

Supperradiance in N atoms

First look at N spins in a magnetic field (NMR)

Dipole moment: , power radiation . There is N times more enhancement over N.

For N excited atoms, we usually regard the atoms as independent. Therefore, power radiation scales as N.

BUT: All two-level systems are equivalent. Which picture is correct?

Answer: There is an important distinction between sample size and sample size . For sample size , which is usually the case for optical transitions, the particles can be treated independently. For sample size Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \ll \lambda} , all particles interact with a common radiation field and thus cannot be treated independently.

The coherence in spontaneous emission for N (localized) atoms requires two assumptions:

1. No interaction between atoms 2. Emitted photons (NOT the atoms) are indistinguishable. The particle symmetry (Bosons, Fermions) is irrelevant.

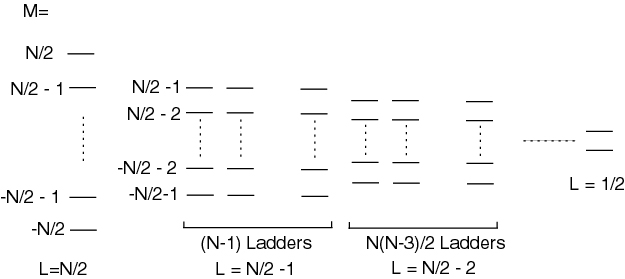

The Dicke states, equivalent to the states obtained by summing N spin Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \frac{1}{2}} particles, are

Interaction with em field through Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle S_+} , Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle S_-}

Matrix element responsible for spontaneous emission:

Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle <S,M-1|S_-|S,M>=\sqrt{(S-M+1)(S+M)}}

Note matrix element only couple within one ladder. For single particle, Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle S=M=\frac{1}{2}\Rightarrow<S,M-1|S_-|S,M>=1} . Rate (or intensity I) of radiation relative to a single particle:Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle I=(S-M+1)(S+M)}

Let's look at Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle S=\frac{N}{2}}

1.

Let us look at the leftmost (symmetric) ladder. Near the middle of the Dicke-ladder, Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle M\simeq 0} , the matrix element is Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle <V> \simeq \sqrt {\frac{N}{2}(\frac{N}{2}-1)}g\simeq N g. } The emission rate is proportional to , i.e. the rate is quadratic in atom number.

Classically, that is not too surprising: we have N dipoles oscillating in phase, which corresponds to a dipole Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle D=Nd} , the emission is proportional to Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle D^2=N^2d^2} . However, the Dicke states have Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle <D>=0} and nevertheless macroscopic emission. How do we see this? In the Bloch sphere, for the angular momentum representation the coherent state Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle |L=N/2,M=-N/2>=|g...g>} corresponds to all atoms in the ground state.

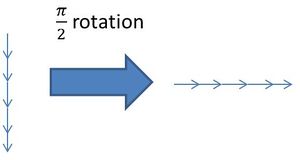

A field that symmetrically couples to all atoms (e.g. Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \frac{\pi }{2},\pi } pulse) acts only within the completely symmetric Hilbert space Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle L=N/2} . This space consists of states like Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle (\cos \theta |e>+\sin \theta e^{i\phi }|g>)^ N} , corresponding to rotations of the state Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle |g...g>} around some axis on the Bloch sphere.

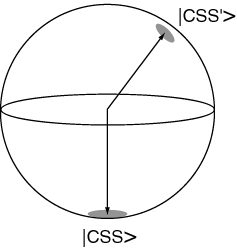

The states obtained by rotations of the state Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle |g...g>} by symmetric operations that act on all individual atoms independently, i.e. of the form Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle |g>\rightarrow \cos \theta |e>+e^{i\phi }\sin \theta |g>} , are called coherent spin states (CSS). They are represented by a vector on the Bloch sphere with uncertainties Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \sqrt {\frac{L}{2}}} in directions perpendicular to the Bloch vector.

If we prepare a system in the CSS corresponding to a slight angle away form Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \theta =0} near Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle |e...e>=|L=N/2,M=N/2>} , then classically it will obey the eqs of motion of an inverted pendulum, and fall down along the Bloch sphere. (This can be shown using the classical analogy with a field.)

So what happens if we prepare the state Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle |M=+L>=|e...e>} ? Does it:

a. evolve down along the Dicke ladder maintaining (but Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle <D^2>\neq 0} )?

b. fall like a Bloch vector along some angle chosen by vacuum fluctuations?

Answer: there is no way of telling unless you prepare a specific experiment. If we detect (with unity quantum efficiency) the emitted photons, then each detection projects the system one step down along the Dicke ladder, and Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle <D>=0} .

If we measure the phase of the emitted light, say with some heterodyne technique, then we find that the system evolves as a Bloch state.

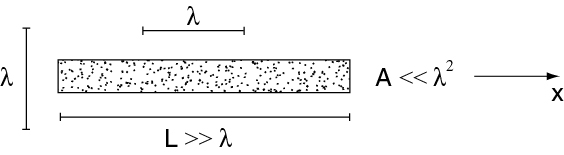

Dicke states of extended samples

Consider an elongated atomic sample

such that a preferential mode (along x) is defined. Then we can define Dicke states with respect to that mode as

Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle |L,M=-L>=|g...g>}

Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle |L,M=-L+1>=\frac{1}{\sqrt {N}}(e^{i k x_1}|eg...g>+e^{ikx_2}|geg...>+...+e^{ikx_N}|g...ge>)}

etc.

Then one can easily see that the phase factors are such that the interaction Hamiltonian

Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle V=\Sigma _ i\vec{d_ i}\cdot \vec{E}(\vec{x_ i})=\Sigma _ i\vec{d}\cdot \vec{E}_0e^{i\kappa x_ i}}

is such that the Dicke ladder has the same couplings as before, i.e. superradiance occurs. However, emission along a direction other than the preferred mode now leads to diagonal couplings between the Dicke ladders , since emission along some other direction with operator Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle e^{i\vec{k}\cdot \vec{r}}} does not preserve the symmetry of the state with respect to permutations of the atoms. However, if the atom number along the preferred direction is large enough, superradiance still occurs. The condition for Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle A\ll\lambda^2} is Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle N\geq 2} , but for the condition is Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \frac{N\lambda ^2}{A}>1} . This is exactly the condition for sufficient optical gain in an inverted system for optical amplification (lasing) to occur, since Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \lambda ^2} is the stimulated emission cross section for an atom in Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle |e>} .

Observation in a BEC, in multimode optical cavities.

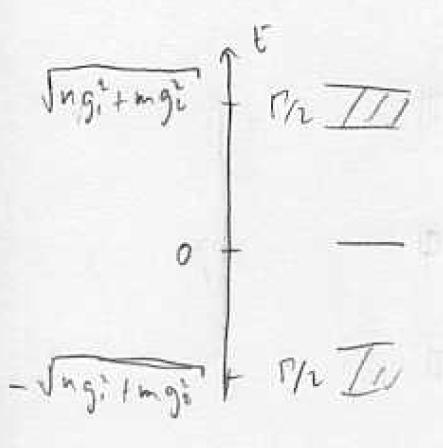

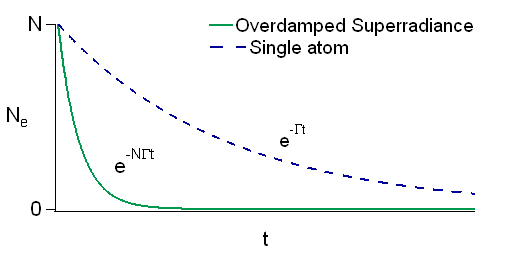

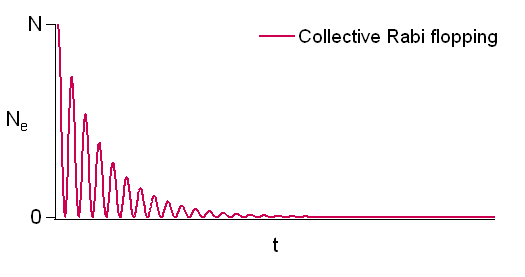

Oscillating and overdamped regimes of superradiance

The photon leaves the sample in a time Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \frac{L}{c}} . If , then the damping is faster than Rabi flopping, and we are in the rate equation limit where the emission proceeds as Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \frac{(\sqrt {N}g)^2}{c/L}=\frac{Ng^2L}{c}} , rather than as emission by independent atoms that would decay as Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \frac{g^2}{c/L}} . If Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \sqrt {N}g>\frac{c}{L}} , then Rabi flopping occurs during the decay.

Note:Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \Gamma = g^2L/C} .

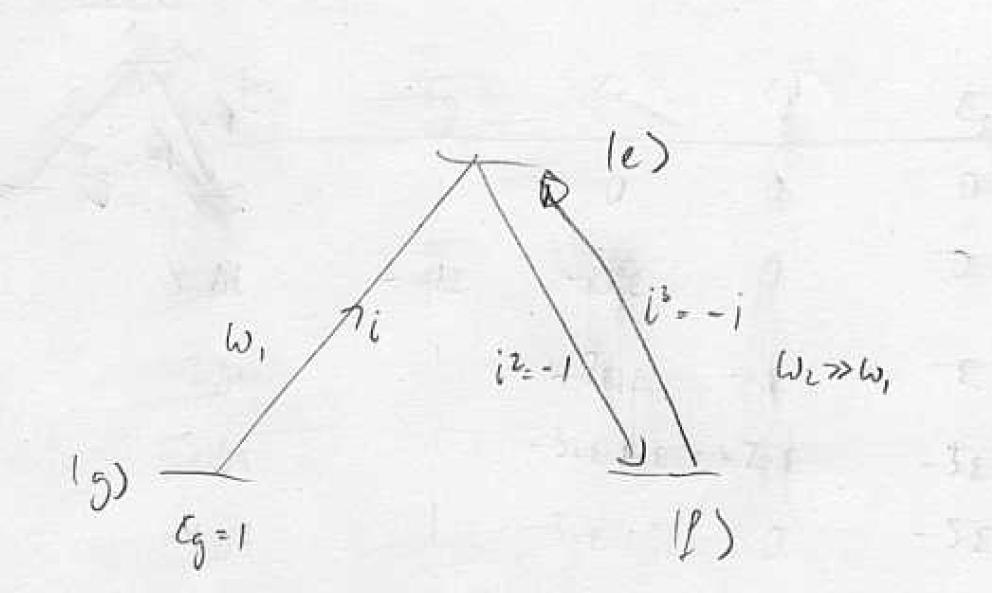

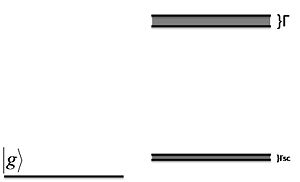

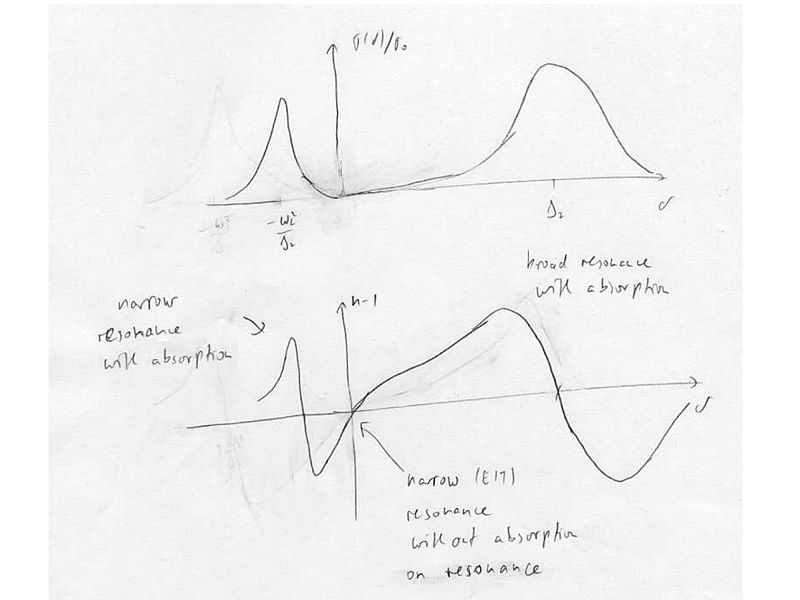

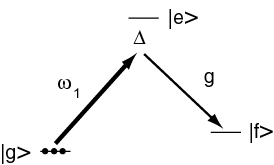

Raman Superradiance

In the limit of large and low saturation Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \omega _1\ll \Delta } , we can eliminate the excited state and have an effective system.

Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \Gamma_{sc}=\frac{\omega _1^2}{\Delta ^2}\frac{r}{2}}

We can now adjust the linewidth Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \Gamma_{sc}} via Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \omega _1} and also make the excited state Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle |e'>} suddenly stable by turning off Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \omega _1} . In fact we can switch ground and excited states by applying a laser beam on the other Raman leg instead.

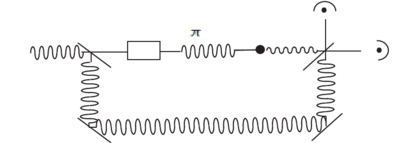

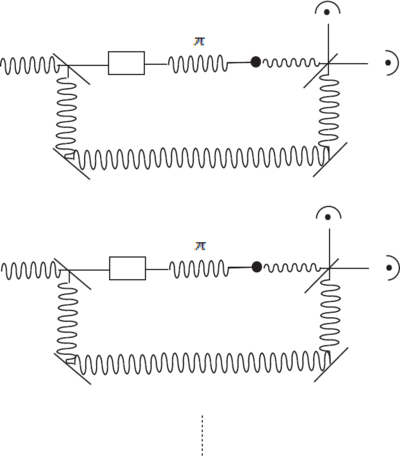

Storing light, catching photons

When we consider a quantized field on the transition, there is a family of dark states, corresponding to Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle n=0,1,2,...} excitations

Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle |D,n>=\Sigma ^ n_{k=0}\sqrt {\frac{n!}{k!(n-k)!}}\frac{(-g)^{k }N^{\frac{k }{2}}\Omega ^{n-k }}{(Ng^2+\Omega ^2)^{\frac{n}{2}}}|n-k >_{\mathrm{photons}}|L=\frac{N}{2},M=-L+k >}

(Lukin, Yelin, and Fleischhauer PRL 84, 4233 (2000)).

When Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \Omega \gg Ng^2} , these states are purely photonic. When Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \omega \ll Ng^2} , these states are purely atomic excitations.

Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \Omega \gg Ng^2 :|D,n> \rightarrow |n>_{\mathrm{photons}}|L,M=-L>_{\mathrm{atoms}} }

Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \Omega \ll Ng^2 : |0>_{\mathrm{photons}}|L,M=-L+n>_{\mathrm{atoms}}}

In general, these excitations n=0,1,2,... are called dark state polaritons. They are a mixture of photonic excitations and spin-wave excitations.

By adiabatically changing Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \Sigma \rightarrow 0} after the pulse has entered the medium, we can map any photonic state Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle |\psi >_{\mathrm{photon}}=\Sigma c_i|i>_{\mathrm{photon}}} onto a spin wave, store it and map it back onto a light-field by turning on the coupling laser Failed to parse (MathML with SVG or PNG fallback (recommended for modern browsers and accessibility tools): Invalid response ("Math extension cannot connect to Restbase.") from server "https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/":): {\displaystyle \Omega } again.

![{\displaystyle \langle {\hat {\sigma }}_{x}\rangle =Tr[\rho {\hat {\sigma }}_{x}]=Tr\left({\begin{array}{cc}{\frac {1}{2}}e^{-i\omega _{L}t}&{\frac {1}{2}}\\{\frac {1}{2}}&{\frac {1}{2}}e^{i\omega _{L}t}\end{array}}\right)=\cos \omega _{L}t.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/2a9d0aea923dce7dc4a7623215831fbc0af38ef5)