imported>Wikipost |

imported>Ketterle |

| (23 intermediate revisions by one other user not shown) |

| Line 1: |

Line 1: |

| − | == Interferometry and metrology ==

| |

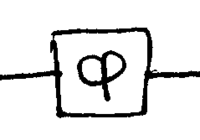

| | Suppose you are given a phase shifter of unknown <math>\phi</math>: | | Suppose you are given a phase shifter of unknown <math>\phi</math>: |

| | ::[[Image:chapter2-quantum-light-part-5-interferometry-l7-phase.png|thumb|200px|none|]] | | ::[[Image:chapter2-quantum-light-part-5-interferometry-l7-phase.png|thumb|200px|none|]] |

| − | \noindent

| |

| | How accurately can you determine <math>\phi</math>, given a certain time, and | | How accurately can you determine <math>\phi</math>, given a certain time, and |

| | laser power? | | laser power? |

| Line 13: |

Line 11: |

| | measurement techniques generalizes to a wide range of metrology | | measurement techniques generalizes to a wide range of metrology |

| | problems, but a common challenge the need to reduce loss. | | problems, but a common challenge the need to reduce loss. |

| | + | |

| | + | |

| | + | <categorytree mode=pages style="float:right; clear:right; margin-left:1ex; border:1px solid gray; padding:0.7ex; background-color:white;" hideprefix=auto>8.422</categorytree> |

| | + | |

| | === Shot noise limit === | | === Shot noise limit === |

| − | The Poisson distribution of photon number in coherent (laser) light

| + | |

| − | contributes an uncertainty of <math>\Delta n \sim\sqrt{n}</math> to optical

| + | {{:Interferometer shot noise limit}} |

| − | measurements. It is therefore reasonable to anticipate that with <math>n</math>

| + | |

| − | photons, the uncertainty <math>\Delta \phi</math> with which an unknown phase

| |

| − | <math>\phi</math> can be determined might be bounded below by <math>\Delta \phi \geq

| |

| − | 1/\sqrt{n}</math>, based on the heuristic that <math>\Delta n \Delta \phi \geq

| |

| − | 1</math>. Such a limit is known as being due to shot noise, arising

| |

| − | from the particle nature of photons, as we shall now see rigorously.

| |

| − | Consider a Mach-Zehnder interferometer constructed from two 50/50

| |

| − | beamsplitters, used to measure <math>\phi</math>:

| |

| − | ::[[Image:chapter2-quantum-light-part-5-interferometry-l7-mzi.png|thumb|306px|none|]]

| |

| − | \noindent

| |

| − | Let us analyze this interferometer, first by using a traditional

| |

| − | quantum optics approach in the Heisenberg picture, and second by using

| |

| − | single photons in the Schrodinger picture.

| |

| − | Previously, we've defined the unitary transform for a quantum

| |

| − | beamsplitter as being a rotation about the <math>\hat{y}</math> axis, so as to

| |

| − | avoid having to keep track of factors of <math>i</math>. For variety, let's now

| |

| − | use a different definition; nothing essential will change.

| |

| − | Let the 50/50 beamsplitter transformation be

| |

| − | :<math>

| |

| − | B = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \left[ \begin{array}{cc}{1}&{-i}\\{-i}&{1}\end{array}\right]

| |

| − | \,.

| |

| − | </math>

| |

| − | This acts on <math>[a,b]^T</math> to produce operators describing the output of

| |

| − | the beamsplitter; in particular,

| |

| − | :<math>

| |

| − | \left[ \begin{array}{c}{a-ib}\\{b-ia}\end{array}\right] = B \left[ \begin{array}{c}{a}\\{b}\end{array}\right]

| |

| − | \,.

| |

| − | </math>

| |

| − | Similarly, the phase shifter acting on the mode operators performs

| |

| − | :<math>

| |

| − | P = \left[ \begin{array}{cc}{1}&{0}\\{0}&{e^{i\phi}}\end{array}\right]

| |

| − | \,.

| |

| − | </math>

| |

| − | The Mach-Zehnder transform is thus

| |

| − | :<math>\begin{array}{rcl}

| |

| − | U &=& B P B

| |

| − | \\

| |

| − | &=& \frac{1}{2} \left[ \begin{array}{cc}{1}&{-i}\\{-i}&{1}\end{array}\right]

| |

| − | \left[ \begin{array}{cc}{1}&{0}\\{0}&{e^{i\phi}}\end{array}\right]

| |

| − | \left[ \begin{array}{cc}{1}&{-i}\\{-i}&{1}\end{array}\right]

| |

| − | \\ &=& -i e^{i\phi/2} \left[ \begin{array}{cc}{\sin(\phi/2)}&{\cos(\phi/2)}\\{\cos(\phi/2)}&{-\sin(\phi/2)}\end{array}\right]

| |

| − | \,.

| |

| − | \end{array}</math>

| |

| − | The way we have defined these transformations here, the output modes

| |

| − | of the interferometer, <math>c</math> and <math>d</math>, are

| |

| − | :<math>

| |

| − | \left[ \begin{array}{c}{c}\\{d}\end{array}\right] = U \left[ \begin{array}{c}{a}\\{b}\end{array}\right]

| |

| − | \,.

| |

| − | </math>

| |

| − | We are interested in the difference between the photon numbers

| |

| − | measured at the two outputs, <math>M = ( d^\dagger d- c^\dagger c)/2</math>, where the

| |

| − | extra factor of two is introduced for convenience. We find

| |

| − | :<math>\begin{array}{rcl}

| |

| − | c^\dagger c &=& \sin^2 \frac{\phi}{2} a^\dagger a + \cos^2 \frac{\phi}{2} b^\dagger b

| |

| − | + \sin \frac{\phi}{2} ( a^\dagger b + b^\dagger a)

| |

| − | \\

| |

| − | d^\dagger d &=& \cos^2 \frac{\phi}{2} a^\dagger a + \sin^2 \frac{\phi}{2} b^\dagger b

| |

| − | - \sin \frac{\phi}{2} ( a^\dagger b + b^\dagger a)

| |

| − | \end{array}</math>

| |

| − | The measurement result <math>M</math> is thus

| |

| − | :<math>

| |

| − | M = ( a^\dagger a - b^\dagger b ) \cos\phi - ( a^\dagger b+ b^\dagger a) \sin\phi

| |

| − | \,.

| |

| − | </math>

| |

| − | Define <math>X = a^\dagger a - b^\dagger b </math>, and <math>Y = a^\dagger b+ b^\dagger a</math>. Recognizing that

| |

| − | <math>X</math> is the difference in photon number between the two output arms,

| |

| − | and recalling that this is the main observable result from changing

| |

| − | <math>\phi</math>, we identify the signal we wish to see as being <math>X</math>. Ideally,

| |

| − | the output signal should go as <math>\cos\phi</math>. The signal due to <math>Y</math> goes

| |

| − | as <math>\sin\phi</math>, and we shall see that this is the noise on the signal.

| |

| − | The average output signal <math> \langle X{\rangle}</math>, as a function of <math>\phi</math>, looks like this:

| |

| − | ::[[Image:chapter2-quantum-light-part-5-interferometry-l7-balance-point.png|thumb|200px|none|]]

| |

| − | \noindent

| |

| − | Note that if our goal is to maximize measurement sensitivity to

| |

| − | changes in <math>\phi</math>, then the best point to operate the interferometer

| |

| − | at is around <math>\phi=\pi/2</math>, since the slope <math>d \langle x{\rangle}/d\phi</math> is largest

| |

| − | there. At this operating point, if the interferometer's inputs have

| |

| − | laser light coming into only one port, then the outputs have equal

| |

| − | intensity; thus, the interferometer is sometimes said to be

| |

| − | "balanced" when <math>\phi=\pi/2</math>.

| |

| − | What is the uncertainty in our measurement of <math>\phi</math>, derived from the

| |

| − | observable <math>M</math>? By propagating uncertainties, this is

| |

| − | :<math>

| |

| − | {\langle}\Delta\phi^2 \rangle = \frac{{\langle}\Delta M^2{\rangle}}

| |

| − | {\left|\frac{\partial \langle M{\rangle}}{\partial\phi}\right|^2}

| |

| − | \,,

| |

| − |

| |

| − | </math>

| |

| − | where

| |

| − | :<math>

| |

| − | \frac{\partial \langle M{\rangle}}{\partial\phi}

| |

| − | =

| |

| − | -X \sin\phi - Y\cos\phi

| |

| − | \,.

| |

| − | </math>

| |

| − | Let <math>\phi=\pi/2</math>, such that <math>M=Y</math>, and <math>\partial M/\partial\phi = -X</math>.

| |

| − | For a coherent state input, <math>|\psi_{in} \rangle = |\alpha{\rangle}|0{\rangle}</math>, we find

| |

| − | :<math>\begin{array}{rcl}

| |

| − | \langle X \rangle &=& \langle 0|{\langle}\alpha|( a^\dagger a - b^\dagger b )|\alpha{\rangle}|0{\rangle}

| |

| − | \\

| |

| − | &=& |\alpha|^2

| |

| − | \\

| |

| − | &=& n

| |

| − | \,,

| |

| − | \end{array}</math>

| |

| − | if we define <math>n = |\alpha|^2</math> as the input state mean photon number.

| |

| − | Also,

| |

| − | :<math>\begin{array}{rcl}

| |

| − | \langle Y \rangle = \langle 0|{\langle}\alpha| ( a^\dagger b+ b^\dagger a)|\alpha{\rangle}|0 \rangle = 0

| |

| − | \,.

| |

| − | \end{array}</math>

| |

| − | This is consitent with our intuition: the signal should go as <math>\sim

| |

| − | n</math>, and the undesired term goes as <math>Y</math>, so it is good that is small on

| |

| − | average. However, there are nontrivial fluctuations in <math>Y</math>, because

| |

| − | :<math>

| |

| − | \langle Y^2 \rangle = \langle a^\dagger b a^\dagger b + a^\dagger b b^\dagger a + b^\dagger a b^\dagger

| |

| − | a + b^\dagger a a^\dagger b{\rangle}

| |

| − | \,,

| |

| − | </math>

| |

| − | and <math> \langle a^\dagger b b^\dagger a \rangle = \langle a^\dagger a(1+ b^\dagger b ){\rangle}</math> is nonzero for the

| |

| − | coherent state! Specifically, the noise in <math>Y</math> is

| |

| − | :<math>

| |

| − | \langle Y^2 \rangle = |\alpha|^2 = n

| |

| − | \,,

| |

| − | </math>

| |

| − | and thus the variance in the measurement result is

| |

| − | :<math>

| |

| − | {\langle}\Delta M^2 \rangle = \langle Y^2 \rangle - \langle Y{\rangle}^2 = |\alpha|^2 = n

| |

| − | \,.

| |

| − | </math>

| |

| − | From Eq.(\ref{eq:l7-dphi}), it follows that the uncertainty in <math>\phi</math>

| |

| − | is therefore

| |

| − | :<math>

| |

| − | {\langle}\Delta\phi \rangle =

| |

| − | \frac{\sqrt{{\langle}\Delta M^2{\rangle}}}

| |

| − | {\left|\frac{\partial \langle M{\rangle}}{\partial\phi}\right|}

| |

| − | = \frac{\sqrt{n}}{n} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{n}}

| |

| − | \,.

| |

| − | </math>

| |

| − | This is a very reasonable result; as the number of photons used

| |

| − | increases, the accuracy with which <math>\phi</math> can be determined increases

| |

| − | with <math>\sqrt{n}</math>. The improvement arises because greater laser power

| |

| − | allows better distinction between the signals in <math>c</math> and <math>d</math>.

| |

| − | Another way to arrive at the same result, using single photons, gives

| |

| − | an alternate interpretation and different insight into the physics.

| |

| − | As we have seen previously, acting on the <math>|01{\rangle}</math>, <math>|10{\rangle}</math>

| |

| − | "dual-rail" photon state, a 50/50 beamsplitter performs a

| |

| − | <math>R_y(\pi/2)</math> rotation, and a phase shifter performs a <math>R_z(\phi)</math>

| |

| − | rotation. The Mach-Zehnder interferometer we're using can thus be

| |

| − | expressed as this transform on a single qubit:

| |

| − | ::[[Image:chapter2-quantum-light-part-5-interferometry-l7-qubit-mzi.png|thumb|200px|none|]]

| |

| − | \noindent

| |

| − | where the probability of measuring a single photon at the output is

| |

| − | <math>P</math>. Walking through this optical circuit, the states are found to be

| |

| − | :<math>\begin{array}{rcl}

| |

| − | |\psi_1 \rangle &=& \frac{|0{\rangle}+|1{\rangle}}{\sqrt{2}}

| |

| − | \\

| |

| − | |\psi_2 \rangle &=& \frac{|0{\rangle}+e^{i\phi} |1{\rangle}}{\sqrt{2}}

| |

| − |

| |

| − | \\

| |

| − | |\psi_3 \rangle &=& \frac{1-e^{i\phi}}{2} |0 \rangle +

| |

| − | \frac{1+e^{i\phi}}{2} |1{\rangle}

| |

| − | \,,

| |

| − | \end{array}</math>

| |

| − | such that

| |

| − | :<math>

| |

| − | P = \frac{1+\cos\phi}{2}

| |

| − | \,.

| |

| − | </math>

| |

| − | Repeating this <math>n</math> times (so that we use the same average number of

| |

| − | photons as in the coherent state case), we find that the standard

| |

| − | deviation in <math>P</math> is

| |

| − | :<math>

| |

| − | \Delta P = \sqrt{\frac{p(1-p)}{n}} = \frac{\sin\phi}{2\sqrt{n}}

| |

| − | \,.

| |

| − | </math>

| |

| − | Given this, the uncertainty in <math>\phi</math> is

| |

| − | :<math>

| |

| − | \Delta\phi = \frac{\Delta\phi}

| |

| − | {\left| \frac{dP}{d\phi} \right|} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{n}}

| |

| − | \,.

| |

| − | </math>

| |

| − | This is the same uncertainty as we obtained for the coherent state

| |

| − | input, but the physical origin is different. Now, we see the noise as

| |

| − | being due to statistical fluctuations of a Bernoulli point process,

| |

| − | one event at a time. The <math>\sqrt{n}</math> noise thus comes from the amount

| |

| − | of time the signal is integrated over (assuming a constant rate of

| |

| − | photons). The noise is simply shot noise.

| |

| | === Heisenberg limit: entanglement === | | === Heisenberg limit: entanglement === |

| − | The shot noise limit we have just seen, however, is not fundamental.

| + | |

| − | Here is a simple argument that something better should be possible.

| + | {{:Interferometer Heisenberg limit}} |

| − | Recall that the desired signal at the output of our Mach-Zehnder

| + | |

| − | interferometer is <math>X= a^\dagger a - b^\dagger b </math>, and the noise is <math>Y= a^\dagger b+ b^\dagger a</math>.

| |

| − | If the inputs have <math> a^\dagger a =n</math> and <math> b^\dagger b =0</math>, and if <math>Y</math> were zero, then

| |

| − | the measured signal would be <math>n\cos\phi</math>. And at the balanced

| |

| − | operating point <math>\phi=\pi/2</math>,

| |

| − | :<math>

| |

| − | \frac{|\Delta m|}{\Delta \phi} = n\sin\phi \leq n

| |

| − | \,.

| |

| − | </math>

| |

| − | Thus, if the smallest photon number change resolvable is <math>\Delta m=1</math>,

| |

| − | then <math>n\Delta\phi \geq 1</math>, from which it follows that

| |

| − | :<math> | |

| − | \Delta \phi \geq \frac{1}{n}

| |

| − | \,.

| |

| − | </math>

| |

| − | This is known as the "Heisenberg limit" on interferometry. There

| |

| − | are some general proofs in the literature that such a limit is the

| |

| − | best possible on interferometry. It governs more than just

| |

| − | measurements of phase shifters; gyroscopes, mass measurements, and

| |

| − | displacement measurements all use interferometers, and obey a

| |

| − | Heisenberg limit.

| |

| − | The argument above only outlines a sketch for why <math>1/n</math> might be an

| |

| − | achievable limt, versus <math>1/\sqrt{n}</math>; it assumes that the noise <math>Y</math>

| |

| − | can be made zero, however, and does not provide a means for

| |

| − | accomplishing this in practice.

| |

| − | Many ways to reach the Heisenberg limit in interferometry are now

| |

| − | known. Given the basic structure of a Mach-Zehnder interferometer,

| |

| − | ::[[Image:chapter2-quantum-light-part-5-interferometry-l7-generic-mzi.png|thumb|306px|none|]]

| |

| − | \noindent

| |

| − | one can consider changing the input state <math>|\psi_{in}{\rangle}</math>, changing the

| |

| − | beamsplitters, or changing the measurement.

| |

| − | Common to all of these approaches is the use of entangled states. How

| |

| − | entanglement makes Heisenber-limited interferometry possible can be

| |

| − | demonstrated by the following setup. Let us replace the beamsplitters

| |

| − | in the Mach-Zehnder interferometer with entangling and dis-entangling

| |

| − | devices:

| |

| − | ::[[Image:chapter2-quantum-light-part-5-interferometry-l7-entangled-mzi.png|thumb|200px|none|]]

| |

| − | \noindent

| |

| − | Conceptually, the unusual beamsplitters may be the nonlinear

| |

| − | Mach-Zehnder interferometers we discussed in Section~2.3. They may

| |

| − | also be described by simple quantum circuits, using the Hadamard and

| |

| − | controlled-{\sc not} gate; for two qubits, the circuit is

| |

| − | ::[[Image:chapter2-quantum-light-part-5-interferometry-l7-entangler1.png|thumb|200px|none|]]

| |

| − | \noindent

| |

| − | Note how the output is one of the Bell states. For three qubits, the

| |

| − | circuit is

| |

| − | ::[[Image:chapter2-quantum-light-part-5-interferometry-l7-entangler2.png|thumb|200px|none|]]

| |

| − | \noindent

| |

| − | This output state, <math>|000{\rangle}+|111{\rangle}</math> (suppressing normalization) is

| |

| − | known as a GHZ (Greenberger-Horne-Zeilinger) state. Straightforward

| |

| − | generalization leads to larger "Schrodinger cat" states

| |

| − | <math>|00\cdots0{\rangle}+|11\cdots 1{\rangle}</math>, using one Hadamard gate and <math>n</math>

| |

| − | controlled-{\sc not} gates. Note that the reversed circuit

| |

| − | unentangles the cat states to produce computational basis states.

| |

| − | The important feature of such <math>n</math>-qubit cat states, for our purpose,

| |

| − | is how they are transformed by phase shifters. A single qubit

| |

| − | <math>|0{\rangle}+|1{\rangle}</math> becomes <math>|0{\rangle}+e^{i\phi}|1{\rangle}</math>. Similarly, two entangled

| |

| − | qubits in the state <math>|00{\rangle}+|11{\rangle}</math>, when sent through two phase

| |

| − | shifters, becomes <math>|00{\rangle}+e^{2i\phi}|11{\rangle}</math>, since the phases add. And

| |

| − | <math>n</math> qubits in the state <math>|00\cdots 0{\rangle}+|11\cdots1{\rangle}</math> sent through <math>n</math>

| |

| − | phase shifters becomes <math>|00\cdots 0{\rangle}+e^{ni\phi}|11\cdots 1{\rangle}</math>.

| |

| − | When such a phase shifted state is un-entangled, using the reverse of

| |

| − | the entangling circuit, the <math>n</math> controlled-{\sc not} gates leave the

| |

| − | state <math>|00\cdots 0{\rangle}[ |0 \rangle + e^{ni\phi}|1 \rangle ]</math>, where the last <math>n-1</math>

| |

| − | qubits are left in <math>|0{\rangle}</math>, and the first qubit (the qubit used as the

| |

| − | control for the {\sc cnot} gates) is

| |

| − | :<math>

| |

| − | \frac{|0 \rangle + e^{ni\phi}|1{\rangle}}{\sqrt{2}}

| |

| − | \,.

| |

| − | </math>

| |

| − | Compare this state with that obtained from the single qubit

| |

| − | interferometer, Eq.(\ref{eq:l7-1qubitphase}); instead of a phase

| |

| − | <math>\phi</math>, the qubit now carries the phase <math>n\phi</math>. This means that the

| |

| − | probability <math>P</math> of measuring a single photon at the output becomes

| |

| − | :<math>

| |

| − | P = \frac{1+\cos(n\phi)}{2}

| |

| − | \,.

| |

| − | </math>

| |

| − | The standard deviation, from repeating this experiment, on average,

| |

| − | would be

| |

| − | :<math>

| |

| − | \Delta P = \sqrt{P(1-P)} = \frac{\sin(n\phi)}{2}

| |

| − | \,.

| |

| − | </math>

| |

| − | Using <math>dP/d\phi = -n\sin(n\phi)/2</math>, we obtain for the uncertainty in <math>\phi</math>,

| |

| − | :<math>

| |

| − | \Delta\phi = \frac{\Delta\phi}

| |

| − | {\left| \frac{dP}{d\phi} \right|} = \frac{1}{{n}}

| |

| − | \,,

| |

| − | </math>

| |

| − | which meets the Heisenberg limit.

| |

| | === Squeezed light interferometry === | | === Squeezed light interferometry === |

| − | Heisenberg-limited interferometry can also be accomplished using a

| + | |

| − | variety of states of light, including squeezed states we studied in | + | {{:Squeezed light interferometry}} |

| − | Section~2.2. Let us explore three configurations here.

| + | |

| − | Vacuum squeezed state input. Because squeezed states can move

| + | === Sensitivity to loss === |

| − | noise between the <math>x</math> and <math>p</math> quadratures, it is intuitively

| + | Entangled states, while very useful for a wide variety of tasks, |

| − | reasonable that a state with low phase noise could be used to provide

| + | including interferometry and metrology, are unfortunately generally |

| − | more accurate measurements of <math>\phi</math> than is possible with a coherent

| + | very fragile. In particular, entangled photon states degrade |

| − | state, which has equal noise in the two quadratures. | + | quickly with due to loss. |

| − | It might seem counter-intuitive, however, that we can get to the

| + | Consider, for example, the two-qubit state <math>|00{\rangle}+|11{\rangle}</math> (suppressing |

| − | Heisenberg limit by replacing not the coherent state input, but

| + | normalization). If one of theses photons goes through a |

| − | rather, the vacuum state, in the Mach-Zehnder interferometer. This

| + | mostly-transmitting beamsplitter, then the photon may be lost; let us |

| − | works because at the balanced operating point, the noise in the output

| + | say this happens with probability <math>\epsilon</math>. If a photon is lost, |

| − | is due to fluctuations entering in at the vacuum port. Before, we

| + | the state collapses into one with one remaining photon, say <math>|10{\rangle}</math>. |

| − | used <math>|\alpha{\rangle}|0{\rangle}</math> as input. Let us now replace this by

| + | This is a product state -- no longer entangled. It is not even a |

| − | :<math>

| + | superposition. No photon is lost with probability <math>(1-\epsilon)</math>. |

| − | |\psi_{in} = |\alpha \rangle |0_r{\rangle}

| + | Even worse, if both modes suffer potential loss of a photon, then |

| − | \,,

| + | no matter which mode looses a photon, the entangled state collapses; |

| − | </math> | + | this happens even if just one photon is lost. Thus, the |

| − | where <math>|0_r \rangle = S(r)|0{\rangle}</math> is a squeezed vacuum state. Recall that for

| + | state retains some entanglement only with probability |

| − | the balanced interferometer, the final uncertainty in the phase

| + | <math>(1-\epsilon)^2</math>. |

| − | measurement is

| + | And worst of all, if we have an <math>n</math>-photon cat state |

| | + | <math>|00\cdots0{\rangle}+|11\cdots 1{\rangle}</math>, and all modes are subject to loss |

| | + | <math>\epsilon</math>, then useful entanglement is retained only with probability |

| | + | <math>(1-\epsilon)^n</math>. Due to such loss, the phase measurement uncertainty |

| | + | of an entangled state interferometer will go as |

| | :<math> | | :<math> |

| − | {\langle}\Delta\phi \rangle = \frac{\sqrt{{\langle}\Delta Y^2{\rangle}}}{| \langle X{\rangle}|} | + | {\langle}\Delta\phi \rangle \sim \frac{1}{n(1-\epsilon)^n} |

| | \,, | | \,, |

| | </math> | | </math> |

| − | where <math>X = a^\dagger a - b^\dagger b </math>, and <math>Y = a^\dagger b+ b^\dagger a</math>. For the squeezed

| + | which is clearly undesirable. |

| − | vacu

| + | Some physical systems, however, naturally suffer very little loss, and |

| | + | can keep entangled states intact for long times. Photons |

| | + | unfortunately do not have that feature, but certain atomic states, |

| | + | such as hyperfine transitions, can be very long lived. Thus, many of |

| | + | the concepts derived in the context of quantum states of light, |

| | + | actually turn out to be more useful when applied to quantum states of |

| | + | matter. |

| | + | |

| | + | === Questions for thought === |

| | + | |

| | + | * Where does the random <math>1/\sqrt{n}</math> and <math>1/n</math> noise come from, in standard interferometry and in Heisenberg-limited interferometry? Is it from (a) the input state, (b) the beamsplitters, (c) projection noise in the final measurement? |

| | + | |

| | + | === References === |

| | + | |

| | + | * Squeezed light and multi-photon interferometry |

| | + | ** <refbase>5226</refbase> |

| | + | ** <refbase>5225</refbase> |

| | + | ** <refbase>5227</refbase> |

| | + | ** <refbase>5231</refbase> |

| | + | * Entangled / multi-photon interferometry with Atoms and Ions: |

| | + | ** <refbase>5222</refbase> |

| | + | ** <refbase>5232</refbase> |

| | + | |

| | + | [[Category:Quantum Light]] |

Suppose you are given a phase shifter of unknown  :

:

How accurately can you determine  , given a certain time, and

laser power?

In this section, we consider this basic measurement problem, and show

how the usual shot noise limit can be exceeded by using quantum states

of light, reaching a quantum limit determined by Heisenberg's

uncertainty principle. This limit is achieved using entanglement,

which can be realized using entangled multi-mode photons, or by a

variety of squeezed states. The physics behind such quantum

measurement techniques generalizes to a wide range of metrology

problems, but a common challenge the need to reduce loss.

, given a certain time, and

laser power?

In this section, we consider this basic measurement problem, and show

how the usual shot noise limit can be exceeded by using quantum states

of light, reaching a quantum limit determined by Heisenberg's

uncertainty principle. This limit is achieved using entanglement,

which can be realized using entangled multi-mode photons, or by a

variety of squeezed states. The physics behind such quantum

measurement techniques generalizes to a wide range of metrology

problems, but a common challenge the need to reduce loss.

Shot noise limit

The Poisson distribution of photon number in coherent (laser) light

contributes an uncertainty of  to optical

measurements. It is therefore reasonable to anticipate that with

to optical

measurements. It is therefore reasonable to anticipate that with  photons, the uncertainty

photons, the uncertainty  with which an unknown phase

with which an unknown phase

can be determined might be bounded below by

can be determined might be bounded below by  , based on the heuristic inequality

, based on the heuristic inequality  . Such a limit is known as being due to shot noise, arising

from the particle nature of photons, as we shall now see rigorously.

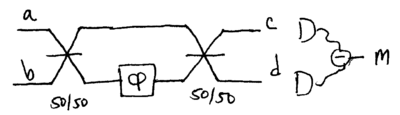

Consider a Mach-Zehnder interferometer constructed from two 50/50

beamsplitters, used to measure

. Such a limit is known as being due to shot noise, arising

from the particle nature of photons, as we shall now see rigorously.

Consider a Mach-Zehnder interferometer constructed from two 50/50

beamsplitters, used to measure  :

:

Let us analyze this interferometer, first by using a traditional

quantum optics approach in the Heisenberg picture, and second by using

single photons in the Schrodinger picture.

Sensitivity limit for Mach-Zehnder interferometer

Previously, we've defined the unitary transform for a quantum

beamsplitter as being a rotation about the  axis, so as to

avoid having to keep track of factors of

axis, so as to

avoid having to keep track of factors of  . For variety, let's now

use a different definition; nothing essential will change.

Let the 50/50 beamsplitter transformation be

. For variety, let's now

use a different definition; nothing essential will change.

Let the 50/50 beamsplitter transformation be

![{\displaystyle B={\frac {1}{\sqrt {2}}}\left[{\begin{array}{cc}{1}&{-i}\\{-i}&{1}\end{array}}\right]\,.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/4e2d43ef535ef4f670f31b7ce4cfe7a15c1890f8)

This acts on ![{\displaystyle [a,b]^{T}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/dcbe0f3bd3d712a823544cc4985e4dbd35b6967d) to produce operators describing the output of

the beamsplitter; in particular,

to produce operators describing the output of

the beamsplitter; in particular,

![{\displaystyle {\frac {1}{\sqrt {2}}}\left[{\begin{array}{c}{a-ib}\\{b-ia}\end{array}}\right]=B\left[{\begin{array}{c}{a}\\{b}\end{array}}\right]\,.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/3bcdd91d0e9a05a80b3165137ecd92a63b40bc81)

Similarly, the phase shifter acting on the mode operators performs

![{\displaystyle P=\left[{\begin{array}{cc}{1}&{0}\\{0}&{e^{i\phi }}\end{array}}\right]\,.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/3f0a39e65796a1cc92d0a2ea729186ca5aca7a58)

The Mach-Zehnder transform is thus

![{\displaystyle {\begin{array}{rcl}U&=&BPB\\&=&{\frac {1}{2}}\left[{\begin{array}{cc}{1}&{-i}\\{-i}&{1}\end{array}}\right]\left[{\begin{array}{cc}{1}&{0}\\{0}&{e^{i\phi }}\end{array}}\right]\left[{\begin{array}{cc}{1}&{-i}\\{-i}&{1}\end{array}}\right]\\&=&-ie^{i\phi /2}\left[{\begin{array}{cc}{\sin(\phi /2)}&{\cos(\phi /2)}\\{\cos(\phi /2)}&{-\sin(\phi /2)}\end{array}}\right]\,.\end{array}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/4aff63aa7808a03191a5315b3f548834ce336f41)

The way we have defined these transformations here, the output modes

of the interferometer,  and

and  , are

, are

![{\displaystyle \left[{\begin{array}{c}{c}\\{d}\end{array}}\right]=U\left[{\begin{array}{c}{a}\\{b}\end{array}}\right]\,.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c9786a4cebe3997ae8ab2e2a99556bd27a67b002)

We are interested in the difference between the photon numbers

measured at the two outputs,  , where the

extra factor of two is introduced for convenience. We find

, where the

extra factor of two is introduced for convenience. We find

The measurement result  is thus

is thus

Define  , and

, and  . Recognizing that

. Recognizing that

is the difference in photon number between the two output arms,

and recalling that this is the main observable result from changing

is the difference in photon number between the two output arms,

and recalling that this is the main observable result from changing

, we identify the signal we wish to see as being

, we identify the signal we wish to see as being  .

.

Ideally,

the output signal should go as  . The signal due to

. The signal due to  goes

as

goes

as  , and we shall see that this is the noise on the signal.

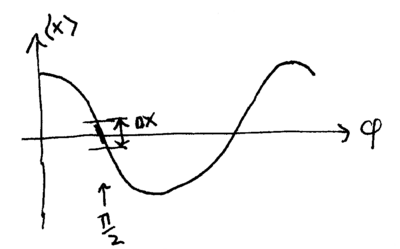

The average output signal

, and we shall see that this is the noise on the signal.

The average output signal  , as a function of

, as a function of  , looks like this:

, looks like this:

Note that if our goal is to maximize measurement sensitivity to

changes in  , then the best point to operate the interferometer

at is around

, then the best point to operate the interferometer

at is around  , since the slope

, since the slope  is largest

there. At this operating point, if the interferometer's inputs have

laser light coming into only one port, then the outputs have equal

intensity; thus, the interferometer is sometimes said to be

"balanced" when

is largest

there. At this operating point, if the interferometer's inputs have

laser light coming into only one port, then the outputs have equal

intensity; thus, the interferometer is sometimes said to be

"balanced" when  .

.

What is the uncertainty in our measurement of  , derived from the

observable

, derived from the

observable  ? By propagating uncertainties, this is

? By propagating uncertainties, this is

where

Let  , such that

, such that  , and

, and  .

.

Limit for coherent state input

For a coherent state input,  , we find

, we find

if we define  as the input state mean photon number.

Also,

as the input state mean photon number.

Also,

This is consitent with our intuition: the signal should go as  , and the undesired term goes as

, and the undesired term goes as  , so it is good that is small on

average. However, there are nontrivial fluctuations in

, so it is good that is small on

average. However, there are nontrivial fluctuations in  , because

, because

and  is nonzero for the

coherent state! Specifically, the noise in

is nonzero for the

coherent state! Specifically, the noise in  is

is

and thus the variance in the measurement result is

From Eq.(\ref{eq:l7-dphi}), it follows that the uncertainty in  is therefore

is therefore

This is a very reasonable result; as the number of photons used

increases, the accuracy with which  can be determined increases

with

can be determined increases

with  . The improvement arises because greater laser power

allows better distinction between the signals in

. The improvement arises because greater laser power

allows better distinction between the signals in  and

and  .

.

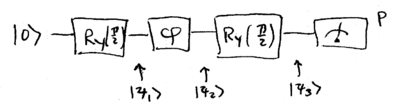

Limit for single photons

Another way to arrive at the same result, using single photons, gives

an alternate interpretation and different insight into the physics.

As we have seen previously, acting on the  ,

,  "dual-rail" photon state, a 50/50 beamsplitter performs a

"dual-rail" photon state, a 50/50 beamsplitter performs a

rotation, and a phase shifter performs a

rotation, and a phase shifter performs a  rotation. The Mach-Zehnder interferometer we're using can thus be

expressed as this transform on a single qubit:

rotation. The Mach-Zehnder interferometer we're using can thus be

expressed as this transform on a single qubit:

where the probability of measuring a single photon at the output is

. Walking through this optical circuit, the states are found to be

. Walking through this optical circuit, the states are found to be

such that

Repeating this  times (so that we use the same average number of

photons as in the coherent state case), we find that the standard

deviation in

times (so that we use the same average number of

photons as in the coherent state case), we find that the standard

deviation in  is

is

Given this, the uncertainty in  is

is

This is the same uncertainty as we obtained for the coherent state

input, but the physical origin is different. Now, we see the noise as

being due to statistical fluctuations of a Bernoulli point process,

one event at a time. The  noise thus comes from the amount

of time the signal is integrated over (assuming a constant rate of

photons). The noise is simply shot noise.

noise thus comes from the amount

of time the signal is integrated over (assuming a constant rate of

photons). The noise is simply shot noise.

Heisenberg limit: entanglement

The shot noise limit is not fundamental.

Here is a simple argument that something better should be possible.

Recall that the desired signal at the output of our Mach-Zehnder

interferometer is  , and the noise is

, and the noise is  .

If the inputs have

.

If the inputs have  and

and  , and if

, and if  were zero, then

the measured signal would be

were zero, then

the measured signal would be  . And at the balanced

operating point

. And at the balanced

operating point  ,

,

Thus, if the smallest photon number change resolvable is  ,

then

,

then  , from which it follows that

, from which it follows that

This is known as the "Heisenberg limit" on interferometry. There

are some general proofs in the literature that such a limit is the

best possible on interferometry. It governs more than just

measurements of phase shifters; gyroscopes, mass measurements, and

displacement measurements all use interferometers, and obey a

Heisenberg limit.

Heisenberg limited interferometry with entangled states

The argument above only outlines a sketch for why  might be an

achievable limt, versus

might be an

achievable limt, versus  ; it assumes that the noise

; it assumes that the noise  can be made zero, however, and does not provide a means for

accomplishing this in practice.

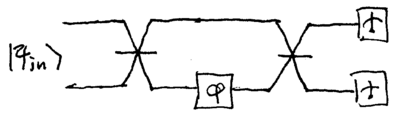

Many ways to reach the Heisenberg limit in interferometry are now

known. Given the basic structure of a Mach-Zehnder interferometer,

can be made zero, however, and does not provide a means for

accomplishing this in practice.

Many ways to reach the Heisenberg limit in interferometry are now

known. Given the basic structure of a Mach-Zehnder interferometer,

one can consider changing the input state  , changing the

beamsplitters, or changing the measurement.

, changing the

beamsplitters, or changing the measurement.

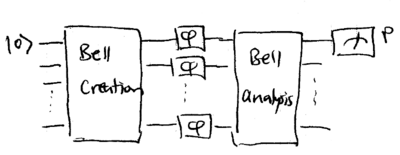

Common to all of these approaches is the use of entangled states. How

entanglement makes Heisenber-limited interferometry possible can be

demonstrated by the following setup. Let us replace the beamsplitters

in the Mach-Zehnder interferometer with entangling and dis-entangling

devices:

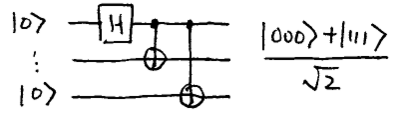

Conceptually, the unusual beamsplitters may be the nonlinear

Mach-Zehnder interferometers we discussed in Section~2.3. They may

also be described by simple quantum circuits, using the Hadamard and

controlled-{\sc not} gate; for two qubits, the circuit is

Note how the output is one of the Bell states. For three qubits, the

circuit is

This output state,  (suppressing normalization) is

known as a GHZ (Greenberger-Horne-Zeilinger) state. Straightforward

generalization leads to larger "Schrodinger cat" states

(suppressing normalization) is

known as a GHZ (Greenberger-Horne-Zeilinger) state. Straightforward

generalization leads to larger "Schrodinger cat" states

, using one Hadamard gate and

, using one Hadamard gate and  controlled-{\sc not} gates. Note that the reversed circuit

unentangles the cat states to produce computational basis states.

controlled-{\sc not} gates. Note that the reversed circuit

unentangles the cat states to produce computational basis states.

The important feature of such  -qubit cat states, for our purpose,

is how they are transformed by phase shifters. A single qubit

-qubit cat states, for our purpose,

is how they are transformed by phase shifters. A single qubit

becomes

becomes  . Similarly, two entangled

qubits in the state

. Similarly, two entangled

qubits in the state  , when sent through two phase

shifters, becomes

, when sent through two phase

shifters, becomes  , since the phases add. And

, since the phases add. And

qubits in the state

qubits in the state  sent through

sent through  phase shifters becomes

phase shifters becomes  .

.

When such a phase shifted state is un-entangled, using the reverse of

the entangling circuit, the  controlled-{\sc not} gates leave the

state

controlled-{\sc not} gates leave the

state ![{\displaystyle |00\cdots 0{\rangle }[|0\rangle +e^{ni\phi }|1\rangle ]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/6045fc2a6464b6cd42e9fb5c81084a169e808fda) , where the last

, where the last  qubits are left in

qubits are left in  , and the first qubit (the qubit used as the

control for the {\sc cnot} gates) is

, and the first qubit (the qubit used as the

control for the {\sc cnot} gates) is

Compare this state with that obtained from the single qubit

interferometer, Eq.(\ref{eq:l7-1qubitphase}); instead of a phase

, the qubit now carries the phase

, the qubit now carries the phase  . This means that the

probability

. This means that the

probability  of measuring a single photon at the output becomes

of measuring a single photon at the output becomes

The standard deviation, from repeating this experiment, on average,

would be

Using  , we obtain for the uncertainty in

, we obtain for the uncertainty in  ,

,

which meets the Heisenberg limit.

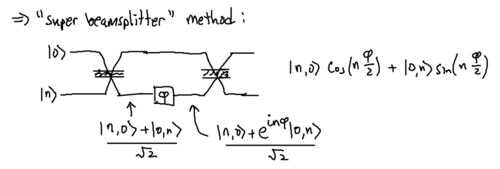

Heisenberg limited interferometry with "super beamsplitters"

Another way to reach the Heisenberg limit in an interferometer is with a different kind of beamsplitter. Suppose that instead of the usual beamsplitter, we have one which keeps  photon states together, such that an input

photon states together, such that an input  is transformed to

is transformed to

With such an interferometer, then, an interferometer made with two such beamsplitters:

will provide a phase shift  of angle proportional to

of angle proportional to  . The probability of measuring the output photon number to be zero is then

. The probability of measuring the output photon number to be zero is then

which gives, much as in the entangled photon interferometer case,

Combining this with

gives

The  states have been called "high noon" states in the literature. In practice, the degree of optical nonlinearity required to create such states is largely impractical at optical wavelengths, at realistic degrees of loss. However, one method for realizing a "super beamsplitter" close to that imagined here has been proposed, for microwave photons. See <refbase>789</refbase>, and references therein.

states have been called "high noon" states in the literature. In practice, the degree of optical nonlinearity required to create such states is largely impractical at optical wavelengths, at realistic degrees of loss. However, one method for realizing a "super beamsplitter" close to that imagined here has been proposed, for microwave photons. See <refbase>789</refbase>, and references therein.

Squeezed light interferometry

Heisenberg-limited interferometry can also be accomplished using a

variety of states of light, including squeezed states we studied earlier. Let us explore three configurations here.

Vacuum squeezed state input

Because squeezed states can move

noise between the  and

and  quadratures, it is intuitively

reasonable that a state with low phase noise could be used to provide

more accurate measurements of

quadratures, it is intuitively

reasonable that a state with low phase noise could be used to provide

more accurate measurements of  than is possible with a coherent

state, which has equal noise in the two quadratures.

than is possible with a coherent

state, which has equal noise in the two quadratures.

It might seem counter-intuitive, however, that we can get to the

Heisenberg limit by replacing not the coherent state input, but

rather, the vacuum state, in the Mach-Zehnder interferometer. This

works because at the balanced operating point, the noise in the output

is due to fluctuations entering in at the vacuum port. Before, we

used  as input. Let us now replace this by

as input. Let us now replace this by

where  is a squeezed vacuum state. Recall that for

the balanced interferometer, the final uncertainty in the phase

measurement is

is a squeezed vacuum state. Recall that for

the balanced interferometer, the final uncertainty in the phase

measurement is

where  , and

, and  . For the squeezed

vacuum + coherent state input, we find

. For the squeezed

vacuum + coherent state input, we find

Thus, the uncertainty in the phase measurement is approximately

In the limit of large squeezing, ie  , the squeezed

vacuum has nonzero average photon number,

, the squeezed

vacuum has nonzero average photon number,  , so this expression does not vanish to zero. Rather, there

is an optimal amount of squeezing, at which point the minimum phase

uncertainty goes as

, so this expression does not vanish to zero. Rather, there

is an optimal amount of squeezing, at which point the minimum phase

uncertainty goes as  , which is

close to the Heisenberg limit. See <refbase>184</refbase>

, which is

close to the Heisenberg limit. See <refbase>184</refbase>

Yurke state input.

The Heisenberg limit can also be reached

using the Mach-Zehnder interferometer by replacing the input light

states with this unusual squeezed state

![{\displaystyle |\psi _{in}\rangle ={\frac {1}{\sqrt {2}}}\left[{|n-1{\rangle }|n\rangle +|n{\rangle }|n-1\rangle }\right]\,.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/fddaf8eca4a41d65a799f1448a487eafc95e3022)

This is known as the Yurke state. It happens to be balanced

already, and thus instead of operating our interferometer at

, we operate it at

, we operate it at  , such that the output

measurement gives

, such that the output

measurement gives  , and

, and  , and the

final uncertainty in the phase measurement is

, and the

final uncertainty in the phase measurement is

For the Yurke state,

In calculating  , the terms with

, the terms with  drop out, leaving us with

drop out, leaving us with

Similarly, it is straightforward to show that

Thus, the uncertainty in  is

is

which is the Heisenberg limit.

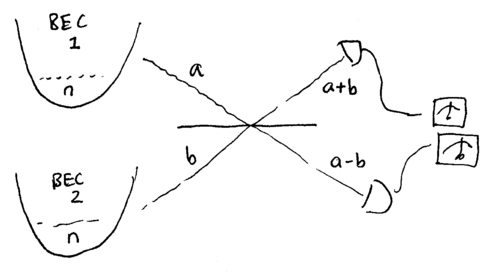

Yurke state: Experiment?

Given how useful the Yurke state could be for interferometry, it is

meaningful to consider how such a state might be made. One

interesting proposal starts with two Bose-Einstien condenstates,

prepared in a state of definite atom number, which we may model as two

number eigenstates  . The two condensates are weakly linked

through a tunnel, which we may model as a beamsplitter, and detectors

are placed to look for a single atom at the outputs. This is sketched

below:

. The two condensates are weakly linked

through a tunnel, which we may model as a beamsplitter, and detectors

are placed to look for a single atom at the outputs. This is sketched

below:

If the top detector clicks, then one atom has left the condensates;

however, it is unknown from which it came. The post-measurement

state, after this single click, is thus

written unnormalized. Normalized, the proper post-measurement state

is

This is the Yurke state. If the bottom detector had clicked instead,

we would have obtained  instead, which is also

useful.

instead, which is also

useful.

Similar techniques, involving beamsplitter mixed detection of

spontaneous emission, can be used to entangle atoms (as we shall see

later). More about this BEC entanglement method can be found in the

literature; see, for example, <refbase>185</refbase>

, for the proposal to create Yurke states;

<refbase>186</refbase>,

for an experiment in which a squeezed BEC state was generated, and

<refbase>187</refbase>, for a

proposal to do Heisenberg limited spectroscopy with BECs.

Sensitivity to loss

Entangled states, while very useful for a wide variety of tasks,

including interferometry and metrology, are unfortunately generally

very fragile. In particular, entangled photon states degrade

quickly with due to loss.

Consider, for example, the two-qubit state  (suppressing

normalization). If one of theses photons goes through a

mostly-transmitting beamsplitter, then the photon may be lost; let us

say this happens with probability

(suppressing

normalization). If one of theses photons goes through a

mostly-transmitting beamsplitter, then the photon may be lost; let us

say this happens with probability  . If a photon is lost,

the state collapses into one with one remaining photon, say

. If a photon is lost,

the state collapses into one with one remaining photon, say  .

This is a product state -- no longer entangled. It is not even a

superposition. No photon is lost with probability

.

This is a product state -- no longer entangled. It is not even a

superposition. No photon is lost with probability  .

Even worse, if both modes suffer potential loss of a photon, then

no matter which mode looses a photon, the entangled state collapses;

this happens even if just one photon is lost. Thus, the

state retains some entanglement only with probability

.

Even worse, if both modes suffer potential loss of a photon, then

no matter which mode looses a photon, the entangled state collapses;

this happens even if just one photon is lost. Thus, the

state retains some entanglement only with probability

.

And worst of all, if we have an

.

And worst of all, if we have an  -photon cat state

-photon cat state

, and all modes are subject to loss

, and all modes are subject to loss

, then useful entanglement is retained only with probability

, then useful entanglement is retained only with probability

. Due to such loss, the phase measurement uncertainty

of an entangled state interferometer will go as

. Due to such loss, the phase measurement uncertainty

of an entangled state interferometer will go as

which is clearly undesirable.

Some physical systems, however, naturally suffer very little loss, and

can keep entangled states intact for long times. Photons

unfortunately do not have that feature, but certain atomic states,

such as hyperfine transitions, can be very long lived. Thus, many of

the concepts derived in the context of quantum states of light,

actually turn out to be more useful when applied to quantum states of

matter.

Questions for thought

- Where does the random

and

and  noise come from, in standard interferometry and in Heisenberg-limited interferometry? Is it from (a) the input state, (b) the beamsplitters, (c) projection noise in the final measurement?

noise come from, in standard interferometry and in Heisenberg-limited interferometry? Is it from (a) the input state, (b) the beamsplitters, (c) projection noise in the final measurement?

References

- Squeezed light and multi-photon interferometry

- <refbase>5226</refbase>

- <refbase>5225</refbase>

- <refbase>5227</refbase>

- <refbase>5231</refbase>

- Entangled / multi-photon interferometry with Atoms and Ions:

- <refbase>5222</refbase>

- <refbase>5232</refbase>

![{\displaystyle B={\frac {1}{\sqrt {2}}}\left[{\begin{array}{cc}{1}&{-i}\\{-i}&{1}\end{array}}\right]\,.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/4e2d43ef535ef4f670f31b7ce4cfe7a15c1890f8)

![{\displaystyle [a,b]^{T}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/dcbe0f3bd3d712a823544cc4985e4dbd35b6967d)

![{\displaystyle {\frac {1}{\sqrt {2}}}\left[{\begin{array}{c}{a-ib}\\{b-ia}\end{array}}\right]=B\left[{\begin{array}{c}{a}\\{b}\end{array}}\right]\,.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/3bcdd91d0e9a05a80b3165137ecd92a63b40bc81)

![{\displaystyle P=\left[{\begin{array}{cc}{1}&{0}\\{0}&{e^{i\phi }}\end{array}}\right]\,.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/3f0a39e65796a1cc92d0a2ea729186ca5aca7a58)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{array}{rcl}U&=&BPB\\&=&{\frac {1}{2}}\left[{\begin{array}{cc}{1}&{-i}\\{-i}&{1}\end{array}}\right]\left[{\begin{array}{cc}{1}&{0}\\{0}&{e^{i\phi }}\end{array}}\right]\left[{\begin{array}{cc}{1}&{-i}\\{-i}&{1}\end{array}}\right]\\&=&-ie^{i\phi /2}\left[{\begin{array}{cc}{\sin(\phi /2)}&{\cos(\phi /2)}\\{\cos(\phi /2)}&{-\sin(\phi /2)}\end{array}}\right]\,.\end{array}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/4aff63aa7808a03191a5315b3f548834ce336f41)

![{\displaystyle \left[{\begin{array}{c}{c}\\{d}\end{array}}\right]=U\left[{\begin{array}{c}{a}\\{b}\end{array}}\right]\,.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c9786a4cebe3997ae8ab2e2a99556bd27a67b002)

![{\displaystyle |00\cdots 0{\rangle }[|0\rangle +e^{ni\phi }|1\rangle ]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/6045fc2a6464b6cd42e9fb5c81084a169e808fda)

![{\displaystyle |\psi _{in}\rangle ={\frac {1}{\sqrt {2}}}\left[{|n-1{\rangle }|n\rangle +|n{\rangle }|n-1\rangle }\right]\,.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/fddaf8eca4a41d65a799f1448a487eafc95e3022)